Cicero did not equate disability with incapability, argues Samantha Ritschel (’26).

I have lived life as a disabled person for over a decade. I was not born disabled. My disease, Friedreich’s Ataxia, began affecting me when I was eleven. So many doors that were previously open for me, suddenly shut, and I needed to find a new path forward. For me, that path led me to the world of the Classics. Classical Studies renewed something in me; it gave me a purpose, and with purpose comes the drive to succeed.

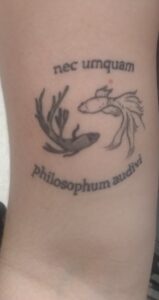

Throughout my academic career, ancient philosophers have occupied a great deal of the subject matter of my studies. I hate philosophy. I have never listened to a philosopher, and quite frankly, I don’t think I ever will. My experiences and the way I must live my life due to my disability cannot be mapped on to the philosophies that I am taught. Call me a pessimist if you must, but I prefer the term realist. To know oneself is the best thing that someone can do for themself, and for me that means accepting limitations and carving a path for myself, even though it will never be easy. And sometimes, to know yourself, you have to make a statement.

There is debate among the disabled community about disability first language and its use to refer to someone. I respect the opinions of others, but let me make mine clear. To use the language “person with a disability” erases who you are at your core. I am a disabled person. There is no taking the disability out of me. I am aware of the fact that when people meet me for the first time, the first thing they see is my wheelchair; they see the wheelchair rather than the person on the initial meeting. I am not saying that disability is what makes you who you are, I am saying that disability is part of you, whether you like it or not. There is no sense in chaining yourself with self-doubt and concern about how others may perceive you. I’m not saying that you are not allowed to be anxious, worried, or angry at the fact that you are not considered a typical person. But it is important to not let that consume you. Life is about the experiences that you have and the path that you forge for yourself. As a disabled person, I needed to forge a realistic path. I am aware how inconsistent I sound. Is this not philosophy? Is my thought process not the same type of doctrine that I despise? And you would be right, I am many things, and self-aware is one of them. This type of philosophy, one in which disability does not equate to incapability, is one that I hold close to my heart.

As I said earlier, I have learned to love the Classics, especially the Latin language. It is from this love of the Classics that I found an idea for my research project: the treatment of the disabled in ancient Rome. My original thought was to research physical disability in Rome, but I realized that it was too broad. I decided to research the treatment of the blind in Rome. I did this partly because of my father and partly because of my love of the Latin poet, Catullus. My dad runs a company that researches gene therapy for blindness caused by rare genetic diseases, Atsena. This, in combination with a few poems written by Catullus that state a variation of “I love you more than my own eyes,” led to this project. I would like to take a moment to acknowledge and appreciate Jason Morris (Dickinson ’00), who helped me throughout this project. If not for him, I would have never thought to look at the treatment of blind individuals in Rome from a philosophical perspective. I hate philosophy because it cannot be mapped on exactly to my life as a disabled person, therefore it never occurred to me, that perhaps a philosopher in antiquity tackled the issue of disability. Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations tackles philosophy from a Stoic point of view, which is interesting, but the most interesting content can be found in Book 5. Book 5 provides examples and analysis of how disability not only does not equate to incapability but also does not affect one’s ability to live a happy and virtuous life.

Book 5 teaches that virtue itself is sufficient for living happily (as Cicero himself summarizes it in De divinatione 2.2, docet enim ad beate vivendum virtutem se ipsa esse contentam). Cicero is firm during his defense of virtue as the key to happiness (Barney, 16). Virtue in Rome has multiple facets; it does not have a singular definition meaning that virtue is subjective to an individual’s experience. This is evident in the Latin language. The word for virtue is virtus which has a myriad of definitions. The main definitions of virtus are manliness and courage. Typically, virtue is defined in terms of one’s strength, specifically their physical strength. Most of the time virtus is used to describe manliness or warrior-like courage. However, virtue cannot be defined as just physical characteristics. If virtus refers to manliness, then does that make a person virtuous? The third definition for virtus is more ethical. Virtue can be based on the character of an individual. A virtuous person, someone who embodies virtus is courageous in both spirit and fortitude. A virtuous man can be judged on his manliness and battle, but it is the goodness of his spirit, and his relentless drive to improve himself that makes him worthy of the word. In terms of the disabled population in Rome, virtus could not be achieved via manliness or battle-based courage. For them, virtus was based on the goodness of their character, and the courage it took them to advocate for themselves and become a functioning member of society. The blind in Rome demonstrated courage daily by existing in an inaccessible world and attempting to lead the life of a happy man. The Disputations, specifically book five, teach that an individual has nothing to fear as long as they pursue a virtuous life by facing the challenges of life courageously (Barney, 13).

Cicero had a unique perspective regarding the blind. He argues it is the soul which receives the objects we see (animus accipit quae videmus, 5.111). His point is that a blind man sees through his soul, not his eyes, which implies that the lack of vision does not determine an individual’s capability to enrich his soul, which would metaphorically enrich his vision. He clarified this further by stating “Now the soul may have delight in many different ways, even without the use of sight; for I am speaking of an educated and instructed man with whom life is thought; and the thought of the wise man scarcely ever calls in the support of the eyes to aid his researches” (ibid.).

The use of animus is as interesting as his argument. The definition of animus can be interpreted as soul, mind, or spirit. It can be translated any of these three ways, meaning that Cicero made a choice to use such an ambiguous term to speak about blindness. The use of such an ambiguous term implies that Cicero wanted his readers to decide which definition fits best. He speaks of the education and pursuit of knowledge that blind man is capable of. In this context, the translation of animus as “mind” rather than “spirit” or “soul” is more relevant. However, the impact of translating animus as soul or spirit makes for a stronger statement. If a blind man is still able to enrich his soul and manipulate his spirit through the ways of philosophy and education, then perhaps they are not meant to be ridiculed in society as they were typically. Furthermore, an individual who was blind is still able to be virtuous utilizing their animus to fortify their virtus. A blind man’s soul can be enriched with courage from their mental fortitude and spiritual strength rather than a body capable of typical Roman virtus (manliness). This argument is uniquely Cicero’s, as most of Roman society typically found no use for disabled individuals.

The Stoic Diodotus, who was blind, lived for many years at my house. Now whilst—a thing scarcely credible—he occupied himself with philosophical study even far more untiringly than he did previously, and played upon the harp in the fashion of the Pythagoreans, and had books read aloud to him by night and day, in the study of which he had no need of eyes, he also did what seems scarcely possible without eyesight, he went on teaching geometry, giving his pupils verbal directions from and to what point to draw each line. (Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 5.113)

The language used in this section of Book 5 is extremely positive; there are no obvious negative connotations. The tone of the passage is not only admiring Diodotus but makes sure not to diminish his value simply because he is blind. Cicero emphasized his learnedness by claiming that he kept himself occupied with the study of philosophy and the study of music, both of which are seen as signs of a learned Roman. He also included a mention of his ability to teach geometry to students. That is pertinent, as it signifies that Diodotus not only had a strong education, but also that his patrons consisted of elite Romans. This is clear because, primarily, the elite and wealthy Romans were able to afford classes on theoretical mathematics such as geometry (Asper, 108).

Although his emphasis on learning clarifies the type of man Cicero admired, what is more interesting is how he discusses disability. The approach to blindness is clear: with reasonable accommodation, a blind man has no need for his eyes. Cicero wrote explicitly that Diodotus did not require vision as long as someone read to him during his personal time for study. He also stated that as a teacher, Diodotus was able to give instructions verbally to his students. Therefore, he was still capable of teaching without needing to have his eyesight. Using Diodotus as an example, Cicero argued that educated blind men are capable of not only participating in Roman society but also thriving.

The typical attitude toward blindness and any disability in Rome is reminiscent of how today disability is treated. There were extreme restrictions on career opportunities for blind Roman citizens. Furthermore, there were many jokes made at their expense. Luckily, the Romans were not Christian at this time otherwise, like me, a random lady would pull out a rosary at a grocery store and start praying at them in pity. The prevalence of pity and uncomfortableness with disability has not changed from antiquity to now. However, Cicero was a breath of fresh air that I hadn’t ever considered before. I have read many of his works, but his philosophical work related to disability gave me some hope for philosophy in general. He believed that blind individuals were just as capable as those who could see. Cicero did not ridicule nor demean disabled individuals. In fact, he admired them for having the strength and resolve to do something with their lives. Cicero uses Diodotus, the blind Stoic, as an example of how disability did not equate to incapability; if accommodations were provided, a disabled the individual was just as capable as any other Roman.

References

Asper, M. 2009. “The two cultures of mathematics in ancient Greece.” In E. Robson, and J. Stedall (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Mathematics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barney, R. 2025. “The Aims and Argument of the Tusculan Disputations,” in Brittain, Charles, James Warren, eds., Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.