By Tom Forte

NOTE: Bolded text in paragraphs refers to Google map place marks

Introduction James McPherson, historian and author of several books including The Battle Cry of Freedom, claims that,”Gettysburg proved a significant turning point in the war, and therefore in the preservation of the United States and abolition of slavery.” His statement is well founded, as General Meade’s Union Army of the Potomac was able to inflict disastrous losses on General Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia that could simply not be replaced due to Southern manpower shortages. Yet on many occasions over the three day battle, Confederate troops came close to victory. However, aside from acts of valor by Union troops, there were several factors that contributed to Confederate defeat: poor reconnaissance and communication, strong Union defensive positions, poor and insufficient equipment, and strategic errors on the part of General Lee.

The First Day of Battle

General Reynolds (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

The battle began at 7:30am on July 1st, 1863, when two Confederate divisions encountered a division of dismounted Union cavalry under General John Buford to the Northeast of the town of Gettysburg.[1] The Union cavalry, though heavily outnumbered, held out until 10:00am when the Union 1st Corps, under General Reynolds, arrived on the scene to reinforce the hard-pressed cavalry. Although he was able to stave off the Confederate assault, General Reynolds was killed while ordering the men of the 2nd Wisconsin Regiment forward into battle [July 1: 10:40am: Death of General Reynolds]; “Forward men, forward for God’s sake, and drive those fellows out of the woods!”, he was then hit in the head by a sharpshooter and killed instantly.[2]

At 2:00pm, the Confederate assault resumed, except this time reinforced by several more divisions. The Union had brought up reinforcements as well, but they were still outgunned.[3] Due to a salient (or bulge) created on the Union right flank by men under General Barlow [July 1: 2PM: Barlow’s Knoll], the right flank was soon broken and Confederate troops began rolling up the Union line.[4] To add to the this disaster, Union lines along McPherson’s Ridge also broke around the same time, causing the Union Army to go into full retreat.[5] In various states of disorder, Union troops were able to make it to Cemetery Hill to the southeast of Gettysburg. General Hancock, who had been sent forward by the commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, General Meade, to take command of the Union troops engaged at Gettysburg remarked that Cemetery Hill was: “…the strongest position by nature on which to fight a battle that I ever saw”.[6] The next several days would prove him right.

The Second Day of Battle

Confederate Sharpshooter at Devil’s Den (Courtesy of HistoryNet)

During the night of July 1st, General Meade positioned his troops in a fishhook shape in order to take advantage of the extremely defensible high ground to the southeast of Gettysburg.[July 2: Blue Lines] Early in the morning, General Dan Sickles, commander of the Union 3rd Corps, spotted high ground to the front of his troop’s positions, and decided to order his men forward to occupy it. Sickles’ decision is one of the most controversial of the entire war, as his corps was now massively overextended and, like Barlow’s men the day before, formed an easily attackable salient in the Union lines.[July 2, Union Troops Under Sickles] In Sickles’ defense, his choice to advance caught Confederate General Longstreet completely off guard. Due to the absence of J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry, which served as the Confederate’s primary reconnaissance force, General Lee had very little idea of where the Union lines were; in fact, he didn’t know that Union troops had been positioned as far south as the territory the 3rd Corps occupied. This development forced Longstreet to delay his attack until 4:00pm so he could maneuver his troops to properly assault the Union left flank.[7][July 2: Confederate Troops Under Hood and McLaws] Although he was overextended and creating a salient, Sickles’ positions were quite formidable, as the terrain was both rocky and elevated, especially around Little Round Top and Devil’s Den, which gave the defenders a good vantage point and ample cover, while simultaneously hampering the attackers.

When Longstreet ordered his corps to attack at 4:00pm, things initially went well for the Confederates, although casualties were very heavy on both sides. After heavy fighting, Union troops were driven out of the Wheat Field, the Peach Orchard, and Devil’s Den. At the time of the start of the assault, there were no Union troops on Little Round Top, and a brigade under Colonel Strong Vincent was scrambled to defend the hill against the advancing Confederates.[8]

Fighting at Little Round Top (Courtesy of Gallon)

On the extreme left flank, the depleted regiment of the 20th Maine was able to hold out against several Confederate regiments, winning the day with a famous bayonet charge: “Our gallant line withered and shrunk before the fire it could not repel. IT was too evident that we could maintain the defensive no longer. As a last desperate resort, I ordered a charge”.[9]

Charge of the 1st Minnesota (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

North of Little Round Top, the Confederate advance was barely halted at Cemetery Ridge after a desperate charge by the 1st Minnesota; it lost 82% of its men in the process.[10] During the evening, attacks were also made against Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, but the Confederates only gained limited ground at Culp’s Hill and none at Cemetery Hill.[11] Many historians believe that Confederate troops under General Ewell (those that attacked Cemetery and Culp’s Hill) would have been better off used elsewhere on the battlefield and, if shifted south, could have been the additional force necessary to break Union lines on Cemetery Ridge; but again, due to the absence of J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry, Lee did not feel safe making a decision such as this one, and he paid dearly for it.[12] However, Lee’s choice to commit his units to battle in a piecemeal (one at a time) fashion can certainly be criticized. Had Lee had his corps attack simultaneously all along the Union front line, Union reinforcements may have been sent to the wrong locations and potentially allowed breakthroughs.

The Third Day of Battle

Pickett’s Charge (Courtesy of Roadboy’s Travels)

On July 3rd, Lee’s originally planned to renew his attack on the flanks, but that morning Ewell’s small hold on Culp’s Hill was lost and he decided to change his strategy.[13] He would instead assault the Union center, which he believed would be less heavily defended than the flanks by this point in the battle. General Pickett’s division had arrived during the night and it, along with the division of Generals Pettigrew and Trimble, would make the assault with a force of 12,500 men. The attack began at 1:00pm with a massive artillery bombardment that lasted around an hour, then, at 2:00pm, the Confederates advanced.[14] [July 3: 1:00PM: Pickett’s Charge] Unfortunately, due to the large amount of gun smoke and poorly made artillery shells, the bombardment was largely ineffective, and Union artillery quickly began tearing gaps in Confederate lines. Once in range, the Union infantry opened fire. One Confederate brigade was able to make it into Union lines, but it was soon repulsed and the Confederates were forced to retreat under a hail of lead. For the Union Pickett’s Charge was won and, with it, the Battle of Gettysburg.

Conclusion

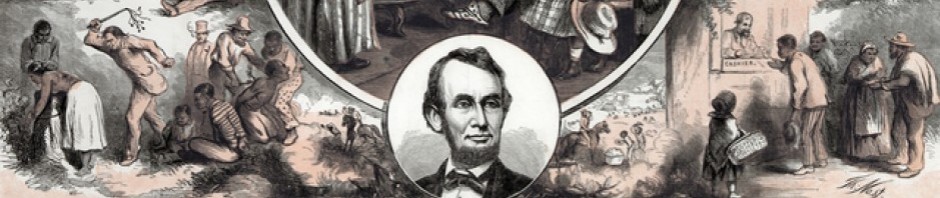

Courtesy of History Channel

Gettysburg, along with the fall of Vicksburg, is considered the turning point of the American Civil War. The Confederate army was never able to fully recover from its defeat, forcing it to remain on the defensive for the rest of the war. Even if Lee had won, it is likely he would have been forced to withdraw anyway, as his army was at ~62% strength following the battle and had no way to easily replenish his loses.[15] Lee’s army could have been completely destroyed, by General Meade was too slow in his pursuit and the Confederate Army was able to escape. The battle of Gettysburg is the 4th deadliest engagement in American military history, with roughly 51,000 total casualties (23,055 Union and ~28,000 Confederate with 7,863 total deaths) after 3 days of fighting in an area just over 9 square miles.[16] To this day, Gettysburg remains arguably the most famous battle of the American Civil War, and hopefully we will not soon forget it, nor the sacrifices that were made on those Pennsylvania fields.

For a more detailed version of this post, click here

[1] Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg–the First Day (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001) 51-68.

[2] Pfanz, 69-79.

[3] Pfanz, 115-130.

[4] Stephen W. Sears, Gettysburg (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003) 224.

[5] Pfanz, 269-293.

[6] David G. Martin, Gettysburg, July 1 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo, 2003) 284.

[7] Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg-the Second Day (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001) 176.

[8] Pfanz, 208.

[9] Joshua L. Chamberlain, “Gettysburg After Action Report, 6 July 1863”, Combat Studies Institute, 8. http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps68440/chamberlain.pdf

[10] Pfanz, 410-414.

[11] Gettysburg Battle-field Commission, comp. Pennsylvania at Gettysburg: Ceremonies at the Dedication of the Monuments Erected by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to Mark the Positions of the Pennsylvania Commands Engaged in the Battle. Vol. 1. Harrisburg, PA: E. K. Meyers, 1893. Accessed November 28, 2016, 204, 424. [Google Books]

[12] Pfanz, 104-113.

[13] Gettysburg Battle-field Commission, 603.

[14] James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1992) 392. [Google Books]

[15] U.S. War Department, ed. “The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.” (Cornell Library).

[16] “10 Deadliest Battles in American History” History Lists, WordPress, 2016. https://historylist.wordpress.com/2008/03/18/10-deadliest-battles-in-american-history/