By Maeve Hogel

With the glaciers continuing to melt, the sea levels continuing to rise and extreme weather events getting more extreme, the pressure is on to make something big happen in climate change negotiations. However, every country has a different point of view on what that something big should be. The hopes of the low lying islands would be drastically different than the hopes of a developed country such as the United States. With the widely different views and goals of the many different Parties involved, a “top-down” approach on mitigation is not the best option, but when combined with a “bottom-up” approach to create a multi-track one, there may be hope for pleasing everyone while doing what is best for the planet.

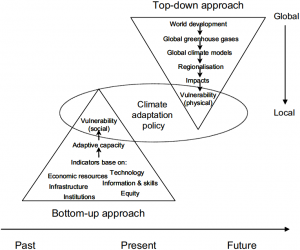

A “top-down” approach to climate change negotiation starts at the highest level and works its way down. In the international regime of the UNFCCC, the Parties come together to decide on a commitment and in theory will be held responsible to uphold this commitment. In contrast, in a “bottoms-up” approach, commitment and action start at the local level and work up to the international level. Daniel Bodansky in The Durban Platform: Issues and Options for a 2015 Agreement argues that both are relatively equal effectiveness because “facilitative bottom-up approaches score well in terms of participation and implementation, but low in terms of stringency; top-down contractual approaches the reverse” (Bodansky, 2). Basically, the strengths of one are the weakness of the other and vice versa. However, not everyone agrees that the two approaches yield equally effective, or not effective, results. Steve Rayer in How to Eat an Elephant: a Bottom-up Approach to Climate Change Policy (Abridged Version here) states that although top-down approaches are useful for setting goals and standards that all Parties should meet, he doesn’t believe in “setting grandiose emissions targets without any plausible technological pathway for achieving them” (Rayer, 620). Rayer believes that UNFCCC and the Kyoto protocol represent the failures of top-down approaches because they rely too heavily on politicians who don’t necessarily prioritize climate change (Rayer, 616).

While I don’t necessarily agree that top-down and bottoms-up approaches result in equal effectiveness, I also don’t believe that the UNFCCC or the Kyoto protocol is a failure. As the age-old idiom goes “there are too many chefs in the kitchen” when it comes to climate change negotiations. However, that doesn’t mean you put each chef in his own kitchen. In a top-down approach there are too many Parties who want too many different things to find an effective solution that makes everyone happy. However, in a bottom-up approach, there is no one to enforce that changes are being made and that everyone is working together. Climate change is a global issue so it needs to be dealt with in some respect in a global arena. At the same time, local governments and groups have a better understanding on what is practical and possible in their culture and community. A multi-track approach that can allow policies to start at the local level, but still holds people responsible at the international level is the best way to continue climate change negotiations in the future.

Bodansky, Daniel. “The Durban Platform: Issues and Options for a 2015 Agreement.” December 2012.

Rayer, Steve. “How To Eat An Elephant: A Bottom-Up Approach To Climate Policy.” Climate Policy (Earthscan) 10.6 (2010): 615-621. Environment Complete. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

Maeve – the article by Steve Rayner is a great find. Thanks for adding this to the discussion. Another paper from Rayner and co-author Gwyn Prins that is worth reading is “The wrong trousers: radically rethinking climate policy.” See https://www.scribd.com/doc/215004382/The-Wrong-Trousers-Radically-Rethinking-Climate-Policy.