On our last day in France, we visited Le Potager du Roi, the little-known technical gardens within the larger decorative gar

The entrance to the tunnels, overseen by the statue of Jean-Baptiste de la Quintinie. Image courtesy of Isabella Heckert (2025).

dens at the Palace of Versailles. Created for Louis XIV’s own kitchens by the lawyer Jean-Baptiste de la Quintinie, they have been used to perfect tree and vegetable gardening techniques for centuries. The gardens, which once hosted elaborate growing infrastructure such as hot water heated greenhouses with coffee plants and thousands of fig trees in wooden boxes, are organized in circles around a central fountain. A system of tunnels runs below the gardens. Today, they are used for storage, but in Louis XIV’s time they were hiding places for the gardeners when the king wished to view his gardens from his terraces.

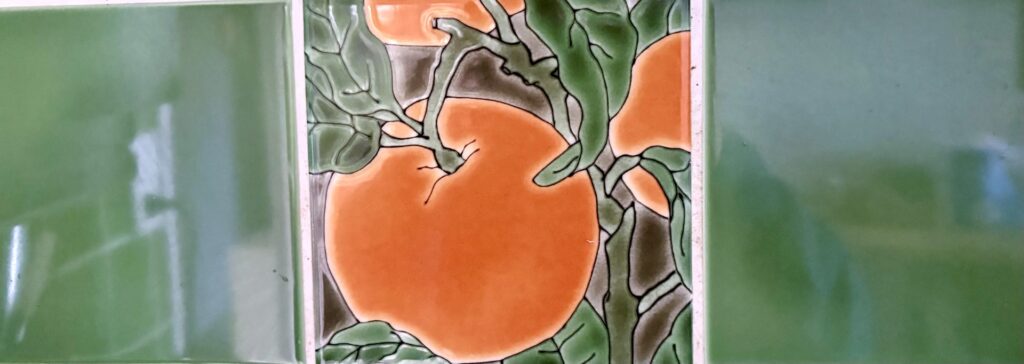

Many of the innovative techniques used by Le Potager du Roi today predate even the gardens themselves. The “espalier” technique, which was developed by the Romans, involves planting trees against walls to retain heat and extend the growing season. This is usually done with fruit trees, which can live for over 150 years in espalier formation (Wisconsin Horticulture). Espalier planting can also be practiced with fencing instead of walls for a similar result, as seen surrounding the garden plots. The result is that all sorts of crops, including beans, potatoes, tomatoes, and many types of fruit, can be grown year round.

The view of the gardens from the terrace. Image courtesy of Isabella Heckert (2025).

However, much of the original infrastructure of the gardens, including the figs, were destroyed in the “rationalization” efforts of the 20th century. The horticultural school switched focus to agricultural engineering and many of the historical elements were lost. Today, the gardens are working to restore the “patrimony” of Le Potager du Roi using the palace’s extensive archives. For example, the gardeners are currently trying to restore the hundreds of species of apples and pears that were once grown in the potager using maps and records of what was planted during the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV. The horticultural school has also switched focus again, and is now training gardeners to work in historical and city-based spaces with “sensibility” for the cultural heritage of each site.

An example of the espalier technique on the fence surrounding a garden plot. Image courtesy of Isabella Heckert (2025).

It is ironic how Le Potager du Roi, which were created to provide food only for the king of France, now practices the same sustainable agriculture techniques as the urban, training, and community farms we visited throughout France. They practice cover cropping, agroforestry, crop rotation, and, as a publicly owned site, have always been organic. Their produce is now sold in the local boutique or to the many producers in France who transform crops to finished products. Inequality was built into the very structure of the garden, with its terraces and tunnels, and now they are open to the public. I felt this was an extremely fitting end to our exploration of the many ways French food systems are becoming more environmentally and socially sustainable, and find myself feeling hopeful for the changes yet to come.

Sources

Marh, S. (N.D.) Espalier. Wisconsin Horticulture, Division of Extension. University of Wisconsin-Madison. https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/espalier/,