By Joelle Cicak

The 2009 Spanish film, Agora, directed by Alejandro Amenábar, is a historical drama that follows the religious upheaval of 4th century AD Alexandria and the life of the female philosopher, Hypatia (Rachel Weisz). This film examines the issue of fanaticized religion and preaches ideas of moderation, as well as the ability to question beliefs instead of blindly or stubbornly following preconceived ideas in a way that still rings poignant to viewers today.

Plot Outline

The movie Agora, follows the studies of the philosopher and mathematician, Hypatia as she attempts to understand the way that the planets, or “wanderers” as she calls them, move across the sky. Throughout the film she tests different theories, moving from the Ptolemaic system, which is Earth-centric and employs the use of epicycles, to the Aristarchus model, which is Heliocentric. In her studies, she is nagged by the wavering light of the planets as she tries to resolve how they orbit in a circle, which is in her opinion the most perfect shape. She is only able to reconcile this issue hours before her death when she realizes that the planets instead move in an ellipse.

In her dedication to her studies she spurns the love of her student, Orestes (Oscar Isaacs), by presenting him with a bloody menstrual napkin after he declares his love for her; she is also oblivious to the lust that her slave, Davus (Max Minghella) holds for her. A faithful follower of the Neoplatonist school of thought, she refuses to engage in the tumult that is caused by the clashes between pagans and Christians in Alexandria, invoking Euclid’s first law when she sees her students Orestes and Synesius (Rupert Evans) bickering over faith. Even when the pagans are called to attack the Christians, she forbids her students from fighting and continues to hold discussions after the pagans are barricaded inside the fortress-like temple of Serapis.

The only time Hypatia loses her temper is when the Roman emperor issues a decree that the Christians can dispose of the Library and Serapeum as they see fit, as punishment for the pagans’ transgressions. While she frantically collects books from the library before the Christians break through the gates, she screams at Davus, telling him that he is a useless slave. This incident causes Davus to leave her and assist the Christians in their destruction. Eventually he joins the parabalani, a group of black-robed Christian police led by Ammonius (Ashraf Barhom). These men mock the teachings of Hypatia and other such ideas of learning; they teach Davus not to question the acts of God.

With the destruction of the Serapeum and the outlawing of paganism, things only get worse. The Christians, under the leadership of Bishop Cyril (Sami Samir), turn a hateful eye to the Jews of Alexandria, attacking them during their Sabbath. Orestes, now Christian and a prefect, is powerless to subdue the hatred between the Christians and Jews; retaliation is inevitable. The Jews fight back, luring Christians into a church and stoning many of them to death. In response, Cyril calls for the death of the Jews, including women and children. Both Hypatia and Orestes try to calm the anger of the court, but they are unsuccessful and an emigration of Jews occurs as Synesius, now the Bishop of Cyrene, reenters the city.

Cyril, distrustful of Hypatia and hateful of her relationship with Orestes and Synesius, delivers a sermon in the old library, now converted into a church. In his sermon, he cites a passage from the Bible that women should always be submissive to men; he condemns Hypatia publicly, and tells all to kneel before the word of God. Orestes refuses and leaves under a hail of stones thrown by Ammonius, who is later executed for this action. Synesius comes to him later and derides him for his transgressions against God, causing Orestes to break down, apologizing to God, but stating that he could never condemn Hypatia.

Meanwhile, the parabalani join by Cyril in mourning Ammonius. Cyril declares Ammonius a saint and a martyr, whipping his brethren into anger; after he leaves, they begin to plot against Orestes, knowing that they can hurt him deeply by killing Hypatia. The next morning, Davus runs to warn her of their intentions, but in vain. They find her soon after she finishes a meeting with Orestes and Synesius, who tried and failed to convince her to be baptized into the Christian faith. With Davus following, she is dragged to the old Library and stripped of her clothes. As the parabalani collect stones, Davus suffocates her and leaves. His black robed brethren mutilate her body.

Historical Background

While none of Hypatia’s works survive, there are a few that focus on her. These include multiple letters sent to her by her student Synesius (later Bishop of Cyrene), Socrates Scholasticus’s Ecclesiastical History, Damascius’s Life of Isidorus, and the Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu —the only source to condemn Hypatia. The text that has the most to say on Hypatia is Damascius’ Life of Isidorus, chapter 43. Here, he describes Hypatia’s character with overwhelming praise. He states that she was not content with mathematics, but also studied philosophy, publicly lecturing on the works of Plato and Aristotle (Damascius, Isodorus 43A). He also states that she outdid her father in her intellect. Damascius goes on to describe her as virtuous, prudent, and just (ibid. 43A). These are all characteristics that drive her character throughout the movie, allowing Rachel Weisz’s portrayal to evoke an extreme empathy in the viewer.

Damascius, a Neoplatonist himself, had obvious reasons for praising Hypatia and for portraying her in this light. Neoplatonist philosophies were based on the ability to form constructions from an abstract idea, such as mathematics or beauty (Deakin 2007, 35-6). Since their world was one of ideas, with the concrete world as perceived through the senses coming in second, Hypatia’s ability to shun the material desires of humanity were extremely praiseworthy (ibid. 36). Damascius expounds this idea through the anecdote of Hypatia presenting one of her students with a cloth soiled in menstrual blood to abate his affections (Damascius 43A).

Hypatia’s Neoplatonist viewpoints would have contributed to her interest in mathematics, for mathematics is the most studied form of the abstraction mentioned earlier (Deakin 2007, 36). These studies also take on a religious aspect, for Neoplatonism contains religious elements not unlike Christianity (Deakin 2007, 80). Neoplatonist thought contains the idea of a “One” who is also “identified with the Good” and the means of finding union with the “One” are part of their studies in abstraction, which means separating themselves from the material world (ibid. 37). This realization makes sense of Synesius’s continued adoration of Hypatia throughout his life, even though he was a Christian (ibid. 84). The movie also makes a clever play at her beliefs when she responds that she believes in philosophy when she is accused of believing in nothing at all (1:24:28-1:24:39). Taken out of context, this line implies atheist views. However, with the knowledge of Plato’s philosophies and Neoplatonist beliefs, it simply shows that her beliefs differ slightly from that of the Christians.

The movie Agora uses primary source accounts such as this description of Hypatia, as well as political incidents and other events as a strong back bone, building the plot around it. The writers also use any holes or ambiguities in the sources to their advantage. For example, they recast the youth in Damascius’s anecdote about Hypatia and the menstrual cloth as Orestes, whose attempts to woo her fail throughout multiple scenes. There is significant evidence to show that Hypatia and Orestes had a close relationship, so much so that it is mentioned in the Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu. John states that Hypatia had gained Orestes’s support by “beguiling” him (Chronicle of John LXXXIV, 100). The knowledge of this account, although it was slanderous, creates an easy step for the filmmakers to combine the figure of Orestes and the youth. Furthermore, this combination is a means for the filmmakers to heighten the drama between Cyril and Orestes, as Cyril starts to make moves to condemn the woman who Orestes has loved for years.

Another area of ambiguity that the filmmakers use to their advantage is the absence of knowledge around Hypatia’s studies. The Suda states that she published three commentaries, one on Diophantus, one on astronomy, and one on Apollonian Conics (Suidas, Hypatia). This, and her aforementioned studies of philosophy and mathematics, is the extent of the knowledge about her work that has come down to us. Because of this lack of knowledge, the filmmakers take Hypatia’s studies to a symbolic level as she is shown trying to prove the existence of an orderly and peaceful cosmos in the midst of constant turmoil and bloodshed. The fact that we know her father, Theon, was the last president of the Museum of Alexandria—an institution of higher learning—also adds a symbolic nature to their relationship and the idea of the loss of knowledge via religious turmoil (Deakin 1994, 234). Such symbolism takes form as Hypatia is killed by Christians mere hours after her groundbreaking discovery in the shell of the library her father once tended. This hints that not only knowledge has been stripped from the Earth, but the means by which to acquire it has also been lost.

Although the film received strong backlash for its portrayal of Christians as violent and unintelligent, we can see again that the ancient sources are there to back this up. Almost all of the incidents of violence in Agora, whether incited by Christians, Jews, or Hellenes, can be found in multiple places. The violent acts of a group of black cloaked monks are also written about, which did, in fact include a man named Ammonius who attacked Orestes with a stone after accusing him of being a pagan and was later executed for it (Kaplow 2006, 12). Another accurate example of this religious anger is the destruction of the Serapeum, which the filmmakers mix with the Library, using Theon’s timeline to their advantage once more. According to the information available to us, after a riot that caused the death of many Christians, the Hellenes barred themselves in the Serapeum, only to flee from it when the Emperor declared the Christians could destroy it (Kapalow 20006, 10). It can also be seen through these sources that although no party was innocent, the Christians almost always were the ones to incite the violence and were usually victorious when the bloodshed ended, something that the movie makes very explicit (Kapalow 2006, 22).

Agora also accurately shows how each of these violent clashes incited the next, causing a cycle of murder and bloodshed that began with the destruction of the Serapeum, included clashes between the Christians and the Jews, and ultimately ended in Hypatia’s death (Kapalow 2006, 1). There is much debate among scholars, however, as to whether Cyril was the one who called for Hypatia’s death. Damascius states that Cyril had Hypatia killed out of jealousy for her popularity (Damascius 43E). While this statement tends to highlight his Neoplatonist beliefs and contrast Hypatia’s virtues with Cyril’s villainy, other sources agree; for instance, the Chronicle of John praises Cyril for disposing of her (Chronicle of John LXXXIV, 103). But modern scholars, such as J. M. Rist, say that Cyril’s involvement would be unlikely (Rist 1965, 222). Rist says in his translation of the Suda, that those who killed Hypatia were monks (ibid. 222). We do know that after Ammonius was executed, Cyril spoke his eulogy, and proclaimed him a martyr, as he did in the movie (Kaplow 2006, 12). This act was a direct means of undermining Orestes and could have incited the other monks to violence, due to Orestes close ties with Hypatia (ibid. 12). The Chronicle of John—like the parabalani in the film as they dragged her up the stairs into the library—states that Hypatia was a corrupting figure, saying that she dealt in magic and used her satanic wiles to gain followers (Chronicle of John LXXXIV, 87). Although this crescendo of violence seems too dramatic to be true, enough sources and accounts exist to show that the filmmakers of Agora definitely did their research.

Making the Movie

As can be seen by the obvious effort to research the historical context of 4th century Alexandria, Amenábar took great pains to create a believable movie that would transport the viewer back in time (Olsen 2010). He called it archaeology and said that it was a great feeling whenever they found something real to add to the script (“TIFF Alejandro Amenábar AGORA Movie Interview” 2010, 5:18-5:25). For example, he showed the crew images of late Roman Egyptian tomb portraits, proclaiming that they were reference photographs, or “the Bible” because of their level of realism, a theme that the movie pushed forth (5:25-5:46). Amenábar also stated that he wanted to show viewers as much as possible, the long streets, the architecture, the lighthouse, to truly envelop them in this world (2:50-3:14). He used giant sets and practical camera effects so that the characters had to move and react to a real space even though such effects would have been easier and cheaper to fabricate with computer generation (Olsen 2010). For example, when the Christians are destroying the Library, the camera pans upwards, over the dome, and then backwards, upside down (52:06-54:48). He also employed the use of impressive aerial shots to show the chaos on the streets, causing the Christians (who are cloaked in black) to look like an army of ants, running books out of the library to the fire pits to be burned (54:48-55:06). Because Amenábar felt that the actors had to physically interact with the space to give convincing performances, his crew constructed massive sets, employed thousands of extras, and shot the movie in the arid climate of Malta (Olsen 2010). Because of this, the movie took on the classic sword and sandal adventure style. The difference, however, lies in what Agora is actually about. For, as Olsen states, it contradicts the tropes of its genre; it is not only an action adventure, it is a movie about ideas. Amenábar states, “the real heroes in the movie are not the ones who use their swords, but the ones who use their minds” (Olsen 2010).

Rachel Weisz elaborated on this aspect of the film by discussing her portrayal of Hypatia and her views of the making of Agora. She stated that “even though it’s about ideas, what I wanted to portray was passion [. . .] I didn’t want her to be cold. There’s no love story, her love affair is with her work. To show passion for ideas, it’s definitely challenging” (Olsen 2010). Amenábar chose Weisz to play the part for the very same reasons, stating that she is “incredibly smart [. . .] so honest, so passionate (“TIFF” 2010, 2:11-2:21). Weisz said that what drew her to Agora was the naturalism in the acting and the realism of the film. She said that this is a film about today; it deals with contemporary issues of religious violence and the clash of religion and science (“Rachel Weisz Exclusive Interview for the movie Agora” 2013, 1:15-1:40). Amenábar related that the reason for the large camera pan outs that he creates to show the sounds of the Earth and the sounds of humans was to show that we sound no different today than we did then. We are still nasty and cruel to each other when faced with opposition (“TIFF” 2010, 3:50-4:12).

Max Minghella also spoke on the creation and portrayal of his character, Davus. Davus was a completely fabricated character, created to act as eyes for the audience and a bridge between the idealism of Hypatia—who represented intellectualism—and the aggressive faith of Ammonius, who represented the pervasiveness of the Christians (“Entrevista a Max Minghella y Oscar Isaac por Agora” 2009 2:45). Amenábar discussed how Davus is desperately in love with his mistress, Hypatia, and only learns astronomy because he wants to show her that he can be as smart as her other students (“Max Minghella – Behind the Scenes of Agora” 2013, 0:16-0:24).

Minghella stated that part of his job in acting this character was to figure out how much of his studies were because of his lust as opposed to his interest in learning (0:29-0:41). Hypatia’s flaw, however, is that she could never see Davus as an equal, as seen when she screams at him in the Library, stating that slaves are never around when one needs them (48:37-48:54). Davus’ realization of this flaw is a major part of his decision to become a Christian. In contrast to her beliefs on this matter, Ammonius teaches Davus that the Christian God views and embraces all His followers as equal, regardless of social standing (“Max Minghella” 2013, 1:40-1:53). Rachel Weisz explained that the point of the bath scene was to show that Hypatia barely even acknowledges Davus is a man, since she leaves the tub completely unabashedly to be dried by the slaves, including Davus. This is recalled at the end when her clothes are ripped off by the parabalani and she is shown completely vulnerable and afraid (“Rachel Weisz” 2013, 3:39-3:50). Such conflict of social views creates another interesting dynamic to the already complex movie.

Themes and Interpretations

Although Amenábar and the cast talk openly about their experiences and the creation of the film, there is a lot left unsaid. While Amenábar mentions that this film is about today and hints about its views on religion, he leaves out the fact that there is a very obvious tilt toward the ideas of Islamic extremism. The evidence lies in the casting. While the Hellenes’ pale skin and posh British accents are not unusual in a sword and sandal film, Ammonius and Cyril’s Arabic intonation become immediately obvious. Both actors, who are Israeli and Egyptian respectively, play the most extreme and violent characters in the movie (“Ashraf Barhom”; “Sammi Samir”). They incite chaos in multiple scenes and seek to undermine the ideals of learning and scholarship which Hypatia and her followers hold dear. It is important to note that the Christians in the film who respect Hypatia and her interests, such as Synesius and Davus, speak with the same British lilt as the Hellenes. That being said, I argue the casting and accent decisions were made in attempt to make this movie relevant to issues that are pressing the world today, much in the same way as the large pan outs. Contrary to the beliefs of many angry Christians who oppose this movie on the basis that Amenábar, an atheist, created Agora to push an atheist agenda, this movie instead acts as a cautionary tale for anyone who believe that there is no compromise for their ideologies (Mark 2014, 1).

If one looks closely at each character, it is easy to see that none of them are without flaws. Hypatia is as unwilling to compromise her beliefs as Ammonius, to the point that the two characters act as foils for one another. They exist as opposites in this movie and seek to portray the two extremes of opposing beliefs; both are doomed to be martyred for their strict ideologies. Ammonius who is led by impulse, righteousness, and revenge, relies on his faith in God to guide him through a bond which is so strong that he claims that God speaks to him “so quickly” that he has to ask Him to slow down. (1:21:00-1:21:13). Hypatia, led by reason and logic, talks many times of allowing bygones to be bygones for fear of a self-perpetuating circle of violence. Hypatia is, for the most part, unaffected by the turmoil in the streets, looking down on high from the balcony of her fortress-like house where she conducts most of her research. Although she speaks in court about the issues plaguing the city, she does nothing to help those around her and searches constantly for proof of a perfect cosmos, even though there is evidence all around her that this is not the case. However, unlike Ammonius and his chatty God, Hypatia is constantly vexed by the mysteries that the wanderers are hiding from her.

Ammonius, however, lives on the streets, willing to jump to the occasion when the alarm rises for a fire. When he is feeding the poor, he teaches Davus that money is nothing when one can help those around him. Ammonius also shows him how to have faith in powers beyond his control and welcomes him like a brother into his band of monks. Davus learned the opposite from Hypatia, who taught him to constantly question his beliefs, but was never able to treat him as an equal. Such opposing idealism creates a rift that cannot be bridged. Though they never interact, they are connected through Davus who is able to see both characters’ fatal flaws as the movie progresses. Like Davus, the viewer needs to realize that neither of these ideologies are without flaws and the inability to compromise is what leads to each characters’ ultimate destruction.

In fact, the character who is most willing to take a moderate view on his beliefs is Orestes, who embodies thoughtful and questioning views throughout the movie. For example, he allows Hypatia to spurn his love without retaliation and states when the Serapeum is under siege that he might as well find a new religion (40:54-41:02). He also refuses to take the gospel as law, as seen when he refuses to bow, and only acknowledges his insult to God when Synesius comes to him later to discuss Cyril. In this scene, his outpouring of emotion and anguish shows that he is a devoted follower of the Christian faith, regardless of his transgression earlier that day. However, unlike the other characters in the film, he is unwilling to compromise his personal convictions for a greater idea, whether it may be philosophy or religion. Instead, he disappears after Hypatia’s death, something that the movie uses as a means to illustrate that he is unwilling to bend to Cyril’s will any longer.

For her part, Hypatia refuses to compromise her ideologies of Neoplatonism to the point where she dismisses the guards who are willing to escort her home at the end of the movie. This decision ultimately leads to her death. Instead of pushing an atheist agenda, Amenábar is pushing one of moderation. We live in a world that contains many opposing viewpoints, but in the end, Euclid’s first law rings true and there are more things that “unite us than divide us” (14:56).

The idea of power overruling moderation and reason is another compelling theme in this film. There are many points in the movie where Orestes tries to put in place moderate edicts and laws that are soon negated by the threats of violence made by Cyril and his followers. Similarly, Hypatia’s use of reasoning in court never seeks to incite any change, as she has no real power and no followers. Because those who value reason and moderation are unable to control the more violent, more extreme forces at play, injustices occur. These injustices result in the exile of the Jews from Alexandria, as Cyril calls for the death of women and children, something that Orestes cannot publicly oppose without the danger of the Christian half of the city rising against him. The strength of these violent forces only seeks to empower people like Ammonius, who claims that his actions are God’s will (1:22:22-1:22:27). Such powers force all of the dignitaries to be baptized in public in the end. When Hypatia opposes this, and Orestes tries to persuade her by saying that he cannot fight this battle against Cyril alone, Hypatia states that if her only means of surviving is to become a Christian, then “Cyril has already won”, perfectly summing up the main issue at play in the movie (1:51:57-1:52:06).

Conclusion

The movie Agora attempts and, I believe, achieves its goal of causing viewers to think critically about the belief set they follow, whether it be a philosophy, political party, or religion. Amenábar uses actual historical accounts of this time period to portray a theme that continues to repeat itself throughout thousands of years of human history. He shows with an impartial eye that all parties are guilty of blind faith in some capacity, which causes many of the characters’ ultimate destruction. In the end, he points a finger at the viewer, cautioning us to live a life of moderation, for otherwise only violence and ignorance can ensue.

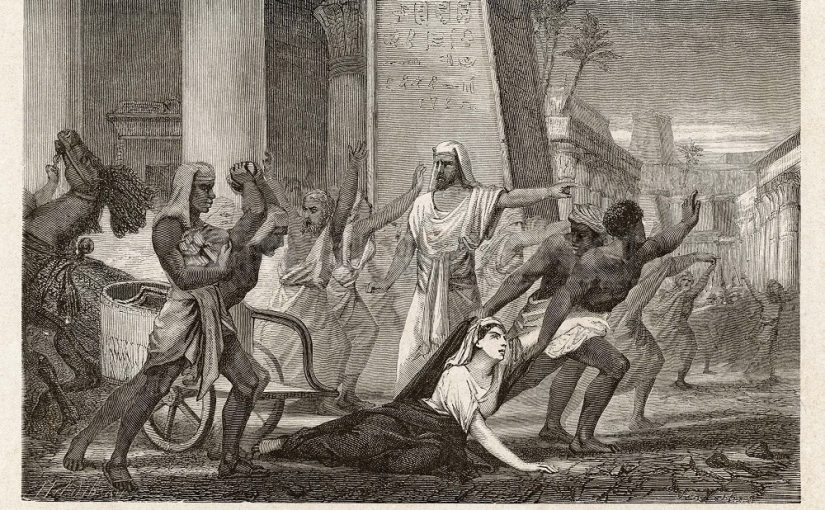

(Header Image: “Death of the philosopher Hypatia, in Alexandria,” by Louis Figuier. Published in Vies des savants illustres, depuis l’antiquité jusqu’au dix-neuvième siècle, 1866. Public Domain {{PD-1996}})

Work Cited

Agora. Directed by Alejandro Amenábar. 2009. Santa Monica, CA: Lionsgate, 2010. DVD. IMDb.com.

“TIFF Alejandro Amenabar AGORA Movie Interview.” YouTube video, 8:13. June 4, 2010.

Damascius. The Philosophical History. Ed. and trans. Polymnia Athanassiadi. Athens: Apamea Cultural Association, 1999.

Deakin, Michael A. B. Hypatia of Alexandria: Mathematician and Martyr. Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2007.

—. “Hypatia and Her Mathematics.” The American Mathematical Monthly 101.3 (1994): 234-243.

“Entrevista a Max Minghella y Oscar Isaac por Agora.” Youtube video, 3:50. Oct. 14, 2009.

John of Nikiu. The Chronicle of John, Coptic Bishop of Nikiu: Being a History of Egypt Before and During the Arab Conquest. Trans. Herman Zotenberg. Amsterdam: APA – Philo Press, 1850.

Kaplow, Lauren. “Religious and Intercommunal Violence in Alexandria in the 4th and 5th centuries CE.” Hirundo: The McGill Journal of Classical Studies 4. 2-26 (2005-2006): 1-26.

Mark, Joshua J. “Historical Accuracy in the Film Agora.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. February 17, 2014.

Olsen, Mark. “Indie Focus: In ‘Agora,’ a faceoff between faith and science.” Los Angeles Times, May 30, 2010.

Rist, J. M. “Hypatia.” Phoenix 19.3 (1965): 214-225.

“Sami Samir.” IMDb.com.

Suidas. “ Suidae Lexicon.” Trans. A. Adler. In Hypatia of Alexandria: Mathematician and Martyr, edited by Michael A. B. Deakin, 137-139. Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2007.

TheCinemaSource. Rachel Weisz Exclusive Interview for the movie Agora. Youtube video, 4:14. June 6, 2013.

“Max Minghella – Behind the Scenes of Agora.” Youtube video, 2:32. June 11, 2011.

Hollywood and History is an on-going series featuring the original work of students in the course Ancient Worlds on Film. Papers have been slightly edited for publication.