Thus far our time in Lima has been spent sightseeing, for both people and places. We have been spending our days at Voces por el Clima interviewing delegates and representatives from various countries, Peru, Bolivia, Netherlands, and the Democratic Republic of Congo to name a few. While also exploring Lima outside of COP venues, we continue to run into party members and representatives. We were fortunate enough to have dinner with Gabriel Blanco a delegate from Argentina who has attended 9 previous COPs. Through a more relaxed interview involving cebiche and cerveza, Señor Blanco held nothing back about Argentina’s insufficient climate action. While it was surprising to hear about Argentina’s climate denial, it was even more surprising to me that Argentinas government continued to send delegates to a convention in which the argentine people had very little commitment towards. Leaving that dinner was a bit frustrating to hear that despite this being the twentieth conference of the parties, some governments are still in disagreement about the changing climate which is greatly impacting the lack of education for its citizens. Therefore a cycle of negligence occurs. However, Gabriel Blanco seemed somewhat optimistic for the outcomes in Lima, and we told him we will come to Argentina to help change the minds of the many Argentines who remain apathetic towards climate change.

Artistic Expressions of Climate Change

When photographer and climate scientist James Balog visited Dickinson College a few weeks ago, our community was introduced to a new way of looking at climate issues in a means expressed through art. Balog expresses his concerns of climate change in the best way he knows possible, through his photography. His work was so stunning and moving that the movie Chasing Ice was made to motivate society and create a sense of urgency in calling for action.

Furthermore, on Monday October 20th and Tuesday October 21st, the mosaic group spent time in Washington DC listening to many guest speakers with several different backgrounds. Our last speaker, Keya Chatterjee, of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) had a very optimistic and positive aspect on the direction that the climate change movement is headed. She mentioned the power of art and music in modern society and suggested that maybe if climate concerns were expressed though different forms of art that this might have a monumental affect on modern society.

The New York Times article, “Extreme Weather” Explores the Climate Fight As a Family Feud, by Andrew C. Revkin, talks about the play “Extreme Weather”. Play writer Karen Maldpede, uses “theater to explore the clashing passions around human-driven global warming and our fossil fuel fixation” (Revkin). Included in this article is a video of author Andrew Revkin singing his song “Liberated Carbon”, listening to this song for the first time made me chuckle; the idea of climate change expressed though song is such a foreign concept to me.

[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZOXgM3Fbr_4″]

Andean Civilization and the US Food System

This semester I am taking South American Archaeology as one of my four classes. Right now, we are discussing pre-Incan Andean civilizations, some of which inhabited the area of Peru that we will be visiting on our upcoming trip. While developments in pre-Incan cultures might not be directly related to climate change, the topic of climate comes up often in the study of pre-Incan cultures, as it plays an important role in societies that are so connected to the Earth and the environment. There was, of course, no anthropogenic climate change during the pre-Incan period, but climate affects civilizations nonetheless. In fact, the collapse of the Tiwanaku was caused in part by a changing climate.

The Tiwanaku, a civilization present during the Middle Horizon period of Peruvian history, from about AD 500-1000, was already seeing fragmentation in their society near the late 11th century, as evidenced by the defacing of ritualistic monoliths– representing a ritual “killing” of the monolith’s ritual and power. But, beginning in the late 11th century and continuing for a few hundred years, a drought hit the altiplano region of the Andes, the location of the Tiwanaku capital. At the time, the Tiwanaku had a centralized food economy, and the drought put stress on this, exacerbating fragmentations in an already disjointed culture. Local production systems came under the control of local corporate groups exercising local autonomy over their region, taking power away from the elites of the society (Janusek). Tiwanaku civilization was really an alliance of many different ethnic groups, which probably made it easier for it to break apart.

Obviously, a development such as the one seen with the Tiwanaku can inform our current situation with global warming. For instance, the US, similar to the Tiwanaku, has a centralized food economy that could be damaged by the effects of current climate change. Because all areas of the country depend on a centralized production center, the whole country will feel the effects of climate change, as a decrease in crop yield in one part of the country will affect the quantity and quality of food shipped to the whole of the country. We are not only facing at long-term drought, as the Tiwanaku did, but also rising oceans, more extreme weather, and hotter global temperatures. While we might have a better infrastructure than the Tiwanaku did, if we don’t do anything, at some point we will not be able to deal with the fallout from current climate change. Further, even if the US can deal some of these effects, the same cannot be said for less developed countries. These changes will not only have damaging effects on human populations, but might even modify economic and government systems. Already, and as Michael Pollan hints at in his book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, we are seeing, in some areas of the US, movement towards supporting locally sourced food (Pollan). Could this represent regions of the US starting to exhibit more local autonomy, due to the stresses put on the world’s economic and political systems by climate change? Furthermore, private corporations and subnational governments are working together to form transnational governance networks, for the purpose of working to mitigate and adapt to climate change below the realm of international negotiations, as they realized some of the failures of the UNFCCC and Kyoto Protocol. I’m not saying our whole civilization is going to collapse due to climate change, but climate change will definitely affect more than just our daily everyday life. It will affect the whole of human civilization.

Works Cited:

Janusek, J.W. 2004 Household and City in Tiwanaku. In Andean Archaeology, edited by H. Silverman, pp. 183-208. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

Pollan, Michael. The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals. New York: Penguin, 2006. Print.

Have your cake and eat it too with the “Mixed-track” Approach

The Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP) has two objectives taken on by two different workstreams. The goals of the ADP are to develop a new framework that will govern all parties under the UNFCCC by the COP 21 in 2015 and to close the ambition gap by ensuring the highest mitigation efforts by all parties. Keeping in mind the golden number, 2 degrees Celsius, is the limited amount of global temperature rise. The complexities of climate change involve multilevel governance. Finding the best approach towards climate governance is a heavily debated topic, given the difficulty of reaching a global agreement. Two opposing approaches are a top-down approach and a bottom-up approach. These approaches are used to link the economy and greenhouse gas emissions. Top-down involves a, “contractual approach favoring binding targets and timetables” (Bodansky, 1). While bottom-up involves, “facilitative approach favoring voluntary actions defined unilaterally”(Bodansky, 1). David Bodansky argues that an effective international agreement relies on multiple variables: stringency, participation, and compliance. However, “weakness along any of these three dimensions will undermine an agreement’s effectiveness” (Bodansky, 2). Which is why he argues both models should be merged in order to cumulate an effective agreement.

The Kyoto Protocol was expected to lead a long-term top-down approach for mitigating climate change. Developed and developing countries could not come to a consensus in the negotiation process. Instead, countries have taken on their own climate obligations through a bottom-up approach. The failure of the top-down approach through the Kyoto protocol allowed for alternative approaches to take way, such as the Cancun Agreements. At Cancun, “the Brazilian government declared it would halt all deforestation in Brazil by 2025” (King, 2011). A bottom-up approach essentially implements policies at the lowest level of organization. Thus, proposing the idea that action can be taken at every level. There are numerous municipal initiatives and cities that are the centers of innovation for more sustainable practices. While a top-down approach focuses its attention on mitigation, a bottom-up approach concentrates on adaptation and the notion of vulnerability. Local approaches tend to have more short-term results, whereas top-down methods involve long-term impacts.

A hybrid, or “mixed track,” approach will be necessary in order to establish absolute commitments. Both approaches have different strengths and weaknesses, but together the weaknesses are compensated. For example, bottom-up attracts participation and implementation but does not effectively enact regulations. On the other hand, top-down results show the opposite. Mitigation and adaptation are both equally important in combating climate change and can both be reached through a mixed track approach of governance. We must not only rely on global agreement and regulation, but also on local implementations and participation. A legally binding treaty would ensure compliance but in addition we need local projects and governance in order to take fast action. The combination of both top-down and bottom-up approaches will be the most effective route in achieving the post-2020 goals of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform on Enhanced Action.

Works cited

David Bodansky, “The Durban Platform: Issues and Options for a 2015 Agreement,” Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (2012): 1-11.

King, David, and Achim Steiner. “Is a Global Agreement the Only Way to Take Climate Change?” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, n.d. Web. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/nov/27/durban-climate-change-delivery

Leisure or Consumption?

In tonight’s Clarke Forum lecture with Mark Price, Ph.D. entitled, Fighting the Runaway Inequality: The Minimum Wage Controversy, a little light bulb went off.

When discussing the increased productivity of American workers occurring alongside the fall in the minimum wage adjusted for inflation. Thus, people are producing more while simultaneously making less money in wages. This extra time they have, Dr. Price pointed out, low-wage workers could either increase consumption or increase leisure time. As can be assumed in an American culture defined by consumerism, most chose more consumption and thus their activities in their free time require them to make even higher wages. This raises a predicament putting low-wage workers into further and further debt.

Going off of this, I started to think about what would happen if we consumed less? Our industrialized European peers got the message, pairing up industrialization and leisure, but America took the consumption road, leading to even more overworked members of society wanting more and more. To see what I mean, check out the “Story of Stuff” below.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9GorqroigqM”]

So what does this have to do with global climate change? Imagine if Americans started to spend their free hours enjoying low-cost leisure time instead of consuming and working extra hours to fuel their consumption. First of all, if society really changes its ways from consumption, the amount of “low-quality” products requiring endless amounts of greenhouse gas emissions. Secondly, most low-cost leisure activities involve the outdoors in some way, whether in the form of hiking, a free concert in the park, swimming, walking, running, playing pick-up games, having picnics, gardening, biking, and I could go on forever. As we talked with James Balog in the Treehouse the morning of his lecture, his and many others’ environmental ethic comes from their love for spending time outdoors. Thus not only could more leisure time lead to less greenhouse gas emissions, but it could boost people’s environmental ethics as well, making it more likely for them to take action against climate change and urge others to do the same.

The tricky part is figuring out how to change a key component of society in place for 200+ years. Any ideas? I know I will start by spending my free time doing things outside.

The 411 On the UN Climate Summit

UN Climate Summit- Catalyzing Action video

Up to 400,000 people joined my classmates in New York on Sunday and millions more from around the world marched as well for action to address climate change. This global march addressing global climate change kicked-off “Climate Week- NYC” based around the Tuesday September 23rd UN Climate Summit, called by Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon.

Ban Ki Moon called this summit on September 2, 2014, calling on a variety of leaders to come together to take more definitive actions against climate change. The UN Climate Summit is separate from the UNFCCC and thus separate from COP politics. Ban Ki Moon quoted his frustration with climate action lacking ambition thus far pushing his goal for this summit  bring more ambitious climate work to life.

bring more ambitious climate work to life.

Specifically there are two goals of the Climate Summit. One, “to mobilize political will for a meaningful universal agreement at the climate negotiations in Paris in 2015” and two, “to catalyze ambitious action on the ground to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and strengthen resilience to the changes that are already happening”. (Ban Ki Moon 2012).

Although the UNFCCC is separate from the Climate Summit, there are many parallels in the frustration with (lack of) progress thus far and the need for wider-reaching agreements, both in participants and commitments. Ban Ki Moon specifically invited not only governmental world leaders but also business, finance, and societal world leaders. By doing this, he aims to encourage multi-lateral, multi-player actions as many theorists (such as Bulkeley and Newell) claim. Furthermore, the Secretary General called on attendees to bring with them “make bold announcements” (Ban Ki Moon 2012) regarding new commitments to combatting climate change.

Addressing recent requests by developing countries to include other action policies besides emission mitigation, the summit will address the political possibility for a stronger 2015 agreement, emissions reductions, and adaption to climate change.

The bottom line, Ban Ki Moon sees his Climate Summit as a way to kick-off more ambitious, accelerating negotiations and actions against climate change. It will be interesting to see if world leaders arrive tomorrow with this idea in mind, or if it will be as sticky as COPs have gotten in the past.

Throughout the summit, you can follow the conference via the web here.

Climate Change and Indigenous Communities in the Arctic

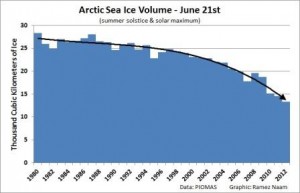

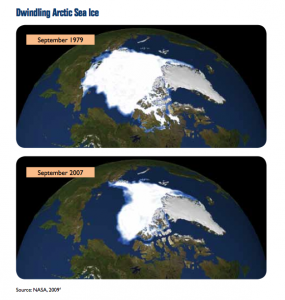

The Arctic, defined as the area north of 66 degrees 33 minutes North latitude, a.k.a. the Arctic Circle, is home to a multitude of indigenous people, among them the Inuit in Greenland, Canada and Alaska, the Inuvialuit in western Canada, the Athabaskan in Alaska and Canada, and the Saami in Norway, Sweden, Finland and northwest Russia. These people’s cultures and traditional lifestyles are shaped by the Arctic environment, and because of this these people are very vulnerable to climate change. For people who depend on a stable local environment to support and sustain their settlements and lifestyle, a changing climate can have a very injurious effect. One of the ways in which the warming climate can adversely affect indigenous people is that the weather becomes less stable and therefore harder to predict. Experienced hunters and elders have reported that traditional techniques of predicting the weather are becoming ineffective, with storms occurring without warning and wind direction changing suddenly. This unpredictability in the weather can present problems when trying to figure out the best times to, say, dry fish, or lead a hunting party. Yet another problem is that the changing climate has brought about more freezing rain. This affects snow characteristics, and nowadays, Arctic natives report that there is a lack of good snow that can be used to build igloos. This is causing an increase in injuries and deaths for members of hunting parties because the hunters are unable to build shelters quickly enough when faced with a sudden storm. Another problem caused by freezing rain is that much of the wildlife of the Arctic, including reindeer and musk ox, cannot find food in the winter due to the thick layer of ice covering these animals’ usual food sources. This will in turn affect the indigenous people who depend on these animals for food. Climate change has also caused sea ice to decline in both extent and thickness. With less sea ice, seas are stormier and more violent, which is dangerous for hunters, as the thin sea ice is very unsafe for travel This also adversely affects anyone else who wants to use the sea ice for transportation, either walking or using sleds. Animals, such as walrus and polar bears, are beginning to see the range of their habitats decreasing, threatening their populations and adding stress to those people who depend on the animals for food and for the warmth that their pelts provide. The indigenous people living above the Arctic Circle depend on a stable environment and stable weather conditions to support their lifestyles, but climate change is causing the landscape of the Arctic to change. Sea ice is less stable, weather conditions are unpredictable, and even the surface of the ground is changing. This is affecting the food supply of these indigenous Arctic people, along with their travel and safety. Although the indigenous peoples of the Arctic might seem as far removed from our society as one can get, we cannot ignore their concerns and troubles, as it is almost a foreshadowing of what might happen to us if we ignore climate change for long enough. Thanks to Neil Leary for the link to the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment: ACIA, Impacts of a Warming Arctic: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Realism Loses Touch with Reality

There are three main paradigms of international relations theory: realism, liberalism, and constructivism. Realism states that all states are driven to act in their own best interests in unchangeable world of anarchy, requiring a large military at times to maintain security (Bova 8-19). Liberalism states that global cooperation and movement past realism is possible through three main ways- international institutions, commerce between states, and the spread of republics less likely to sway towards war (Bova 19-22). Constructivism states that although states tend towards power-seeking opportunities, the anarchy of international relations does not necessitate such behaviors and furthermore, new norms and non-state actors such as transnational organizations and individuals also play a part in whether states follow a realist path of action or not (Bova 24-26). These paradigms are used to understand behaviors and interactions between actors in the international arena. Thus members of each paradigm have a different take on how global politics will play out in regards to global climate change. Dr. Russell Bova, in his textbook “How the World Works,” writes “in short, for realists, the expectation that global environmental crisis will lead to cooperative responses is both naïve and contrary to the record of human history” (249-50).

Efforts thus far in governing global climate change include, among other things, forming the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol, and hopefully soon, a new mitigation agreement to replace the Kyoto Protocol in COP21 in Paris in 2015. However, these are not the only methods by which states and other parties in the world address climate change. Other efforts include private encouragement of sustainable, renewable energy development (Held, Roger, Nag 19), sub-national government efforts like carbon trading within individual U.S. states, and NAMAs, or National Appropriate Mitigation Action. Evidence from efforts to govern global climate change do not support this realist view, and in fact, none of the above paradigms perfectly explain the global climate change international responses and governance. Nevertheless, liberalism best describes the recent history in global climate change governance while constructivism describes the near future of global climate change governance.

Nation-states and interstate governance is only one facet of addressing global climate change. Any paradigm focusing on states as the main/only actor in international relations ignores some of the most important actors global climate change governance. Thus, realism which argues nation-states are the only actors in the international relations arena fail to acknowledge key actors in global climate change governance and thus do not explain current trends in global governance. Liberalism proves more hopeful in terms of its acknowledgement of non-state actors, as exemplified by institutional liberalism. Institutional liberalism looks to the formation of formal international governance bodies and laws to turn the world away from a realist fate. Such institutions include the UNFCCC and Kyoto Protocol. However, as Bulkeley and Newell point out in their introduction, the multi-scale, multi-actor nature of global climate change problems requires a “shift away from the position that the nation-state is the only or necessarily most important unit of climate politics” (4). Thus the institutions that liberalists propose still do not align with newer attempts to govern global climate change including non-state actors. Looking backwards, liberal institutionalism explains the Kyoto protocol and UNFCCC but fails to explain what the future might hold if politics are to go down the path Bulkeley and Newell suggest.

Lastly, constructivism may be the most promising paradigm to explain current attempts at global climate change governance as it touches on the need for inclusion of non-state and transnational actors as they promote ideas which promote moving away from realist state behavior. The key to constructivism is that it does not require a structural change such as international law to govern a state’s behavior away from realist tendencies (Bova 27). Therefore, it offers a third option to addressing climate change on a global level besides institutionalism (liberalism) and war (realism). Because constructivism does not require a state-centered governance structure, it falls along the line of Bulkeley and Newell’s thinking that future politics will move past state-centered governance structure as more and more types of actors hold important parts in mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Realism developed to explain countries’ actions in post WWII and Cold War politics (Bova 8) and has lost its relevance as issues like climate change require a cooperative multi-level, multi actors approach to solve the problem. Consequently, the newest paradigm of constructivism, best explains why global governance regarding climate change is going towards a less state-centric approach. Wide-scoped problems call for wide-scoped responses as is reflected in a turn to the constructivist approach to global governance problems.

Works Cited

Bova, Russell. How the World Works. Longman Publishing, 2011. Print.

Bulkeley, Harriet, and Peter Newell. Governing Climate Change. New York: Routledge, 2010. Print.

Held, David, Charles Roger, and Eva-Maria Nag, eds. “Editors’ Introduction: Climate Governance in the Developing World.” Climate Governance in the Developing World. Malden: Polity Press, 2013. 1-25. Print.