Rachel Pistol (Dickinson ’25) looks at two modern re-tellings of the Odyssey from Penelope’s point of view, Milica Paranosic’s opera Penelope and the Geese (2019) and Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad (2005) and finds that, despite their differences, both acknowledge the complexities of womanhood more effectively than Homer’s original.

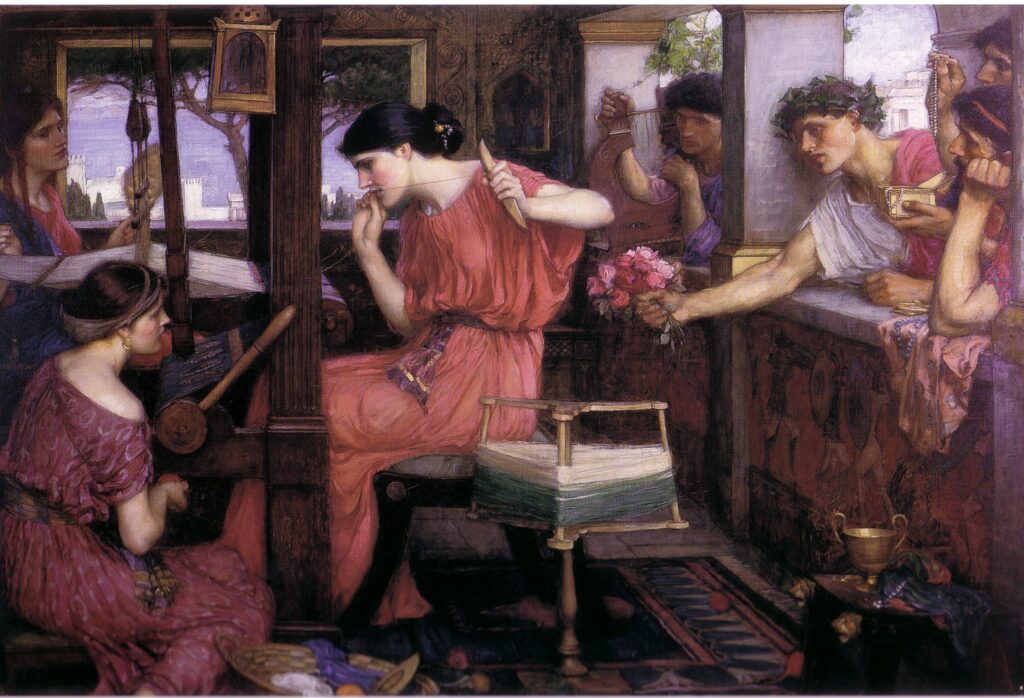

In the Odyssey, Penelope is depicted as having several positive qualities, chief among them being her fidelity to her husband, her wit, and her intelligence. However, we as readers see just a glimpse of what she endured during the twenty years that Odysseus was away, and even this is mostly focused on the few years that she was being courted by the suitors. All three of these qualities are shown in the myth through her constant despair over Odysseus’ absence and how she never explicitly accepts any of the suitors’ courtships, trying to delay this through weaving and unweaving Laertes’ burial shroud. However, whether she remained entirely chaste during this time later became a topic of ambiguity (Su 2010). Another significant point in Penelope’s story is her dream in which twenty geese whom she loves are killed by an eagle before the eagle reveals that this dream is a vision, with the geese being the suitors and the eagle being Odysseus (Homer Odyssey 19.540–554). This throws into question why Penelope was distraught over the death of the suitors in her dream, and whether that meant that the geese were not really the suitors but a representation of something else (Levaniouk 2011). Both plot points are integral in Penelope and the Geese and The Penelopiad, two modern works that take their inspiration from Penelope’s story and are both told primarily from Penelope’s point of view. This shift in perspective gives new meaning to these central events, although they are taken in different directions.

Penelope and the Geese is an opera by Cheri Magid told almost entirely from Penelope’s point of view as she reminisces on her time away from Odysseus right before seeing him again. In these twenty years, she has taken many lovers, both male and female, and has taken a lock of hair from each lover to weave into a blanket. Throughout the piece, Penelope debates where to put a lock of hair from Odysseus, leading her to recall several of her lovers and what she learned or how she benefitted from her encounters. At the end of the opera, Penelope is anguished over whether Odysseus will accept that her infidelity does not diminish her love for her husband, nor how much she has missed him over the years. The story ends with Penelope saying “Odysseus, I have something to tell you” (Paranosic 2019 1:09:36) leaving the audience to wonder whether she ultimately decides to tell Odysseus the truth or if she is going to tell him the same stories that the original Penelope in The Odyssey did.

This tale of Penelope’s encounters with the suitors serves to place Penelope and Odysseus on equal pedestals. In The Odyssey, Odysseus has relations with Calypso and Circe, yet it is well established that his goal is to return home to his beloved wife (Homer Odyssey 5.204–224). Rather than frame Penelope as a strictly loyal wife awaiting Odysseus’ return, she also has lovers and, just like her husband, this does not minimize how much she has missed him or her love for him over the period he has been gone. With Penelope being well known in both the ancient myth and modern times for her fidelity, this retelling of the story raises the question of whether this Penelope should still be considered a faithful wife. While Odysseus is not popularly described as a faithful husband, readers of The Odyssey cannot deny his loyalty to Penelope, and I believe the same can be said for Penelope in Penelope and the Geese, especially as Penelope voices very similar thoughts to Odysseus that yearn for a reunification of the couple. The opera manages to take Penelope’s drastically different experiences and, in allowing the audience to hear Penelope’s side of the story, still draws parallels between her and her husband, reaffirming their commitment to each other, even if it is unconventional.

The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood also tells the events of The Odyssey from Penelope’s perspective, although the similarities between the novella and the opera do not extend far beyond that. Throughout the story, Penelope compares herself repeatedly to Helen, first jealously and later haughtily. Helen serves as Penelope’s foil. Where Helen is beautiful, Penelope is plain; where Helen had many men fighting to marry her specifically, Penelope saw the men fighting to marry her as more concerned with the dowry; where Helen is proud of how many people died because of her and her beauty, Penelope wants to live a quiet life with her husband. While Penelope is compared to Clytemnestra in The Odyssey to highlight her fidelity to her husband, Atwood’s version of Penelope compares herself to Helen to highlight how she might be plain in looks but is great in spirit and mind. This focus of who Penelope is as a person rather than who she is as a wife only becomes clear once Penelope is in control of telling her own story, and depicts the strength that Penelope had throughout the trials she had to endure in the events of The Odyssey.

Like Helen, Penelope does admit that she enjoyed the attention from the suitors, mostly because she found it amusing. She also tells the readers that she occasionally daydreamed about which one she would want to bring to bed, even though she never slept with nor wanted to marry any of the suitors because she did not like them. Beyond simply ignoring or rejecting the suitors, however, Penelope encourages them to continue trying to win her over simply to keep them appeased lest they try to win Penelope by force. This perspective, untold by the original myth, sheds light on how Penelope had to carefully tread the line between encouragement and avoidance with the suitors, and how dangerous she felt the situation was. This is a feeling that many women both in antiquity and today would likely resonate with, and one that is likely only portrayed because Atwood is able to utilize her own experiences and better portray womanhood than the male-centered narrative of The Odyssey.

Another point in which Penelope and the Geese and The Penelopiad diverge concerns Penelope’s dream and its meaning in the larger narrative. In the opera, Penelope dreams of the geese just as she does in the original myth, but her distress is better explained in the context of her various relations with the suitors. Since the opera dedicates much of its time establishing the care that Penelope has for each of the suitors, it makes more sense in this perspective why she is upset at their deaths. In the opera, Penelope sings that she is glad to be engulfed by the geese’s feathers because it means that she is no longer lonely (Paranosic 2019 58:30), further emphasizing her connection to the geese and the suitors they represent. She also draws parallels between the geese’s hearts and her heart, eventually using the phrase “our heart” (ibid 1:00:25), making them seem as one, just as she has done in weaving the suitors’ hair together in her blanket. By allowing Penelope to tell her own story, including her encounters with the suitors, to the audience, we can better empathize with her distress as we know that Odysseus killing the suitors would also be destroying the people who helped Penelope to grow and be happy over the course of her husband’s absence.

As The Penelopiad removes the ambiguity that Penelope has slept with or even cared for the suitors, it makes her dream even more confounding for the audience, until we get to hear of it from this Penelope’s perspective. Since Penelope knew that Odysseus was himself, even in disguise, she actively chose to tell him about her dream as a test (Atwood 2005). Odysseus interpreted the dream in the same way he did in the original myth, but Penelope tells the audience that he was wrong. She narrates that the geese were not the suitors but rather her twelve maids, which is why she was so distraught over their deaths. Throughout the time that Odysseus was away, Penelope developed a strong bond with her twelve youngest maids as they helped her unravel Laertes’ burial shroud every night. They develop inside jokes with each other and grow even closer when many of the maids are raped by the suitors in an effort to get closer with them to gain information. Even when some of the maids ended up falling in love with the suitors, they still relayed information back to Penelope, so she knew what to expect from them, showing their loyalty to her. This makes their death in the novella even more heartbreaking, especially as Penelope blames herself since she kept the maids’ involvement in her schemes a secret to protect them. In allowing Penelope to tell her own story, including the role of the maids and their real motivations behind their actions, it makes their death, already a glossed over event in the original myth, mean more both to Penelope and the wider theme in The Penelopiad of double standards of justice between the genders.

Both Penelope and the Geese and The Penelopiad expand on the events in The Odyssey by utilizing Penelope as a narrator. Through this, both pieces clear up ambiguity in the narrative, although they each take this in different directions. However, both pieces do depict Penelope as a more complicated character, who is put on an equal pedestal with Odysseus in both love and cleverness. This creates a more well-rounded narrative that also acknowledges the complexities of womanhood, especially in the time of the original Odyssey.

Bibliography

Atwood, Margaret. The Penelopiad. New York: Grove Press, 2005.

Levaniouk, Olga. Eve of the Festival: Making Myth in Odyssey 19. Hellenic Studies Series 46. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies, 2011.

Paranosic, Milica. Penelope and the Geese. Saugerties, 2019.

Paranosic, Milica. “Penelope and the Geese by Milica Paranosic and Cheri Magid.” August 14, 2019. Performance, 1:38:27.

Su, M. “Penelope.” In The Classical Tradition, edited by Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most, and Salvatore Settis, 1st ed. Harvard University Press, 2010.

Wilson, E., trans., Homer: The Odyssey. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2018.