In a history class, the covered material often consists of past societies’ wars, plagues, rebellions and leadership transitions. Whereas, it seems that periods of peace and prosperity are glimpsed over in the history books and its importance is disregarded. This neglect for positivity is demonstrated in the climate change’s history where the efforts are often described as failures. Global climate change is a multifaceted crisis and evidently does not have a straightforward solution. However to describe the notion of a “cooperative response” at the COP20 convention as “naïve and contrary to the record of human history” is unfair (Bova, pg 249-50). Bova’s realist perspective is supported from aspects of past climate change governance; yet, the constructivist international relations paradigm is a more appropriate theory due to the climate change policy landmarks, the global participation in the climate change crisis and negotiations’ advancement through science.

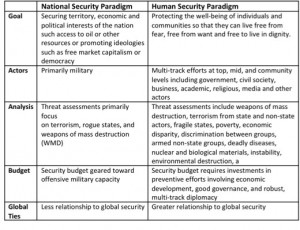

The previous efforts to govern climate change refute the realism view due to: the international efforts and acceptance of climate change, the advancement of international institutions and the number of climate change milestones throughout history. First of all, realism is a power-based regime theory in which states behave to benefit their own-self-interest politically, socially and economically. This theory may be applicable for some countries, but holistically countries have worked cohesively on the climate change crisis. One example of successful international climate change relations is the emergence of various institutions, consisting of countries that share similar climate change interests and goals. The UNFCC and COP are two examples of decision-making bodies that have world-wide involvement to tackle climate change. Other institutions consisting of SBI, POS, EU and G77 are divided based on geography, current conditions, issues and interests; they are all involved in globally collective institutions and are not motivated by their countries own self-interest. The advancement of international institutions has led to the organization and planning of climate change governance, which is the first step in the negotiation process.

In contradiction of the realistic view, the history of climate change has achieved many historic milestones, especially, since the knowledge that human-induced climate change was not accepted in the scientific world until the 1970s. In the last 44 years, climate change has resulted in a change of beliefs, “deepening of cooperation”, “firming–up obligation to act”, “identified problems pressing for a need for action” and the creation of “concrete, legally binding emission reduction commitments” (Bulkeley & Newell 20). The international acceptance of climate change lead to a successful moment in history was when the UNFCC was agreed upon to deal with climate change. Afterwards the Montreal Protocol was passed to stop the use of chemicals that caused the depletion in the ozone. Another success was Kyoto Protocol that binded 38 countries to reduce their emissions (5.2% below levels in 1990) by 2008-12. Despite the United States’ refusal to ratify agreement, overall the EU and G77 did not follow the United States’ self-interested footsteps. Instead they acted in regards to the knowledge that climate change was a pressing issue and become even more determined for Kytoto Protocol to succeed. Regardless of climate change’s complexity and difficulties, there was a strength in climate change’s history for countries around the globe were able to work together through creating institutions and policies.

Although the climate change governance issues had momentum, not every country is participating the global prevention of climate change outlook and behaved with the self-interest as a priority. One of these self-interested nations is the United States for they focused on the developing countries being required to follow protocols rather than focusing on its own high greenhouse gas emissions. One example was when the United States refused to sign the Kyoto Protocol even though they helped develop it, 150 other countries signed it and are highly responsible for greenhouse gas emissions. Another realistic issue is that there are more components that require attention in the next conference. One component is that developing countries such as China, India, Brazil and South Africa have become heavy greenhouse gas emitting countries. These countries now need to be more involved in the negotiation process and have to make vast changes in their organization. From the past, it is evident that all countries including developing nations need to be included/ restricted in the next agreement. Another component is the strong involvement of businesses for in the past countries did not want to make a mistake economically by altering their energy usage. Money necessary for the mitigations and adaptations strategies to be successful, so the involvement of businesses is vital. Although these components have proven to be difficult in the past, there is a clear need for countries to action from the scientific knowledge.

Although the history of climate change is foggy with self-interest intentions, it mainly consists of countries that have acted due to the acquirement of knowledge. First of all, without science/ knowledge, the globe would not be aware of climate change and no efforts to govern climate change would be made. Specifically, the history of climate change begins at the Villa Conference of 1980 when scientist were asked to see if climate change was an issue. From their science, it was realized that further investigation was required and WMO, UEP, ICSU were all created to define climate changes risks. These organizations were key players in the efforts to govern climate change. Most importantly, the most credible source used for climate change is the IPCC which is composed of a variety of scientist whom inform the globe about climate change. The IPCC report determines how countries act towards climate change, which explains that the constructivist international relations theory is the most applicable for understanding the climate change governance.

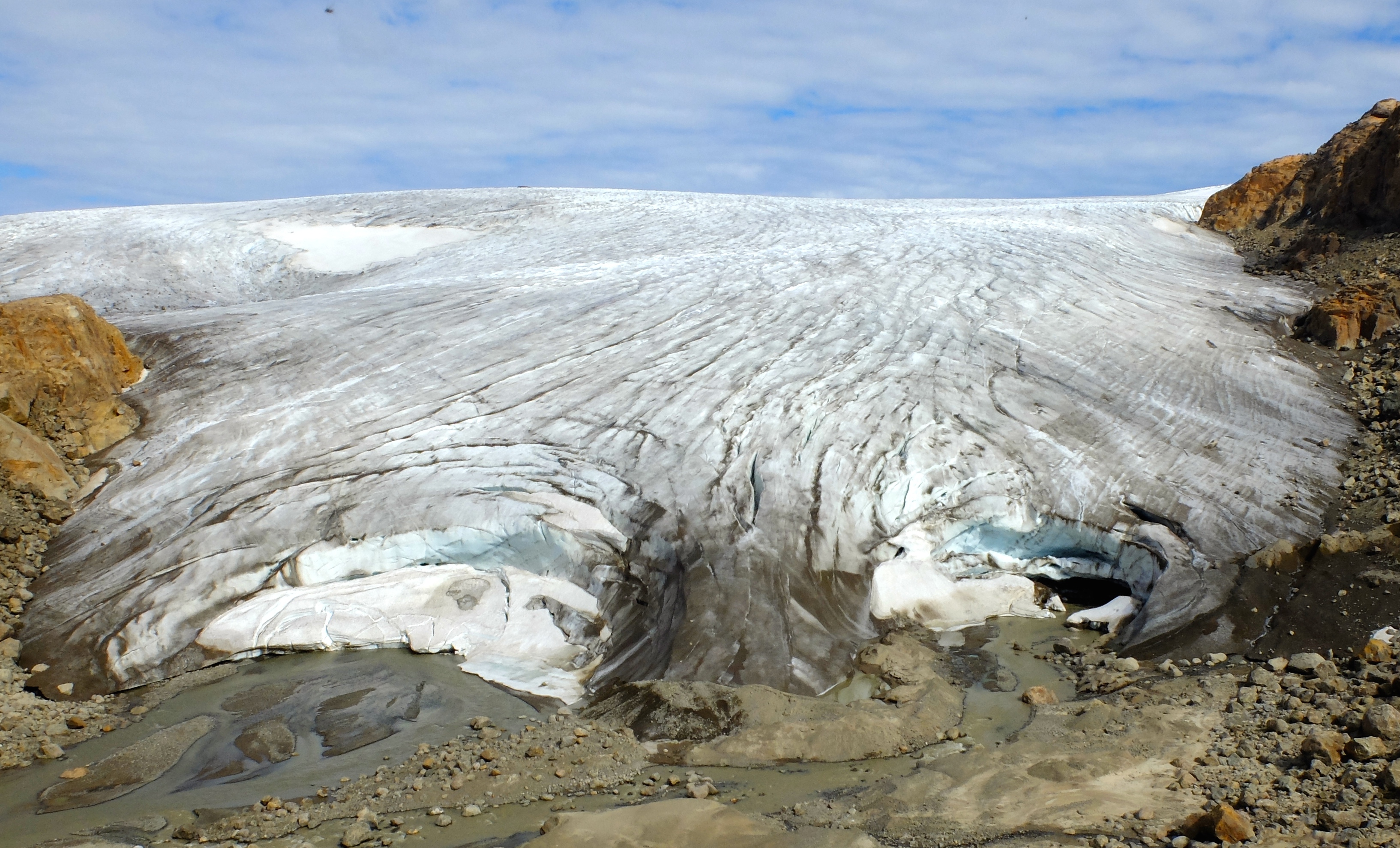

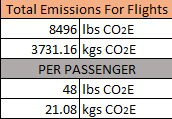

Although, there are aspects of power-based international relations theory seen throughout the history of climate change, it seems that most of the efforts were based upon knowledge from scientists. Science has played a detrimental role in climate change governance for resulted in global participation and acceptance of climate change. Although, climate negotiations will be difficult, if countries rely on the pressing dangers that science has demonstrated in the IPCC reports, countries can work together to avoid such issues and avoid the outcome of the youtube video below.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B11kASPfYxY” title=”Climate%20Change%20Negotiations%20Realism%20Depiction”]