Luke Nicosia (’21) discusses the surprisingly sympathetic portrait of the Roman emperor Nero that emerges from a 2004 film by British Director Paul Cohen released on television in the Imperium series.

Nero is the second installation in the Imperium series; originally planned as a six-film series based on the history of the Roman empire, only five were produced (Winkler, 2017). According to Rave (2003), Nero began as a French enterprise, but due to a lack of interest and funding, Italian and German partners became involved in the project. The German company EOS Entertainment, as well as the Italian company Lux Vide, eventually took over the project (Crew United, “Imperium – Nero (2003)”). By Nero‘s release, eighty percent of the movie was funded, the additional twenty percent to be made up by sales (Rave, 2003). Nero featured actor participation from several countries, namely Britain, Italy, and Germany (Rodriguez, 2003). The production crew, likewise, also represented various European countries. The producer, for example, Jan Mojto was from Slovakia, the director Paul Marcus from Britain, and the assistant director, Fabrizio Castellani, Italian (Rave, 2003).

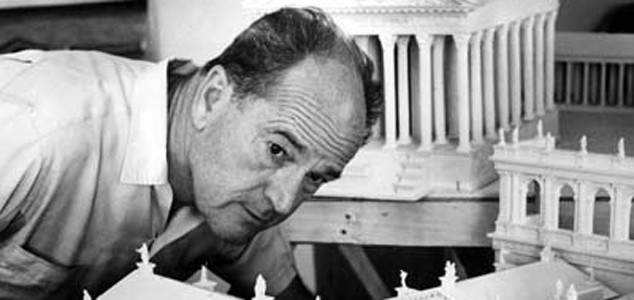

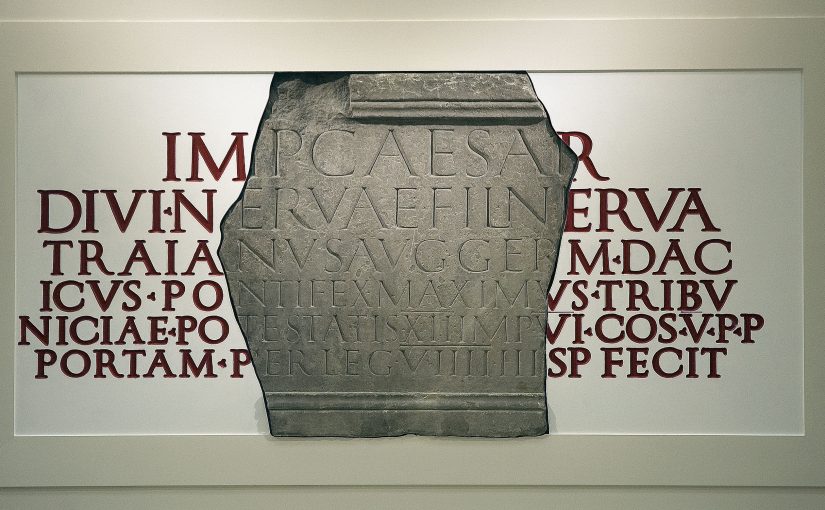

The five films had a budget of 125 million euros–roughly $190,000,000, adjusted for inflation (Rodriguez, 2003). For filming, a remote coastal town by the name of Hemmamet was chosen as a location; starting in 2002, all five movies were filmed there (Winkler, 2017; Rodriguez, 2003). For the interest of saving money, the five films used the same set. Constructed of polystyrene material, it cost 15 million euros alone, and spanned 22,500 square meters– or around 240,000 square feet (Rave, 2003). The buildings were based off ancient Roman structures, but scaled down 33 percent in size (Rave, 2003). I would think that while the set’s consistency shows continuity across the films, the set material design serves to save on construction costs. Filming for Nero began on December 20th, 2003, and ran for eight weeks (Crew United, “Imperium – Nero (2003)”). The film was then produced back to Italy (Winkler 2017). It was subsequently released later in 2004 as a television film (Winkler, 2017). Judging by the lack of scholarly information on the film, it likely did not have a large release.

Plot Synopsis

Nero (2004) begins with a young Nero (James Bentley), his father Domitius (uncredited) and mother Agrippina (Laura Morante) at their estate, located outside of Rome to avoid the wrath of the city’s “cruel master” Caligula (John Simm) (1:36). That night, Tigellinus (Mario Opinato), Caligula’s righthand man, breaks into their house with Praetorians, butchers Domitius in front of Agrippina and Nero (as he hides under his bed). Tigellinus spots the hiding Nero and takes him and Agrippina to Rome. At court, Caligula sadistically offers her a food platter with Domitius’ head on it. Distraught, Agrippina is pressured by Caligula, who holds a knife to Nero’s throat, to confess to taking part in a conspiracy against the emperor. Caligula then asks Porridus (Simón Andreu) and Septimus (Ian Richardson) for recommendations on how to punish her. When the answers they give are insufficient, he banishes Agrippina, and has Burrus (Maurizia Donadoni) escort Nero to his aunt Domitia’s (Ángela Molina) homestead.

At the estate, Nero quickly befriends the slave Apollonius (Philippe Caroit), a former actor, and his young daughter Acte (uncredited). Nero is unable to speak, traumatized by his father’s death. Yet, Apollonius coaxes him to talk by reciting Homer to him. Ten years later, Nero (Hans Matheson), going by “Lucius,” has grown fond of both the slave lifestyle as well as Acte (Rike Schmid). He professes his love to her, and they vow to get engaged. Apollonius forbids it, however, as it would break her heart to love someone of Patrician blood, who is forbidden to marry a freedwoman. In exile, meanwhile, Agrippina visits a soothsayer (Liz Smith), who reveals that Nero will become emperor, but at the price of Agrippina’s murder. Agrippina is left wondering who will kill her as the specter disappears.

In Rome, Caligula is assassinated by his guards at a brothel, and Claudius (Massimo Dapporto) is proclaimed as emperor. He is reluctant to take the throne, but on the urging of his wife Messalina (Sonia Aquino) he obliges. Nero and Acte are plotting to run away to Greece and become musicians, when Tigellinus arrives to bring Nero back to Rome. Wanting to make up for the injustices Nero and his mother–who was also recalled–suffered, Claudius offers anything Nero desires. On Nero’s behalf, Agrippina demands that Seneca (Matthias Habich) be brought back from exile and become his tutor. When Seneca arrives, Agrippina informs him that his duty is to make her son into the ideal emperor. Nero sneaks out that night, and takes Acte to the hills overlooking the city. There, he tells her that they will have to delay their departure plans, as his mother has told him she is in danger and requires Nero to be vigilant on her behalf. He tells her, however, that he plans to ask Claudius if he may be consul of Greece and take her with him.

Nero admits his love for Acte to Seneca, and when Agrippina overhears, she goes to Domitia’s residence and tells the slave she will be one of Nero’s concubines. Agrippina, however, tells Domitia that she must send her to Sardinia immediately. Acte, Apollonius, and Rufus (Marco Bonini), another slave, are on their way to Rome when Domitia’s overseer (uncredited) averts their carriage towards Sardinia. Acte protests this, and a fight between Apollonius and the slave-driver ensues. Apollonius is injured, but Rufus incapacitates the slave-driver. They go to the house of Etius (Jochen Horst), a family friend, where Apollonius later dies of his injuries. At Rome, Messalina sneaks out one night to marry another man. Agrippina, who had heard of Messalina’s odd night behavior, informs Claudius and his Praetorians, who put a stop the ceremony. On Claudius’ orders, Tigellinus kills both Messalina and her new husband. Claudius then marries Agrippina and adopts Nero as his son. To tie the family bond stronger, Claudius demands that Nero marry his daughter Octavia (Vittoria Puccini). Nero rejects the proposal, as he still loves Acte. Agrippina and Seneca, nevertheless force him to do it. After the ceremony, Nero abandons Octavia and runs off to Acte for the night. Octavia later commits suicide on hearing of their engagement.

When Claudius leaves for a military campaign in Brittania, Agrippina takes control of the empire. He returns a year later and sees that Agrippina has been printing her image on the coinage. He confronts her about this and tells her that he has changed his will to designate his epileptic son Britannicus (Francesco Venditti) as his heir. Nero, meanwhile, asks Claudius for the consulship of Greece, part of his plan to run away with Acte. Claudius grants it, but quickly thereafter dies from his poisoned food, perpetrated by Agrippina, who also takes his will. Nero tries to run away, but is caught by Seneca, Tigellinus, and Burrus, who declare him emperor. At first, Nero routinely visits Acte, who lives with Etius. When Octavia becomes upset with this and confronts him, Nero replies that he does not love her and demands that Octavia divorce him. She agrees, faking that she is impotent to get the marriage annulled; Nero subsequently gets engaged to Acte.

At a gladiatorial exhibition, Nero becomes upset with the bloodlust of the audience; responding to the audience’s cries for death, Nero proclaims the installation of the Nuronia, poetic competitions free from blood. At the Senate, Nero proposes that the empire cut taxes, which the Senate almost votes entirely against, which enrages Nero. Enraged, Nero kicks over the voting pots and says that he will implement the changes anyways. much to the dismay of his mother. His mother, dismayed by his actions, begin to plot against him. Tigellinus catches word of their plot and reports this to Nero, who banishes his mother from the palace. This angers his mom, who resorts to using Claudius’ will as leverage. Nero learns of his mother’s new plot and has Britannicus poisoned. Acte finds out his actions and leaves him, running away to her slave friend Claudia (Emanuela Garuccio), who lives with the Christian Paul of Tarsus (Pierre Vaneck).

Without Acte, Nero spirals. He first has his mother killed, feeling that she has made his life hell. Then, he falls in love with and marries the seductive Poppea (Elisa Tovati), who introduces him to hallucinogens and wild partying. When the Senate learns that, they will engage in mock gladiatorial combat at the wedding, Porridus and Septimus bring Burrus, Seneca, and Tigellinus into their conspiracy. After Tigellinus betrays them again and informs Nero, however, the Senators are murdered, and Seneca is forced to commit suicide. Acte, meanwhile, becomes baptized and becomes a Christian. After asking Domitia for forgiveness, she returns to see Rome burning. After the fire, Nero unveils his plans to rebuild Rome, including the Domus Aurea at its center. Some worry that it makes Nero look responsible for the fire, which leads Poppea and Tigellinus to suggest that they blame the Christians.

At a lyre performance of his, Nero accidentally falls on and kills the pregnant Poppea. He turns to Paul, captured by the Romans and known to perform healing miracles, to save her. Under the threat of death, Paul says he is unable to help her, and it is implied that Paul is later executed. Acte confronts Nero, begging to return to him and for him to spare the Christians. Nero refuses and sends her away, calling her a traitor. Then, when Galba usurps him, Nero barely escapes a traitorous Tigellinus, as well as a mob of Romans who throw rubbish at him. He goes to a river, tosses his diadem in, and slits his wrists. As he dies, Acte finds him, and he asks for her forgiveness, which she grants. Acte cremates his body, and as she lights the pyre, she tells the attendees to “forgive [Nero]” for his crimes (3:09:10).

Background Information According to Ancient Sources

The film Nero is based off the works of Cassius Dio, Suetonius, and Tacitus. The works which give the best account of Nero do not shy away from his faults, of course. Cassius Dio, a historian writing roughly 130 years after Nero’s lifetime, recounts the emperor in his larger anthology, Roman History. As a historian recounting Rome’s entire history, Dio is less specifically targeting Nero in his work, as is suspect with writers who lived contemporarily with the emperor. Dio’s primary intent is to systematically explain Nero’s rule and descent into madness as he does with others. His methodology has its basis on cause-and-effect, how each bad action is the result a prior event. Following the murder of Britannicus, for example, Dio states that “Seneca and Burrus no longer gave any careful attention to the public business [so that they may] preserve their lives. Consequently Nero now openly… proceeded to gratify all his desires” (LXI.7.5 Trans. Cary, 1961). To Dio, Nero’s reputation can be explained through the identification and analysis of such critical moments; it does not suffice him to say just simply if a ruler is bad or not, and an explanation as to why and how is necessary.

Suetonius’ account also comes from a larger work, The Lives of the Caesars. He takes great pleasure in recounting the vices of the emperors ranging from Julius Caesar to Domitian. Suetonius’ discussion on Nero is 57 chapters, one of his more extensive accounts. He attempts to sway the reader one way or the other, giving both the good and the bad. His account, however, is not balanced by any means. While the first nineteen sections deal primarily with Nero’s successes, the remainder discusses his vices and demise, as told through gossip-like anecdotes that pertain to Nero. He recounts, for example, how Nero “castrated the boy Sporus and actually tried to make a woman of him” (28 Trans. Rolfe, 1997). This story is referenced in Dio’s work as well, but it is not a significant point. Suetonius presents such stories not as historical facts, but as gossip that he makes use of to evaluate Nero.

Tacitus’ Annals is more focused on the military and legal matters affecting the empire. While he recounts military campaigns in Britannia and Armenia, Tacitus also spends time discussing accusations made in the Senate and the outcome of their trials. Tacitus is slightly less biased and opinionated than Suetonius; he will include rather damning stories of Nero and his mother, Agrippina, but attributes it to other writers. He has this to say, for example about Agrippina’s desire for the throne: “According to Cluvius’ account, Agrippina was so far driven by her desire to hold on to power that…she quite often appeared before her inebriated son all dressed up and ready for incestuous relations” (13.2, Trans. Barrett &Yardley, 2008). The story is surely revealing about Agrippina and Nero, yet because Tacitus cites it from the work of another, he does not appear to be a spreader of rumors as Suetonius does. Tacitus does not dwell on negative stories as much, only using such for historical purposes. In comparison to Dio’s work, the Annals function more as a collection of current events than a historiographical account; it is surely far, however, from being a collection of anecdotes, as is Suetonius’ style.

Dio’s narrative portrays Nero as interested in power from the beginning, suppressing his siblings and destroying Claudius’ will (61.2.3). When he acquired his power, it gave Nero the access he needed to make his fantasies a reality. Tacitus, however, blames Agrippina more sternly than the other texts. He says that Agrippina “had long been set on committing the crime, was quick to grasp the opportunity she was offered, and was not short of agents for it” (12.66 Trans. Barrett & Yardley, 2008). Tacitus then admits that in the earlier years of Nero’s reign, she executed dissidents on Nero’s behalf (13.1). Agrippina, therefore, is at fault for the misdeeds which occurred in the early years of Nero’s reign. Nero becomes more responsible for his crimes, however, when his mother, Seneca and Burrus lose influence over his behavior. Nero most closely resembles Tacitus’ rendition more than the other remaining two texts. The film, from the beginning of Nero’s ascension to the throne, Agrippina motivates and manipulates an unwilling Nero into becoming emperor. As Nero becomes more comfortable as a ruler, however, he relies less on his mother, and soon turns on her thereafter.

The film, however, heavily deviates from the ancient source material. Nero’s father, Domitius, is shown as a loving and caring father, but according to Suetonius, Domitius was “a man hateful in every walk of life” (6 Trans. Rolfe, 1997). Domitius did not seem to love his son either, saying that he and Agrippina were too evil to give birth to a noble child (6). He had died of dropsy, furthermore, instead of being murdered by Caligula, when Nero was three (6). According to the film, Nero is seven when he witnesses his father’s murder, subsequently spends ten years on Domitia’s farm, and finally takes the throne at seventeen. Much attention is also given as to how the family is depicted as close-knitted. Nero’s death, furthermore, did not occur at the side of a river, by slitting his wrists, or with Acte present. After being declared an enemy by the Senate, Nero committed suicide in the home of one of his freemen; when he failed die, his freedman helped finish the job (Suetonius, 49). The timing of events is altered to make Nero more pitiable, once an innocent boy who witnessed the brutal murder of his father, who later fell into darkness

The depiction of Nero’s beginning and end also helps to focus on Acte and Nero’s lifelong relationship. Acte was not as significant to the emperor’s life as Nero suggests. While Acte is seldom mentioned in the ancient sources, it is known that Nero did have a strong infatuation with her (Dio, 61.7.1). Yet, she is recurrent throughout Nero’s life, from his traumatized childhood to his death. Nero‘s romantic facet, in short, avoids commenting on the sexual controversies surrounding Nero. While the film portrays his libidinous relationship with Poppea, critics did not appreciate how Nero’s sexual proclivities were excluded (Gradyharp. “Another in the Series of Imperium – Nero’s Life Tidied Up A Lot). The emperor was accustomed to having more than one bedfellow as once, including Sporus, who he utilized for his own personal fantasies (Dio, 63.13.2). Stories such as these are excluded for two reasons: it blemishes Nero’s character, as well as that of the movie, beyond repair. The presence of Christian teachings and characters throughout the film suggest that Acte and Nero’s romance is portraying the ideal Christian relationship. While ancient sources do not comment on Acte’s faith, the movie chronicles her transformation into one. A film that has its basis in spreading Christian teachings, therefore, ought to avoid such sacrilegious topics.

Recurrent Themes and Analysis

Nero is striking in its portrayal of the emperor, as it breaks from all older conventions. Famous movies such as Quo Vadis? (1951) portray Nero as a pagan tyrant that trounces the morally superior Christianity (Blanshard & Shahabudin, 2011, p. 41). A film also worthy of note is the 1981 comedy History of the World, Part I, where Nero is described as a piggish glutton interested in dining and bathing in treasure (Cyrino, 2009, p. 204). These films draw more heavily on Nero’s vices, as described by ancient sources, and put it at the forefront of his character. Nero, however, humanizes him to an extent that other films do not. Nero first comes across as a misunderstood musician, who has the simple interests of running away to Greece with Acte (Dahm, 2009, p. 5). He has no interest in taking power at first and is forced onto the throne instead. He later succumbs to corruption, however, losing the innocence he was previously presented with having.

The contrast between Nero’s early and later years is but a struggle between good and evil, corruption and innocence, moral and immoral. Nero’s childhood, his “good” is made evident by his sympathetic portrayal. When Nero is sent to Domitia’s residence, he is not referred to as Nero, but as Lucius, “the bringer of light,” by Apollonius (15:26-15:36). The film takes Nero’s praenomen literally in this case, as throughout the film he is depicted as void of all vices. This depiction heavily contrasts with that of Tigellinus. As an assassin, he is always dressed in a dark black uniform throughout the film, giving the audience the impression that he is a sinister character and surely clashes against the “bringer of light.” Tigellinus, however, embodies evil in its purest form. His purpose, as exhibited throughout the film, is to murder on the orders of the emperor. His loyalty too is questionable, as he clearly has his own self-interests. While he is loyal to the emperor he serves, his loyalty only lasts until his own interests no longer ally with the interests of the emperor. He is complicit in the deaths of Caligula, Claudius, and eventually attempts to kill Nero himself, and in this way embodies the evilest nature of the empire.

With this good and evil contrast evident in the film, certain characters undergo a change from light to dark, or from “dark” to light. Agrippina, at first, is a simple loving mother, yet she ends up manipulating others into get her son to rule. Domitius’ murder serves as a critical changing point, as it spurs Agrippina’s need for security. She convinces Nero to forego his plans to run away to protect her from the “vipers” in Rome that threaten her life (42:59-43:30). Security, however, becomes skewed with the vision she receives while in exile. She first spies on and has Messalina killed for her infidelity, subsequently marrying Claudius; then, while Claudius is in Britain, she mints money of her own likeness; later, she instructs Seneca to shape her son Nero into the model emperor; and when Claudius changes his will to have Britannicus succeed him, she has him poisoned. Everything she does in this case is solely to get Nero onto the throne, yet her actions are immoral. The film attempts to portray Agrippina as having been corrupted through her good intentions. By wanting security, each action serves as a slippery slope to the next. Even when Nero is atop the throne, she continues to scheme.

Agrippina’s demise seems to reflect onto Nero as well. At first, Nero is against the bloodthirsty nature of Rome. At the gladiator games, for example, Nero is appalled by the audience’s call for the death of a gladiator (1:46:40-1:49:52). On his announcement of the Nuronia, which he wishes to be free of any bloodshed, Porridus comments that with the bloodless games, “he’s lost [the audience],” as they wish for blood. The contrast between Nero’s ideal empire and the state of the actual one is further contrasted when Nero proposes his first reform: tax cuts. When he proposes this idea to the Senate, however, a senator hysterically questions “you want to lower taxes?” (1:02:59-1:03:14). The line speaks for the nature of the Senators, therefore; by opposing what many audience members would view positively, the Senate becomes synonymous with selfish elites that care nothing for other people. It may also serve to comment on the ancient sources and explain their inherent bias against Nero. When the Senate votes almost unanimously against him, Nero oversteps then and institutes these changes anyways. This is the beginning of Nero’s fall from grace, as while he has good intentions, it does not reflect well on his character, just as his mother early on had good intentions which later became not so. Nero’s character shift is best summarized with his line to Acte: “Lucius to you, Nero to the world” (1:39:39). The child that was Lucius now grows thin, while the bureaucratic Nero grows stronger.

Acte serves as Nero’s moral compass throughout the movie, keeping “Lucius” around while “Nero” in check. He is increasingly pressured by others, however, to do immoral deeds. At Agrippina’s urging does Nero take the throne, yet when she begins to lose control of him, she turns on him. His taking of the throne is with good intentions, as he hopes to make a better world by ruling. His dream fails to become a reality, however, when he realizes that people plot against him. At Seneca’s urging, however, Nero has Britannicus killed to take away her leverage against him (2:04:40). Acte’s subsequent departure following learning of Nero’s crime only adds to his descent into madness. Without Acte, his moral compass, Nero’s character devolves into unbridled madness. He is seduced by the titillating seductress Poppea, who introduces him to powerful narcotics and unrestrained debauchery (2:30:30-2:31:09). The scene of Nero and Poppea’s marriage to her serves as a comparison to this shift, as while the scene is slow and festive, it is blurry, off-kilter, and bizarre, mimicking his drug-fueled escapade with Poppea in the prior scene (2:38:35-2:40:36). It flashes back and forth with the jovial wedding procession to the brutal murders of Septimus and Porridus. The contrast seems to indicate that Nero takes delight in the thought of death, best summarized by how he sadistically smiles when he tells Seneca to commit suicide (2:41:11). Nero, who had previously proclaimed to never shed blood for his namesake, has stooped to a point where he will kill as he pleases.

After departing from Nero, Acte too undergoes a character change, only this time her demeanor improves. When she learns of Nero’s murder of Britannicus, she runs away from the keep, leaving Nero and their engagement (2:15:00). Here, Acte is unable to forgive Nero for his misdeeds. He teaches her about the Christian teachings of forgiveness and piety, and ultimately motivates her to save a Nero “falling into darkness” (2:27:36). Having learned to accept the Christian ethic, Acte, dressed in humble rags just as she was with Nero when she was a working slave, approaches an ornately dressed Nero and asks to return to his life and that he spare the Christians. She is nonetheless unfazed when Nero simply admits to her that “I am lost” and sends her away (3:01:14). Acte’s transformation is more indicative on the moral of the film as a whole. Nero and Agrippina both find themselves in a pagan Rome that idolizes greed, bloodshed, and disloyalty. Being invested in this realm too long causes a character’s downfall. Yet Acte, who goes to Christianity, finds herself improved instead of corrupted. Even though she is wronged by Nero at the end, Acte reminds the audience in her final line about the Christian ethic: “let us forgive him, as we hope to be forgiven” (3:08:44-3:09:20). The moral superiority of the Christian faith, paired with the tale of Nero’s corruption, illustrates that Nero was not always terrible and deserves pity for his fate.

The film does not execute this moral well, however. While the set’s absence of technology and style–an obvious nod to earlier sword and sandal films–is praise-worthy, dialogue delivery in many instances ruined the immersion of the film. Agrippina’s first line to Domitius is worthy of note, as her dialogue seems flat and ingenuine (1:19). Such scenes took away from the overall effectiveness of the film. While some actors proved to be rather powerful in their portrayals– such as John Simm’s portrayal of the insane Caligula– the lackluster acting of others ruin some pivotal moments of the film. Britannicus (2:11:45) and Claudius’ (1:30:22) death scenes are accompanied by one member of the cast uttering “he is dead” in an emotionless tone, which I found to be detracting to the gravity of the situation. Emotional scenes such as these were poorly executed in the film.

With a run-time of nearly three hours, Nero is far too long; the length is avoidable, however, as certain scenes are purposelessly elongated. Scenes such as Nero and Agrippina’s reunion last too long and are absent of any meaningful or inventive dialogue (37:30-20:22). The scene is hallmarked by somber violin music while one or two characters shed tears. The effectiveness of this trope, however, is lessened by its frequency (Gotan girl, “Recommended for Madness and Intrigue but there’s a Sap Alert”). At least a dozen similar scenes occur in different parts of the film, and while the purpose is to obviously coax an emotional response from the audience, the repetition of the trope ultimately lessens its effectiveness. The overdramatization of a challenging film idea proved incredibly obnoxious. The film’s deviation from the standard treatment of Nero truly makes the film stand out. Yet, due to underperformance, repetitive dramatic clichés and drawn out romantic scenes, the movie is not effective in conveying Nero’s downfall.

Bibliography

Blanshard, A. J., & Shahabudin, K. (2011). Classics on Screen: ancient Greece and Rome on film. Bristol Classical Press.

Crew United. ”Imperium – Nero (2003).” Crew United | the Network of the German-speaking Television and Film Industry. 2003. Accessed March 30, 2018.

Cyrino, M. S. (2009). Big Screen Rome. John Wiley & Sons.

Dahm, M. K. (2009). Performing Nero. Didaskalia, 7(2). 1-12.

Dio, Cassius; C., Cary, E., & Foster, H. B. (1914). Dio’s Roman History, with an English Translation. (Vol. 8) Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press; London: W. Heinemann, 1961.

Gotan girl. “Recommended for Madness and Intrigue but there’s a Sap Alert” Review of Nero (2005). Amazon.com, October 21, 2010. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/gp/customer-reviews/R1TJFJ1IVQ0J4N?ASIN=B000A1OFZ0

Gradyharp. “Another in the Series of Imperium – Nero’s Life Tidied Up A Lot.” Review of Imperium: Nero. IMDb, September 11, 2005.

Moldyoldie. “As the Empire Turns” Review of Nero (2005). Amazon.com, February 21, 2006.

Pauly, A. F., Evers, K., Eck, W., & Walter, E. (2006). Nero. In H. Cancik, H. Schneider, & M. Landfester (Eds.) & F. G. Gentry & C. Salazar (Trans.), Brills New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

Rave, C. (2003). 25,000 Square Meters Rome in Hammamet. (H. Matheson, Trans.) Deutsche Presse-Agentur. Retrieved from https://www.hansmatheson.org/25000-square-meters-rome.html

Rodriguez, M. (2003). Telecinco Rolls in Tunisia ‘Imperium’, the Biggest Production in the History of T.V. (H. Matheson, Trans.). Television- Life and Leisure. Retrieved from https://www.hansmatheson.org/telecino-rolls-in-tunisia—madrid.html

Suetonius; Bradley, K. R., & Rolfe, J. C. (1914). Lives of the Caesars. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014. Retrieved from Loeb Classical Library.

Tacitus; C., Barrett, A., & Yardley, J. (2008). The Annals: The Reigns of Tiberius, Claudius, and Nero. Oxford: OUP Oxford. Retrieved from eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) database.

Winkler, M. M. (2017). Classical Literature on Screen: Affinities of Imagination. Cambridge University Press. 300-312.