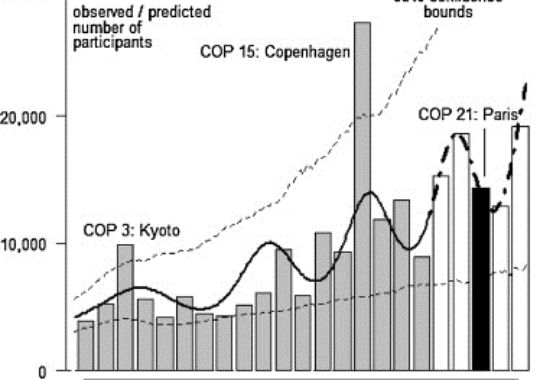

Throughout its history, the UNFCCC negotiations have been struggling to find the right kind of agreement that will have enough stringency in regulating emissions to avoid dangerous warming, participation from many nations involved in the global problem of climate change, and compliance of the pacts agreed upon by the Parties. The Kyoto Protocol was, for some parties, too contractual of an agreement. The US refused to ratify it, Canada dropped out rather than legally exceed its set emission limits, and Japan and Russia decided not to accept the second commitment period targets. This top-down approach, a focus on the international governance of the UNFCCC, made participation and compliance difficult, and, currently, global emission regulations are not powerful enough to keep us from exceeding a 2ºC warming.

In order to step away from this sort of tactic, the bottom-up agreement reached in Cancun had nations volunteer their own mitigation and adaptation strategies. This resulted in participation among more nations but, because nations had an incentive to underestimate their capabilities, the agreement exudes a lack of ambition.

How can we find the perfect balance of governance that invites widespread participation, strict obedience to the rules, and ambitious guidelines that give this planet a better chance of staying below a 2ºC increase? The planet is warming quickly and many domestic governments do not seem willing to pass stringent emission regulations. It is difficult to enact a stringent climate policy when nations feel there is no reciprocity. At the same time, watering down an agreement so that more people participate is not enough action to stop dangerous global warming.

The Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP) was established at the Durban Climate Change Conference in 2011. They are working on a protocol or agreement to present at the COP21 in Paris to implement in 2020. They hope for some agreement with legal force and a large impact in preventing dangerous climate change. The ADP needs an agreement with the stringency of a top-down approach with the compliance and participation of a bottom-up method. To do this, the ADP should try both- a mixed track approach.

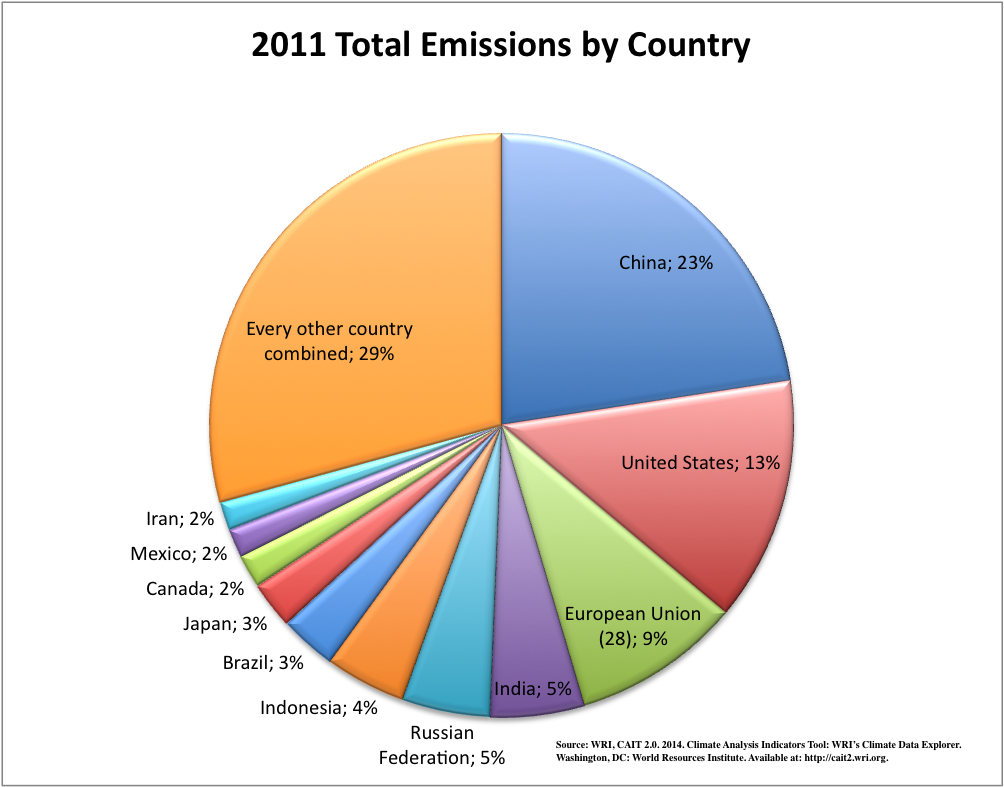

We do not need everyone to participate, but we do need the largest emitters of greenhouse gases to comply with regulations. In the current political climate, a legally binding emission reduction agreement probably would not pass many nations’ governing bodies. The US Senate, for example, does not seem willing to approve a stringent protocol regarding climate change. Because of the recent recession, many nations are hesitant to enact legislation that may decrease GDP or economic revenue in any way. Some agreement is better than no agreement with these countries. A non-legally binding agreement from the bottom-up will allow big greenhouse gas emitters such as the US and China to get involved in reducing their emissions. This may be the best we can do with regards to these countries. However, with a mixed track approach, we would not have to let the political failings of a couple large emitting countries hold the rest of the world back. It is foreseeable that the European Union (EU) and other developed nations would pass a legally binding climate agreement. Like the Kyoto Protocol, they could have an emission trading system and more stringent emission caps. As Bodansky and O’Connor point out, “stringency and participation should be seen as dynamic variables.” Hopefully, the US, China, and India can transition into the legally binding agreement with time and become participants in the emissions trading system.

The mixed track approach is the best solution for our current political situation. It is better to include large emitting countries like the US in a voluntary emission reduction program than send an agreement to their Congress knowing it will not pass. For other nations, a stringent global emission policy is necessary in order to prevent catastrophic warming. Ideally, even nations such as China, Brazil, and India may elect to sign onto the legally binding, top-down track. They may find that it is their nation’s best interest to reduce air pollution, increase energy independence, and be perceived favorably by the EU. With a mixed track approach, policy can retain the best aspects of both the bottom-up and top-down approaches. We can enact more stringent policy with select nations while allowing less compliant nations to participate. Many difficulties lay ahead, but trying this approach my make the negotiating efforts of the ADP more effective.

Works Cited:

Bodansky, Daniel and O’Connor, Sandra Day. “The Durban Platform: Issues and Options for a 2015 Agreement.” December 2012. The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. Web. file:///C:/Users/Jess/Downloads/03%20Bodansky%202012%20durban-platform-issues-and-options.pdf.