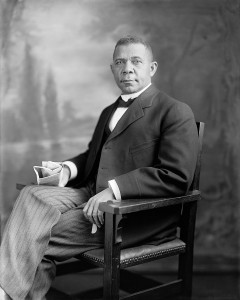

Themes of Republicanism in Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery

Despite declaring that his life began in the “most miserable, desolate, and discouraging surroundings,”[i] Booker T. Washington’s narrative, Up From Slavery, is brimming with republican optimism and perseverance. Based on Washington’s narrative, after departing from the abhorrent institution of slavery, blacks had inherited republic ideals and aspects of Southern culture that defined their lives even after gaining their freedom.

Even while still enslaved in a Virginian plantation, Washington’s hunger for education was insatiable. After witnessing one of his mistresses attending school at a local schoolhouse, Douglas resolves that one day he will seek an education for himself. Republicanism placed a heavy weight on the value of education, which was seen as a deterrent for tyranny.[ii] As such, even nearly a decade after the founding of the Republic, men and women alike still attended school for the hopes of contributing to the virtuous republic through education; this desire for education was not lost on the slaves who observed this culture of seeking virtue through education.

However, education was not something that was readily available to blacks. Even after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freed slaves were in a significantly disadvantaged position. Despite the promises freedom held, it also came with an independence that had not previously existed under the rule of a master. On this matter, Washington wrote, “In a few hours the great questions with which the Anglo-Saxon race had been grappling for centuries had been thrown upon these people to be solved. These were the questions of a home, a living, the rearing of children, education, citizenship, and the establishment and support of churches.”[iii]

However, this socioeconomic disadvantage did not impede the perseverance and progress of blacks like Washington. Staying true to the republican ideal of upward mobility and the “self-made man,”[iv] Washington begins work in a salt mine operating in Malden, West Virginia. While working, Washington finds himself in a culture that operates largely outside of social institutions, and which therefore adopts a lifestyle of roughness which Washington equates to immorality– “Drinking, gambling, quarrels, fights, and shockingly immoral practices were frequent.”[v] The practices that Washington describes are likely similar, if not identical, to the rough leisure activities practiced by whites that lived in backcountry areas similar to the black community in which Washington found in Malden, WV. These practices adopted by poor residents of isolated backcountry localities were an exercise which prepared its practitioners for “a violent social life in which the exploitation of labor, the specter of poverty, and a fierce struggle for status were daily realities.”[vi]

Although these practices were common among poor, back country blacks, there were groups of newly freed slaves, one of which was Washington, who desired a culture of education and earnestness. While working in the salt mines, Washington managed to acquire one of a copy of Webster’s Blue Back Speller, a book that had burgeoned in popularity after the Revolutionary war, selling around 3 million copies by 1783[vii]. Nearly a century later, the book still provided a means of education to members of the republic seeking an education. Determined to receive a formal, higher education, Washington used the money he saved from working in the salt mines to attend the Hampton Institute. Having “resolved to let no obstacle prevent [him] from putting forth the highest effort” to seeking an education and giving to his community, Washington earns his keep at Hampton by proving his worth as a skilled janitor. Washington explains his reasoning behind his eagerness to earn his keep through labor, something which he noted that other freed slaves had chosen to give up for good; Washington knew that education was inseparable from labor and he valued labor for “labour’s own sake and for the independence and self-reliance which the ability to do something which the world wants done brings.”[viii] In describing his time at Hampton, Washington’s narrative is rich with the republican ideals of removing paternalistic and dependent relationships from the country and instead cultivating a culture of independence and individual liberty.[ix]

Even after the immediacy of his emancipation, Washington continued to play the role of the ideal citizen of the republic by seeking an educated and virtuous life. Despite having little to give other than his time, effort, and knowledge, Washington became philanthropist by supporting initiatives to educate native Americans and fellow blacks at the Hampton Institute and the Tuskegee Institute, respectively. Washington’s greatest legacy is arguably the Tuskegee Institute, a facility aimed towards instilling the republican qualities of earnestness, virtue, and appreciation of labor in the less fortunate, albeit freed, blacks of the South.[x]

[i] Booker T. Washington, Up From Slavery: An Autobiography (New York: Skyhorse, 2015), 12.

[ii] Gordon S Wood, The American Revolution (New York: Modern Library, 2002), 122.

[iii] Washington, Up From Slavery: An Autobiography, 28.

[iv] Wood, The American Revolution, 121.

[v] Washington, Up From Slavery: An Autobiography, 32.

[vi] Elliot J. Gorn, “‘Gouge and Bite, Pull Hair and Scratch’: The Social Significance of Fighting in the Southern Backcountry,” The American Historical Review 90 (1985): 22, accessed August 29, 2009.

[vii] Wood, The American Revolution, 124.

[viii] Washington, Up From Slavery: An Autobiography, 68.

[ix] Wood, The American Revolution, 125.

[x] Emma Lou Thornbrough, Booker T. Washington (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1969), 37.