The Food Waste Problem

The Food and Agriculture Organization defines food waste as “the decrease in the quality or quantity of food resulting from decisions and actions by retailers, food service providers, and consumers.” In the United States – as well as globally – we waste approximately 30-40% of our food (Canon, 2023). This tendency has significant implications for the climate, from growing landfills to increased greenhouse gas emissions. But how did we get here in the first place? Where do these steep numbers come from?

Sources of Food Waste

There are four main pathways of food waste: production, post-harvest/post-handling, processing, and distribution/consumption. Food can be wasted at any point in the food supply chain. At the production level, food may be lost due to overproduction and surplus. At the post-harvest/post-handling level, food may be thrown away if it does not meet industry cosmetic standards. At the processing level, consumer preferences (e.g., pre-peeled, pre-chopped) lead to the waste of viable produce parts. Last but not least, distribution houses a particularly pervasive problem: food labels. Contrary to popular belief, these labels actually have nothing to do with food safety (Tanigawa, 2017). If we can’t trust labels, then, how do we know when to throw things out?

Food Waste Solutions

While each pathway of food waste contributes to the wider problem, we can look to each pathway for solutions as well. On the consumer level, we can spread awareness to adjust behavior. With the case of food labels, we can teach individuals how to assess food safety and expiration using qualities like smell, texture, color, and taste. On the processing level, we can modify expectations to increase acceptance of cosmetically “imperfect” products. In terms of production and distribution, Pennsylvania has some excellent local initiatives. The Pennsylvania Agriculture Surplus System reimburses farmers for donating their surplus goods. Pennsylvania is also home to many Amish “Bent n’ Dent” grocery stores, which sell damaged products at discounted prices. Dickinson College students interested in a local Bent n’ Dent can check out BB’s Grocery Outlet, just 18 miles away in Newburg!

BB’s Grocery Outlet – “Bents, Bumps, and a Bunch of Bargains”, Kirb Witmer

Innovative Solution: Biodigesters

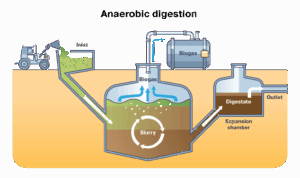

Biodigesters are a unique and growing solution to food waste. These systems use anaerobic digestion to break down organic material and convert it into two reusable resources: biogas and digestate. These byproducts have numerous utilities. Biogas can be used for cooking, heating, electricity, and even vehicle fuel. Digestate can be used as a nutrient rich fertilizer – a much more sustainable alternative to synthetics. The benefits of biodigester implementation are vast, and they go beyond the environment. Women and children in developing countries, for example, can be significantly advantaged in terms of health and life satisfaction with the help of biogas (Steiman, 2020).

Diagram of anaerobic digestion in a biodigester, Power Knot

The Dickinson College Farm has a biodigester of its own, taking waste from college dining locations, local restaurants, and livestock to generate electricity. This project is a prime example of preventing waste by turning it into something valuable!

Generating Change

While food waste initiatives are highly necessary, it can be hard to foster engagement and participation. This is where we have to get creative. A 2019 study of an Austrian food sharing program explored member’s motivations for participating and found that they were influenced by the following: emotions and morality, identity and sense of community, reward, social influence, and instrumentality (e.g., desire to save food from being wasted) (Schanes & Stagl, 2019). Using what we know about consumer desires and drives, we can make intentional program design choices to shape the most effective programs. In this way, food studies can harness consumer and market psychology to understand and shape our food-related choices.

References

Canon, G. (2023, May 14). Has this food actually expired? Why label dates don’t mean what you think. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/13/food-labels-expiration-dates-safe-to-eat

Dickinson College (Director). (2022). From beer to biogas: Creating green energy using brewer’s grain & farm waste [Video recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jz1aBf7CTR0

Gunders, D., & Bloom, J. (2017). Wasted: How America is losing up to 40 percent of its food from farm to fork to landfill. Natural Resources Defense Council. https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/wasted-2017-report.pdf

Schanes, K., & Stagl, S. (2019). Food waste fighters: What motivates people to engage in food sharing? Journal of Cleaner Production, 211, 1491–1501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.162

Steiman, M. (2020). Women and home-scale biogas: Benefits, barriers and insights from US-based innovators.

Tanigawa, S. (2017). Biogas: Converting waste to energy (J. Stolark, Ed.). Environmental and Energy Study Institute. https://www.eesi.org/papers/view/fact-sheet-biogasconverting-waste-to-energy

It is interesting to consider the food waste associated with overproduction in the context of climate change. Farms overplant to accommodate risks (Halpin, 10/13/25). Changing this habit is complicated, because it enhances the resilience and reliability of our food systems amidst environmental disruptions, which are likely to intensify in frequency and scale with climate change.

As mentioned, at the processing stage of the food supply chain, consumer preferences generate waste. While these are not necessarily susceptible to change, we can reduce waste by improving the efficiency of cutting methods (Wasted, 2017). It is also important to note that while pre-cut produce has a greater environmental impact, it can utilize produce that is not fit for retail (Wasted, 2017).

The post also mentions that the introduction of biogas systems benefits the lives and health of women in developing countries. However, reduced demand for wood gathering eliminates a central social opportunity, and other activities must substitute (Steiman, 2020).

Something that resonates with me from this blog post is the emphasis on utilizing consumer emotions and collective engagement to advance food waste initiatives. This reminds me of how environmental science initiatives must similarly frame problems in terms of the values of an individual in order to gain support.

The blog post highlights how deeply food waste is embedded across the supply chain, and it pushed me to think about waste not just as a consumer issue but as a systemic one. The discussion of misleading food labels especially resonated with me, since I grew up assuming expiration dates were strict indicators of safety. Learning that these labels rarely reflect actual spoilage has made me much more comfortable assessing food with my senses instead of defaulting to the trash. I also appreciated the emphasis on creative, community-based solutions. The Pennsylvania Agriculture Surplus System and local Bent n’ Dent stores show how policy and markets can redirect edible food rather than letting it become waste. This reminded me of class discussions about how ethical food practices often depend on accessibility not just personal effort. Similarly biodigestors demonstrates how waste can become a resource, aligning environmental sustainability with practical energy needs.

The motivations identified in the Austrian food sharing program felt extremely relevant. Programs that tap into these drivers may be more successful than those relying solely on guilt or information. Personally, I’m most motivated by avoiding waste out of a sense of responsibility, but convenience barriers still get in the way. Posts like this help illustrate waste reduction as both achievable and socially meaningful.

You bring up great points about food waste! I agree that more people need to be educated about food waste, especially as it relates to expiration dates. This is something that I was unaware of until reading about it for class. These dates refer to the food’s “best by” date, when it will have its best flavor or quality, not to actual unhealthy levels of spoilage (Canon, 2023). These companies just want the best version of their product to be consumed to keep a good reputation. It is important people know this so as to stop wasting perfectly good food.

I also like how you brought up the different pathways of food waste because when I think of food waste, I only think of the waste from the consumer, but so much gets wasted even before distribution and consumption in the production of foods. The example that exists here on campus of the biodigester is a great solution to food waste. Many institutions can lessen their impact on the environment by converting their food waste into biogas. The spread of solutions like this are important at a time when we face issues from the climate crisis.