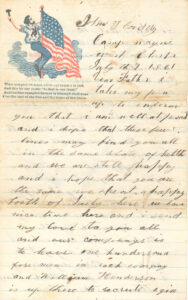

John T. Cuddy Letter: July 7, 1861

John T. Cuddy Letter, January 16. 1863

John T. Cuddy Letter to John H. Cuddy from July 7, 1863 (housedivided.dickinson.edu)

From “having more fun than ever”[1] as a Union soldier in 1861 to wishing “that this ware was over”[2] in 1863, John Taylor Cuddy was a Union Army soldier who documented his experiences throughout most of the Civil War. He was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. During the war period, he experienced events such as Antietam and the Second Battle of Bull Run.[3] As he experienced the trials and tribulations as a Union soldier, he began writing back to his family in letters that are preserved in the Dickinson College Archives. Two of his letters to his father illustrated the different feelings among soldiers over the purpose of the war and its politics as it evolved from 1861 to 1863.

Cuddy’s letter to his father on July 7, 1861, marked one of his earliest correspondences to his family after recently being deployed into the Union Army. He described in his letter his optimism of a speedy end to the conflict. “I hope to get our discharge in three months” [4] is what Cuddy described to his parents in his optimistic letter from 1861. He even elaborated on how life in the Army was fun and exciting while he was stationed at Camp Wayne in West Chester, Pennsylvania.[5] In addition to his social life being described as exquisite in his letters, he also mentioned how all 1600 of the men in his camp had abundant food and clothing. This letter demonstrates a stark contrast to his letters from later in the war.

The language in Cuddy’s 1861 letter to his father connects to the historical context of the early war period. Like many other Americans, Cuddy at the time believed that the war would lead to a hasty conclusion and decisive victory for the United States. As we know during the battle of Manassas, citizens followed the Union Army to Centerville, Virginia to watch what they believed to be the quick end to the conflict.[6] The United States had a clear set of advantages over the Confederacy at the time of the outbreak of the war. Textile mills, iron works, transit networks, railroads, and food production were all resources that the United States had abundantly more of than the Confederate states.[7] Cuddy shared his optimism with his family when he shared his prediction of events that he believed would occur. He truly felt like much of the public. He thought that the Civil War would have been a simple, clear, and decisive victory for the Union. Unfortunately for Cuddy, his perception of a quick end to the war proved to be vastly incorrect.

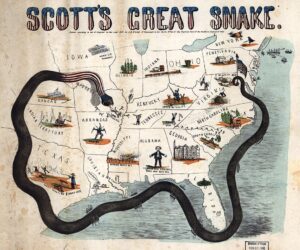

Political cartoon depicting the United States’ blockade on the Confederate states. (wikipedia.org)

Although many Americans were optimistic like Cuddy for a hasty end to the war, many politicians were more cautious on how long they believed the war would last. Abraham Lincoln knew that the Confederacy could eventually fall, but he was not as optimistic as most of the American public in such a hasty conclusions. When thinking of a lack of resources that the Confederates had, Lincoln prepared to demonstrate a form of political power to increase the strain on their economic structures. He believed that through limiting the Confederacy’s availability of resources, most southerners would eventually rebel against the pro-slavery leaders of the Confederacy. [8] Many Americans (including Lincoln) also believed that the South was simply under the involuntary control of “the slave power conspiracy.”[9] He ultimately initiated a Confederate-wide blockade in 1861. Likewise of Lincoln, Cuddy likley believed in this theory as he clearly thought that the United States would easily “make the South in the Union again.”[10] Unfortunately for Lincoln’s popularity and the optimism of the American public, the war was set to rage on for many more years.

Letter from John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy: January 16th, 1863. (archives.dickinson.edu)

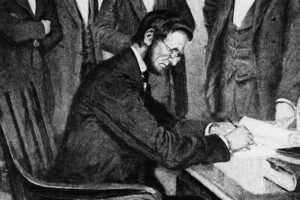

Many began to recognize that the war was going to be much worse than they initially thought. John T. Cuddy’s tone in his letter to his father on January 16th, 1863, demonstrates the shift that occurred in his outlook and opinion of the Civil War between 1861 and 1863. He mentions more than once his desire for an end to the war and that he would never again be a soldier after his service under the Union. He mentioned throughout his letter how he hoped that God would protect him through the war’s end and once again reassured his hopes of an end to the war by the Spring of 1863. He specifically pointed out Abraham Lincoln in his letter as well. He spoke out blaming Lincoln for making the war an issue over slavery and causing it to drag out for so long. Most soldiers for the Union at the time were still contending with the debate over whether Slavery could still exist in a government like the Union after it was reunified.[11] This question that existed was precisely what was going through Cuddy’s head when he learned about Lincoln’s emancipation.

Soldiers like John T. Cuddy were upset with Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation because at the time, factions existed in the Union that dominated Lincoln’s approval. Since Cuddy joined the Union cause early in the war in 1861, he held a viewpoint of most soldiers who believed that they were fighting in the war to preserve the Union more than to abolish slavery.[12] The historical occurrence of the time explains why Cuddy explicitly pointed out that he was upset about Lincoln’s freeing of the slaves. There were conservatives (like Cuddy) who were fighting in the Civil War to preserve the United States and then there were abolitionist who believed that the war was meant to be over slavery. Unfortunately for Abraham Lincoln, he was disliked by both political factions throughout the war. His popularity among anti-slavery Republicans began to slide as he made pro-slavery decisions like when he declared General Freemont’s martial law to begin freeing contraband slaves in the border state of Missouri as null in 1861.[13] Later on, when Lincoln emancipated the slaves in the Confederacy in 1863, he clearly angered conservatives like Cuddy who were very hopeful for an end to a war that they joined to preserve the Union.[14] Imagining how Cuddy must have been feeling at the time, his frustrations over Abraham Lincoln in his letters were clearly justified at the time as he was probably exhausted from the struggles that he and his fellow soldiers were experiencing in 1862 and 1863.

Abraham Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. January 1, 1863 (clarionledger.com)

When we look at John Cuddy’s letters to his father during his time fighting for the United States during the Civil War, his intentions in his first letter were to reassure his family members that he not only was happy and safe, but that the war would be short and easy for the Union. Contrary to his expectations, Cuddy ended up fighting in a brutal three-year war before dying in a prisoner of war camp in 1864.[15] The documentation of his experiences has helped display the political and emotional struggles that the everyday soldiers in the United States Army experienced during the American Civil War.

[1] John T. Cuddy “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, July 7, 1861.” John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, July 7, 1861 | House Divided. Housedivided.dickinson.edu, June 9, 2010. https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/32759.

[2] John T. Cuddy “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, January 16, 1863.” John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, January 16, 1863 | House Divided. housedivided.dickinson.edu, June 9, 2010. https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/32755.

[3] “Cuddy, John Taylor,” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/5511.

[4] John T. Cuddy, “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, July 7, 1861.” John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, July 7, 1861 | House Divided. Housedivided.dickinson.edu, June 9, 2010. https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/32759.

[5] Ibid

[6] Jim Burgess, “Spectators Witness History at Manassas,” American Battlefield Trust (Hallowed Ground Magazine, March 26, 2021), https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/spectators-witness-history-manassas.

[7] Louis P. Masur, “1861,” in The Civil War: A Concise History (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 21-30, 25.

[9] Varon, Elizabeth R. Armies of Deliverance : a New History of the Civil War College edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021, 4.

[10] John T. Cuddy “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, July 7, 1861.” John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, July 7, 1861 | House Divided. Housedivided.dickinson.edu, June 9, 2010. https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/32759.

[11] Gary W. Gallagher. The Union War. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2011, 77. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=597465&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

[12] Joseph L. Locke and Ben Wright, “The American Yawp: A Massively Collaborative Open U.S. History Textbook,” in The American Yawp: A Massively Collaborative Open U.S. History Textbook (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019).

[13] Lorraine A. Williams, “Northern Intellectual Reaction to the Policy of Emancipation.” The Journal of Negro History 46, no. 3 (1961): 174–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/2716047.

[14] Hans L. Trefousse, “Introduction.” In First among Equals: Abraham Lincoln’s Reputation During His Administration, ix–xvi. Fordham University Press, 2005. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13wzxz7.3.

[15] Archives at Dickinson College, “John T. Cuddy,” John T. Cuddy papers | Dickinson College (Archives & Special Collections at Dickinson College, 2021), https://archives.dickinson.edu/collection-descriptions/john-t-cuddy-papers.