All quotations from John Cuddy’s 1863 Letter are written exactly as they appear in his writings

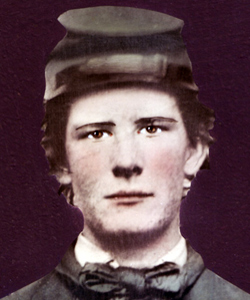

John Taylor Cuddy, like any teenage boy, was eager to prove himself as a worthy, capable young man at the outset of the Civil War. In April, 1861, Cuddy readily joined the Carlisle Fencibles, a volunteer corps of troops formed in his hometown of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Perhaps blinded by both naïveté and a tidal wave of patriotism, Cuddy shared the same hyper-optimistic view of the impending war as many of his fellow soldiers and Northern citizens. In a July 1861 letter to his father, Cuddy bluntly stated, “the north is going to rase a big armey and then we will make the south in the union agin the south cannot stand before our army we will soon lick the south and then we will come home.”[1] In hindsight, it is easy to look upon Cuddy and his contemporaries as wide-eyed and foolish, but every man had his own reason for joining the fight. Contrary to what one might assume, most Union soldiers did not answer the call to arms due to personal anti-slavery sentiments. In fact, in a war whose cause can best be traced back to slavery, many soldiers on the anti-slavery side essentially fought in spite of their personal beliefs on the institution. In January 1863, John Cuddy wrote a very different letter to those he loved back in Carlisle, one that showed just how much he had changed his tune on the war and his reasons for fighting. At the start of the war, John Cuddy exemplified the stereotype of the eager Union volunteer, but as the war droned on, he proved to be the exception to the rule of the dutiful soldier.

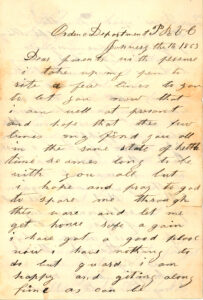

On the 16th of January, 1863, John Cuddy wrote a letter to family and friends with a demeanor much different from that of his jovial first letter home nearly two years prior. In striking contrast with his early-war sentiment, Cuddy then stated, “i hope and pray to god to spare me through this ware and let me get home safe again.”[2] From there, he went on to address his friends, and complained that “Old abe done a bad thing wen he freed all the slaves” and lamented about “fighting for ngroes.”[3] He then made a point of saying how he was sick of the war and the fighting, and how he wished he could come home and be with those he loved. In his final paragraph, Cuddy questioned what was gained by fighting in the war because he felt that more was lost than was gained. He rounded out his writing by once again stating how he wished the war would end, and how he hoped to be with friends and family sooner rather than later.

While it may be tempting to attribute Cuddy’s change in opinion on the war to the shock and distaste of the horrors of battle, the true reason behind this transition was not quite so clean-cut. At the outset of the war in 1861, the North was caught up in rage militaire, or the fervent need to stand by the stars and stripes in an effort to prove one’s masculinity and patriotism.[4] The unifying nature of rage militaire and the desire to “lick the south”, as Cuddy put it, made it easy to put aside partisan differences for the benefit of preserving the Union.[5] The excitement over the prospect of battle and the optimistic prediction of a swift end to the war as portrayed in Cuddy’s first letter reflect the concept of rage militaire perfectly. Initially, in the eyes of Cuddy and his fellow soldiers, patriotism and hardly anything more was the only reason for wanting to join the fight. But as the war evolved into something more complex, so too did opinions and expectations surrounding how it should have been fought.

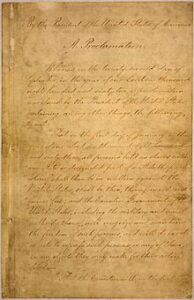

The John Cuddy who wrote home in January of 1863 was a very different man than the one who was so enamored by rage militaire just two short years prior. Clearly worn out from the trials of battle and military life, Cuddy was also clearly grappling with the blow dealt by President Lincoln’s recent Emancipation Proclamation. The proclamation ensured that all enslaved individuals in Confederate territories were irrevocably freed from bondage. Issued on January 1, 1863, the document “elated Northern Republicans, dismayed Northern Democrats, and outraged Southern rebels.”[6] For Union soldiers, however, “contact with African Americans as Union armies moved southward influenced attitudes about slavery and race, building support for emancipation.”[7] Even among those soldiers who were opposed to emancipation as a matter of principle, perhaps due to Democratic loyalty, the necessity of the proclamation as a wartime measure was widely acknowledged. Troops were relieved to find that the war was no longer just a duel between the North and South, but a battle between morality and sin. [8] While those back home were more distinctly divided over the issue of emancipation, the men on the front lines knew that it not only meant that an end to the war may have been on the horizon, but also that they had something more to fight for.

Despite the overwhelmingly- sometimes begrudgingly- positive reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation from the Union Army, John Cuddy did not hold the same optimistic views as his peers. While his words may sound angry, Cuddy’s tone seems more tired when he says “this ware is an auffel thing fighting for ngroes now is a bad thing” and that “Old abe done a bad thing wen he freed all the slaves.”[9] It is certainly possible that Cuddy was wholly opposed to the idea of emancipation, since his hometown of Carlisle housed a great Democratic majority, and support for Lincoln was sparse.[10] However, it is unlikely that Cuddy’s statements were intended to be as malicious as they may come across. After all, he was a young man who went into what he thought would be a swift war with a sense of patriotic duty and high hopes of adventure, only to be met with years of horrific battle. Cuddy said so himself that he was “tiard of ware,” and so he was, in all likelihood, expressing deep frustration over the situation he found himself in.[11] Others in his situation presumably felt news of the proclamation had a relieving effect rather than an aggravating one, and were able to overlook personal prejudices about emancipation in favor of the greater good of repairing the nation. For Cuddy, emancipation exacerbated both his existing prejudices and his resentment towards the war as a whole, which resulted in his unique dissatisfaction towards the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Cuddy was clearly resentful over the longevity of the war and the direction in which its ideological goals appeared to be headed. Not only this, but he was also a man consumed by sorrow and loss. Although crude in phrasing, but nevertheless poignant in meaning, Cuddy asked, “What have we gained by fighting yet we lost more then we ganed[?].”[12] By this point in the war, Cuddy’s unit had lost many of its original men. In the latter part of his letter, he mentioned the need for his division to recruit more men, as they only had 2,500 men remaining at the time of his writing.[13] Not even a year prior to the writing of this 1863 letter, Cuddy lost one of his close friends, William Henderson, to pneumonia, and four of his fellow soldiers to a single cannonball at Antietam just a few months after that.[14] Miserable in the absence of those he loved and mourning the loss of his comrades, Cuddy expressed distaste for the proclamation that did nothing to benefit his immediate situation. The Emancipation Proclamation did nothing for his fallen friends, and it did not bring his family any closer, it only transformed the conflict into something of greater moral substance, and to Cuddy this was not enough.

Modern views of the Civil War tend to focus on its two-sidedness, painting it as a war of right vs. wrong with hardly any sense of nuance. Even during the war, many tended to hold a relatively similar view, with each side essentially wanting revenge for wrongs committed by the other. There is some truth to this notion, as the ideological differences that permeated the Union were largely able to be overlooked in favor of the larger uniting goal of restoring the United States. But, as demonstrated by the case of John Cuddy, putting aside those differences was not as easily done as it may have appeared, especially as the circumstances of the war evolved over time. The Civil War may have had two sides, but it was not strictly two-sided, and there was instead a spectrum of opinions that existed within each faction. Although John Cuddy may be a small exception to the stereotype of the moral, duty-bound Union soldier, he was proof that each side of the Civil War had many sides of their own.

Works Cited:

[1] “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, July 7, 1861,” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, [WEB].

[2] “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, January 16, 1863,” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, [WEB].

[3] “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, January 16, 1863”

[4] Zachery A. Fry, A Republic in the Ranks : Loyalty and Dissent in the Army of the Potomac, (Civil War America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 16, [WEB].

[5] “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, July 7, 1861,”

[6] Louis Masur, The Civil War, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 48.

[7] Gary W. Gallagher, The Union War, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), 80.

[8] Masur, 48.

[9] “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, January 16, 1863,”

[10] “From Carlisle to Andersonville,” House Divided, April 19, 2011, video, [WEB].

[11] “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, January 16, 1863,”

[12] “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, January 16, 1863,”

[13] “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, January 16, 1863,”

[14] “From Carlisle to Andersonville,”