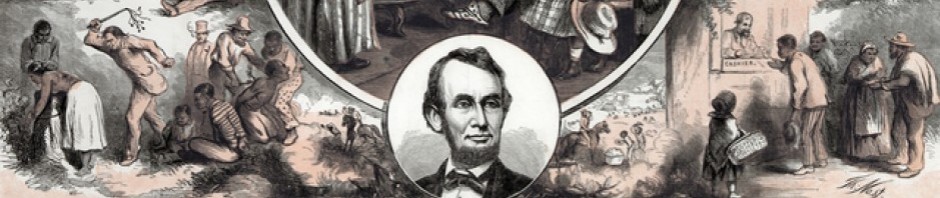

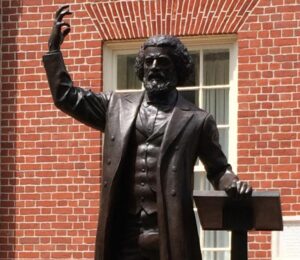

“Few evils are less accessible to the force of reason, or more tenacious of life and power, than a long-standing prejudice.”[1] This powerful quote opened “The Color Line,” an article written by Frederick Douglass in 1881. As a formerly enslaved person later known for his literature and orations focusing on equal rights for Black Americans, Douglass offered numerous insights regarding race relations in America. Throughout the Reconstruction Era, as some in the politically reunified country attempted to reconcile the horrific cost of slavery on human lives, Douglass asserted himself as a scholar on the topics of enslavement and the prejudice that came from it. His position in American politics and his autobiographical experiences further contextualized his authorship of “The Color Line” in 1881, including his life as an enslaved man, his complicated relationship with Abraham Lincoln, and his various political roles in the 1870s. Douglass’ article offered an opening in which the impact of slavery was philosophically analyzed through the lens of its past and its anticipated future in the (Re)united States of America. “The Color Line” could be used today to view Douglass’ life through sociological and philosophical lenses in a work that is shorter than his autobiographies, but just as impactful.

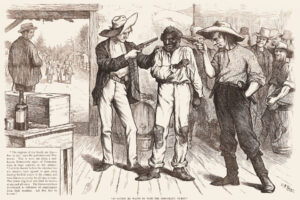

“The Color Line” was published in 1881 in The North American Review, the oldest literary magazine in the United States.[2] The article was eleven pages in length and was presented as an informative text about how the color line came to be and why it was persistent in American society. As presented by Douglass throughout his article, the color line described the social division between Black people and White people in America. This division was created by slavery and continued through the introduction of divisive legislation by Southern state governments, such as poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses in the years following the implementation of the 15th Amendment.[3] In Northern states, the color line was more evident socially in the “widely divergent spheres” of the two races.[4] As a phenomenon that was both old (in the relationship between slaveholders and those enslaved) and new (as a sociolegal development after the Reconstruction Amendments), the color line was an important issue for Douglass to discuss in his article.

In the opening paragraph of “The Color Line,” Douglass discussed the nature of prejudice in society and its lasting impact on those it oppressed. He claimed that “few evils” were as rigid as “long-standing prejudice,” which he argued was a “moral disorder,” that became stronger as it denied arguments against it, especially as it created new, ugly images of Black people in society. Douglass further claimed that it was easy for people “to see repulsive qualities in those we despise and hate,” as prejudice added a new tint to the lenses of oppressors’ vision.[5] In the remainder of the article, Douglass discussed the origins of prejudice in slavery, its effects on the Black race, and its persistence in society. After the first paragraph, he discussed the existence of prejudice in historical England. He claimed that prejudice has existed elsewhere in other forms, but “of all the races and varieties of men which have suffered from this feeling, the colored people of this country have endured the most.” Douglass further argued that prejudice was “unreasoning,” and it made the Black man “the slave of society” even after slavery was abolished in America in 1865.[6]

Even though some claimed that prejudice was “natural, instinctive, and invincible” in society, Douglass argued that if this were true, then it would have been true universally.[7] He claimed that there was “no color prejudice in Europe,” which discredited his first and second caveats of prejudice, and he further argued that most prejudices in America came from the guilt of White people, as they found it easier to oppress those they had harmed, rather than to make reparations for their actions.[8] Additionally, since White people in the South were economically interested in keeping Black people enslaved, they continued to oppress and belittle them. “Out of slavery has come this prejudice and this color line,” Douglass asserted in his article.[9] After he established the origins of the American color line, Douglass claimed that the prejudice in society could not be attributed to merely the color of one’s skin—there must have been an association of skin color with undesirable conditions, such as “slavery, ignorance, stupidity, servility, poverty, [and] dependence.”[10] Douglass claimed that this color line must have been man-made, for it was too inconsistent to be natural. One example of this inconsistency was the way White men feared the rise of the Black race, yet they claimed Black people were “originally and permanently inferior.”[11]

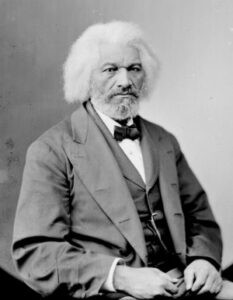

In his closing paragraph, Douglass asserted his belief in great men to overcome the effects of prejudice. “Men who are really great,” he wrote, “are too great to be small,” and he included Abraham Lincoln amongst others in his subsequent list of great men he knew.[12] In an optimistic outlook, Douglass stated that “the number of those who rise superior to prejudice is great and increasing,” but he still envisioned a nation in which all people “respect[ed] the rights and dignity” of each other. As seen in his first paragraph, he ultimately knew that prejudice would be difficult to rid the country of.[13] The descriptions of discrimination in “The Color Line” were likely an attempted appeal to members of the public who supported the abolition of slavery during the Civil War, as it would have been in their ability to perhaps open the eyes of those who denounced equal rights. Additionally, when he wrote this article, Douglass was focused on an updated version of his autobiography, which may have contributed to his philosophical views regarding experiences with prejudice.

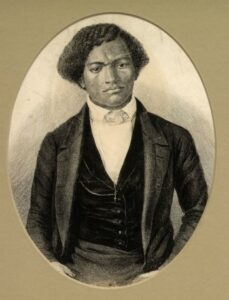

Douglass was born in the Eastern Shore region of Maryland in 1818 as an enslaved man, and at the age of eight, he was hired out by his master and relocated to Baltimore, where he taught himself how to read and write. At the age of fifteen, he was sent back to the Eastern Shore, where he taught other enslaved people and eventually attempted to escape. He was then returned to Baltimore where he met Anna Murray, a free Black woman. Murray helped Douglass escape by providing him with money for a train ticket, which he boarded under disguise and rode to New York City, where he declared himself free. In New York, he married Anna, and they moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts after they decided it would not be safe for Douglass to live in the city as a fugitive. In Massachusetts, Douglass attended abolitionist meetings and spoke about his experiences as a slave, and he soon began to work as an agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. To prevent himself from being captured and enslaved again, Douglass traveled overseas to Europe where he gave speeches about emancipation and sold copies of his first autobiography. After abolitionists in Europe offered to purchase his freedom, Douglass returned to America as a free man. He and Anna relocated to Rochester, New York, where he started a newspaper, The North Star.[14]

When the Civil War began in 1861, Douglass worked to ensure that emancipation would be a result. He continued to speak about his experiences, and he even denounced President Abraham Lincoln’s inaction on slavery at the beginning of the war.[15] After the Emancipation Proclamation was presented on January 1, 1863, Douglass worked to recruit Black soldiers to join the war effort. He believed that serving in the army would guarantee them citizenship after the war ended.[16] During the war, Douglass also met with Lincoln to advocate on the behalf of Black soldiers who were not receiving equal treatment to White soldiers.[17] The relationship between Douglass and Lincoln was historically complicated, as the orator was oftentimes frustrated with the president, but eventually praised his character and decision-making. This was particularly evident in “The Color Line,” when Douglass mentioned him as a man “too great to be small.”[18] Douglass’ work during the Civil War exhibited his desire for Black representation and equality in the nation, and it additionally helped him gain standing in the Republican Party, which he became closely aligned with in the following years.[19]

In 1872, the Douglass family moved to Washington D.C. where Frederick held several office positions before the election of President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, “including assistant secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission, legislative council member of the D.C. Territorial Government, board member of Howard University, and president of the Freedman’s Bank.” Later, between 1877 and 1891, Douglass served under five presidents at three different positions.[20] After serving as the U.S. Marshall for Washington D.C. under President Hayes from 1877 until the change of administration in 1881, Douglass was appointed as the Recorder of Deeds for Washington D.C. under President James A. Garfield.[21] This less-involved position frustrated Douglass, which could have contributed to his thoughts on the prejudice he saw and felt as a Black politician in America. Throughout his political career, Douglass aligned himself with the Republican Party, although he presented his ideas during and after the Civil War as typically radical.[22] It was during these years in his political career that Douglass published “The Color Line.” Additionally, over the course of his life, Douglass produced three autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass in 1845, My Bondage My Freedom in 1855, and Life and Times in 1881.[23]

When “The Color Line” was published in 1881, Black people were beginning to experience the oppression and racism of the Jim Crow Era in the American South.[24] The Reconstruction Amendments—including the 13th in 1865, the 14th in 1868, and the 15th in 1870—had appeared to offer legislative protection to those of African descent, but they were quickly circumvented by legislators repulsed by racial equality.[25] Through the implementation of poll taxes, residency requirements, grandfather clauses, literacy tests, and other discriminatory regulations, Black people were largely prevented from exercising their constitutional right to vote in the South from the 1870s until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.[26] During a campaign address for President Garfield in 1880, Douglass spoke about the nullification of the Reconstruction Amendments by the South, and this racist legislation was likely at the forefront of his mind when writing his article in 1881.[27] In “The Color Line,” Douglass presented readers with an explanation for the persistence of prejudice in society as seen in the regulations preventing the Black vote. He alerted his audience that because of the characteristics of prejudice, it could survive and thrive in post-Civil War American society for years to come.

In the election of 1880, Douglass campaigned for Republican candidate James Garfield, but his role was less important than it had been during the two previous administrations. As “a new generation of black leaders” came into the political realm, Douglass was slowly pushed out.[28] This new generation was mentioned in the last paragraph of Douglass’ article when he referred to numbers growing of people “who rise superior to prejudice.”[29] When Garfield was elected in 1880, Douglass hoped for another presidential appointment to a position of importance, even though internally he was only waveringly faithful to the new Administration. Instead, he received what he saw as a demotion to the Recorder of Deeds for Washington D.C., which likely left a bitter impression with prejudice on his mind. Around the publishing of “The Color Line” in 1881, Douglass also completed an updated version of his autobiography titled Life and Times, in which he reflected heavily on his experiences with great men and sought to define “the theory of the American self-made man.”[30] As Douglass reflected on his life while writing this third autobiography and “The Color Line,” he must have also considered his various encounters with prejudice.

Even though the Reconstruction Era ended in 1877, Douglass believed that White Americans still had to evolve in their thoughts and actions towards other races. By claiming there are “few evils” that act in the same ways as prejudice, he asserted that racial discrimination was one of the worst societal diseases man could experience.[31] This was perhaps the mindset of someone tired of people with the same skin color as him being treated with such hatred. This prejudice “refus[ed] all contradiction,” namely from Southern legislators and White supremacists, which allowed it to “[distort] the features of the fancied original” and render the voice of the Black man silent.[32] Furthermore, because it “create[d] the conditions necessary to its own existence,” Douglass believed that prejudice would continue to affect Black lives in the future. By hating Black people for more than merely the color of their skin and associating the entire race with undesirable qualities—as discussed by Douglass in the rest of his article—the White race was (and will continue to be) consistently oppressive to People of Color.[33]

In the opening paragraph of “The Color Line,” Douglass described the prejudice that had taken hold of American society during and after the abolition of slavery. He claimed this prejudice would continue to affect the lives of Black people in the future, such as the implementation of discriminatory legislation following the Reconstruction Amendments that affected Black people at the ballot boxes. Douglass’ multiple careers during the initial years of these Jim Crow laws further allowed him to effectively analyze the philosophy of this prejudice through his growing disappointment with American politics.

Today, “The Color Line” may seem to be one of Douglass’ more insignificant works, especially in the wake of his speech in 1876 at the Emancipation Memorial in Washington D.C., proceeding his reflections on the Lost Cause in 1883, or when he published three separate autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass in 1845, My Bondage My Freedom in 1855, and Life and Times in 1881.[34] Despite these other, more famous works by Douglass, “The Color Line” can serve several purposes when analyzed fully. Although it is not directly an autobiographical work, it reflects many of Douglass’ experiences as an enslaved man, a writer, an orator, an abolitionist, a war-time recruiter, and a politician. This article could therefore be used to peer into Douglass’ life through sociological and philosophical lenses, especially since it is much shorter and easier to sift through than a full autobiography. By incorporating explanations for the history of prejudice into “The Color Line,” Douglass provided a glimpse into the possible future of race relations in American society.

[1] Frederick Douglass, “The Color Line,” The North American Review, University of Northern Iowa, vol. 132, no. 295 (June 1881), 567, [WEB].

[2] Author Unknown, North American Review, University of Northern Iowa, 2021, Accessed Dec. 6, 2021, [WEB].

[3] Farrell Evans, “How Jim Crow-Era Laws Suppressed the African American Vote for Generations,” History, May 13, 2021, Accessed Dec. 9, 2021, [WEB].

[4] John Mecklin, “The Philosophy of the Color Line, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 19, no. 3 (Nov. 1913), 354, [WEB].

[5] Douglass, “The Color Line,” 567. [6] 568. [7] 569. [8] 571. [9] 573. [10] 575. [11] 576. [12] 577. [13] 577.

[14] Author Unknown, “Frederick Douglass,” National Park Service, July 24, 2021, Accessed Dec. 6, 2021, [WEB].

[15] Louis P. Masur, The Civil War, (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011), 41.

[16] Masur, 56-57.

[17] Author Unknown, “Frederick Douglass.”

[18] David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 337: Author Unknown, “Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln: Frederick Douglass (1818-1895)” from The Lincoln Anthology: Great Writers on His Life and Legacy from 1860 to Now, Library of America, Feb. 9, 2013, Accessed Dec. 10, 2021, [WEB]: Douglass, “The Color Line,” 577.

[19] Roy E. Finkenbine, “Douglass, Frederick,” American National Biography, February 2000, Accessed Dec. 8, 2021, [WEB].

[20] Author Unknown, “Frederick Douglass,” National Park Service, July 24, 2021, Accessed Dec. 6, 2021, [WEB].

[21] Noelle Trent, “Frederick Douglass,” Britannica, Oct. 5, 2021, Accessed Dec. 11, 2021, [WEB].

[22] Louis P. Masur, The Civil War, (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011), 41.

[23] William L. Andrews, “African American Literature,” Britannica, Jul. 28, 2020, Accessed Dec. 12, 2021, [WEB].

[24] Evans, “How Jim Crow-Era Laws Suppressed.”

[25] Author Unknown, “The Reconstruction Amendments,” National Constitution Center, Accessed Dec. 13, 2021, [WEB].

[26] Evans, “How Jim Crow-Era Laws Suppressed.”

[27] Blight, Frederick Douglass, 616.

[28] Blight, Frederick Douglass, 612.

[29] Douglass, “The Color Line,” 577.

[30] Blight, Frederick Douglass, 615, 619.

[31] Douglass, “The Color Line,” 567. [32] 567. [33] 571.

[34] Anna Maria Gillis, “Frederick Douglass Lived Another Fifty Years After Publishing His First Autobiography,” Humanities, vol. 38, no. 1 (2017), from National Endowment for the Humanities, Accessed Dec. 12, 2021, [WEB]: Andrews, “African American Literature.”