Haydon Alexander (’24) argues that the relative quickness of Ovid’s hexameter lines is a key aspect of his style.

Towards the end of his life, Ovid wrote letters to friends in Rome describing the misery of his exile on the frontier of the empire in what is now Romania. In a letter addressed to Cornelius Severus Ovid considers the reasons why he no longer gets any enjoyment out of writing poety (Epistulae ex Ponto 4.2.33–34):

or because composing a poem with no one to recite it to

is just the same as dancing [lit. “making rhythmical gestures”] in the dark.

sive quod in tenebris numerosos ponere gestus,

quodque legas nulli scribere carmen, idem est.

Ovid doesn’t mean that he is sad that his poems aren’t being read (in fact, his exilic poetry was sent to Rome and was read). Rather, he sees his writing as joyless without a live audience to spur him on. The way Ovid describes dancing (“making rhythmical gestures”) is significant, since numerosus can refer to both rhythmical movements of the body and rhythmical speech, and Ovid himself in a famous passage uses the word numerus to mean “poetic meter” (Amores 1.1.1). Ovid’s letter from exile gets at the joy of performing Ovid’s work live, and one of the principal reasons for this is because of Ovid’s deep mastery of meter. The importance of meter is easily lost when we read silently, so to that end, we will explore below some of the special qualities of Ovid’s metrics, and the way in which he discusses meter directly in his work.

In his surviving corpus Ovid wrote in only two meters . In the Metamorphoses, the nominally epic poem which describes the history of the world told in myth, he wrote in dactylic hexameter, in which each line has six feet of either a long and two short syllables (a dactyl) or two long syllables (a spondee). This is the meter of Homer, Hesiod, and Vergil, among other writers of epic poems, and it is first discussed critically by Aristotle, who considers it to be the proper meter of epic poetry (Poetics 1459b. See Morgan 2000: 99–120, esp. 99-100). For a more in-depth look at how the meter looks in practice with visuals and video accompaniment, look here and here.

Perhaps his most famous (in infamous) work, the Ars Amatoria, “The Art of Love,” a supposedly didactic but also highly unserious set of poems on seduction, was composed, like the rest of his works apart from the Metamorphoses, in elegiac couplets: lines are in pairs, the first of which is metrically identical to a dactylic hexameter, and the second of which is a dactylic pentameter, i.e., a hexameter line with five rather than six feet (See Claasen 1989 and Herr 1937). This is a meter which was also pioneered by Ancient Greeks, and was commonly used for love poetry in the first century B.C. Rome by Catullus, Tibullus, Propertius, and Ovid himself. The ways in which Ovid uses meter in tandem with a vast array of poetic devices is the subject of many complete books, so we will focus here on some of the most distinguishing ways that Ovid plays with meter, and also some of the unique flair that come from his metrical self-awareness in his own writing.

Ovid is often self-referential and metaliterary. At the start of the Amores, Ovid’s poetic collection depicting a love affair with a woman he calls Corinna, he argues with Cupid concerning his meter (Amores 1.1.–2 trans. Slavitt 2011):

Arms and the violent deeds of men fighting in battle …

Those are the noble subjects I would address

in the grave meters suited to grave matters, but no,

Cupid appeared to trim my lines by a foot.

Arma gravi numero violentaque bella parabam

edere, materia conveniente modis.

par erat inferior versus—risisse Cupido

dicitur atque unum surripuisse pedem.

In the first place, he puns on the meter, writing that Cupid steals his “foot,” referencing the fact that the elegiac couplet has one fewer foot than the equivalent 2 lines of dactylic hexameter. But more than this, it is clear that he gives particular weight to the thought of meter, opening the work with the “grave meter” he is talking about is dactylic hexameter. Conversely, he calls his elegiac couplets “Rather more informal, playful even–despite my serious aims” (nec mihi materia est numeris levioribus apta, 1.19–20 trans Slavitt). He writes as if he is trapped by his metrical choice. Of course, he makes that choice himself, but this is an instance where Ovid is close to talking to his audience about how important meter is to him.

So, Ovid uses meter as a shortcut to let his reader know what to expect, and he uses the history of both his meters to prime his readers for what his works will contain. Indeed, the Amores all deal with love, and as he promises, not in a particularly serious way. Ovid writes a ridiculous scene (1.6) that has him lying outside the door of his love, begging the doorman to let him in. Another reads like a limerick about “an over-the-hill playgirl” (1.8).

In the Metamorphoses, Ovid plays around with expectation. Because the work is written in hexameters, we are asked to consider it an epic. However, it skirts many of the “rules” to which earlier epics adhere. Most obviously, it does not have a unified narrative in the way that the works of Homer or others have. Moreover, Ovid does not adhere to his own statement in the Amores about “grave meters,” because like the rest of his works, Ovid is often deeply unserious in tone. An example is when he tells the story of how Tiresias is blinded in a short story that talks about Jupiter and Juno arguing about who gets more pleasure from sex (3.316–38). This is hardly the stuff of grand stories, but it is in Ovid’s “epic.”

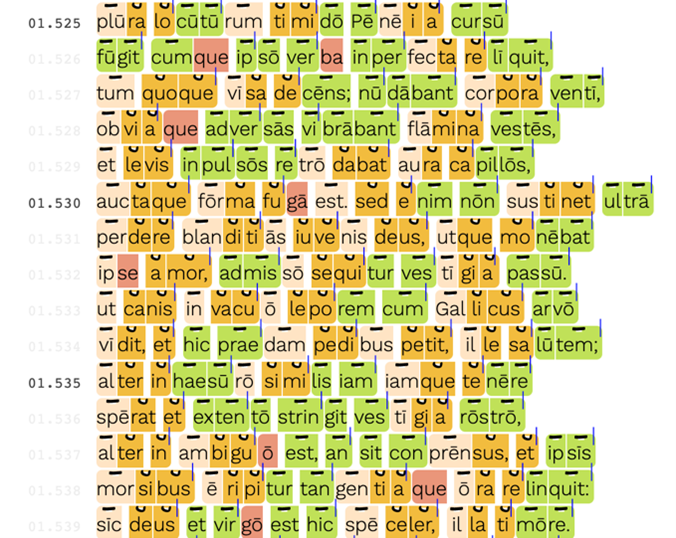

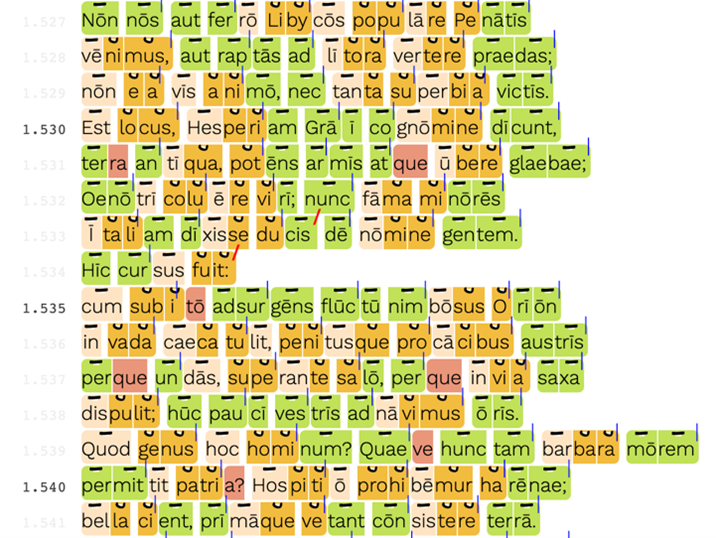

Metrically, Ovid’s epic differs from that of his slightly earlier contemporary, Vergil. Metrical analysis shows that Vergil’s Aeneid is relatively dominated by spondees, the feet which have two long syllables. This means that his work encourages the speaker to slow down and to luxuriously take in each line. The Metamorphoses has more dactylic lines, with many feet consisting of a long followed by two short syllables (see Ben Johnson’s online tutorials on the metrical composition of Ovid and of Vergil; and Herr 1937: 5). This results in a poem which gallops along relatively quickly, contrasted with Vergil’s statelier pace. One of many illustrative instances is when he tells of Apollo’s chase of Daphne (Met. 1.525-39). During the lead up to the chase, as Apollo realizes that his words will not convince her to be with him, the lines move slowly, but as the chase commences and reaches its climax, the lines become more dactylic, making the poetry move faster and faster. This is one instance where Ovid uses speed to evoke the content of his verse. This results in a tone which matches the tenor of Ovid’s writing which is opposed (though neither superior or inferior) to Vergil: where Vergil feels grand and momentous, Ovid does something else: his writing is foremost pure, unadulterated entertainment that moves. A visualization of a typical passage in which spondees are coded green (courtesy of the website Hypotactic) shows the extent of the tendencies.

But it is not merely in the Metamorphoses where Ovid is uniquely dactylic. In a study of the elegiac couplets of Ovid, Propertius, and Tibullus, Maurice Platnauer (1951: 36–37) found that the line type with four dactyls (the most “galloping” line) occurs 6.7% of the time in Ovid’s elegiac work, more than three times as often as that of Tibullus and over five times as often as in Propertius (see Greenberg 1987). Conversely, lines with four spondees (the type of line which most encourages slowing down) are far less likely to occur in Ovid, about five time less likely than in Tibullus and more than eight times less likely than in Propertius. So, it is not only in the Metamorphoses that Ovid uses the mechanics of meter in ways different from his contemporaries and those who came before him.

Why did Ovid make his poetry move more quickly than that of his contemporaries? Why, when he says his opinion on what hexameters should be in his early works, does he contradict himself when he writes without the “epic grandeur” (Jones 2007: 10–11) for which he himself advocates? Does he actually believe in a “proper” meter for each type of poetry? And indeed, why is he self-referential about him poems in his own work? Peter Jones (2007: 11–15) suggests that Ovid is keenly aware that he shouldn’t (and probably can’t) recreate the spark of his epic predecessors when he writes the Metamorphoses, and that this is what inspires him to write such a unique epic. Applying this insight to meter, we can see why Ovid was so intentional and unique about meter. He attempts to modernize the poetic form by removing what he perhaps saw as the dust and stuffiness from Vergil and providing something modern and entertaining in a new way. He might get at the entertainment from mere subject matter, but as the saying goes, “it’s all in the delivery.” By galloping along through his poetry, Ovid brings new life into old stories in the Metamorphoses, and similarly, he brings new levity to much of the scenes of his elegiac works, and through self-reference, he almost begs his audience to notice the difference. Moreover, where Vergil and other predecessors focus on the epic, yet inherently distant and even somewhat sanitized, grand old scenes to elicit reactions from his audience, Ovid takes all the little absurd scenes and jolts his audience through them, making them feel a range of emotions: a range which can only occur to full effect with the speed and inevitability of a live poem, sung in its unique galloping meter.

Meter is just one of the things that make Ovid’s poetry unique, but it is reasonable to suspect that it might have been the thing that Ovid thought most unique about his work. Thus, in a moment in his later poems which reads in a “sad clown” sort of way, he puns on his meter by saying (Tristia 1.15-6):

Go, book, and greet places dear with my words:

I will touch them with what ‘foot’ I may.

vade, liber, verbisque meis loca grata saluta:

contingam certe quo licet illa pede”

He goes on to ask forgiveness if his work is not as good for his not being in Rome to write and present it (1.35–49). Even towards the end of his life, he is still self-conscious and self-referential concerning meter. He seems to think that in exile he has lost control of his work because he cannot express himself in meter. So, unlike the modern argument that meter constrains poetry, for Ovid, meter is essential to the character of his work. Without his intense attention towards and self-awareness of his meter, the unique attitude which Ovid achieves in his work would lack its enduring strength.

References

Claasen, Jo-Marie. 1989. “Meter and Emotion in Ovid’s Exilic Poetry,” Classical World 82.5: 351–365.

Greenberg Nathan A. 1987. “Metrics of the Elegiac Couplet,” Classical World 80.4: 233-41.

Herr, Margaret Whilldin. 1937. “The Additional Short Syllables in Ovid,” Language 13.2: 5–31

Jones, Peter. 2007. Reading Ovid: Stories from the Metamorphoses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morgan, Llwellyn. 2000. “Metre Matters: Some Higher-Level Metrical Play in Latin Poetry,” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society, 2000.6: 99–120.

Platnauer, Maurice. 1951. Latin Elegiac Verse: A Study of the Metrical Usages of Tibullus, Propertius and Ovid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Slavitt David R. 2011. Love Poems, Letters, and Remedies of Ovid. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.