In the early 1840’s slavery in the South was thriving and millions were trapped in its horrific way of

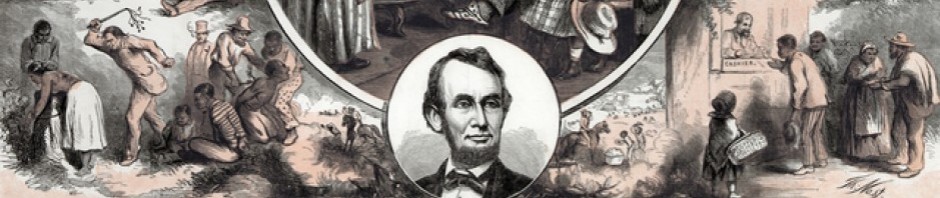

life. One married couple, having endured lives of slavery, decided this wasn’t the way they wanted to live, a decision that would lead to a long journey for freedom. This couple was William and Ellen Craft. William was the son of two slaves from Macon, Georgia, a small city in the center of the state. At an early age his family was split up, after his master sold his parents, a brother, and a sister to separate owners. William was sent out to work as an apprentice for a cabinetmaker, a job that would earn him little money for his work. At the age of sixteen, William’s master took out a mortgage to help expand his farm and cotton business. However, when repayment was due, the master was without the proper funds, and the bank took William and his younger sister as compensation. William was sold to the cashier at the bank in Macon, and he allowed to continue working at the cabinet shop. His sister, however, wasn’t so lucky and she sold off to a farmer far away. A few years later, his wife, Ellen, moved to Macon with her owners family, and she worked as a house servant. Ellen was born in Clinton, Georgia and was the daughter to her master, Major James Smith. She was given away as a wedding gift by the master’s wife as a way of getting rid of the evidence of her husbands infidelity. The master’s wife often became upset when guests would mistake Ellen as one of her children due to her fair complexion.

In Macon, William and Ellen met and immediately fell in love. Ellen wouldn’t marry William at first because she didn’t want to start a family in slavery–remembering the pain of her mother they were separated. Eventfully, after coming to the conclusion they would be enslaved for the rest of their lives, they got married. After living in slavery as a married couple for two years, they decided to start a family. However, they also wanted their freedom. They knew that they only had one option, to escape to the North.

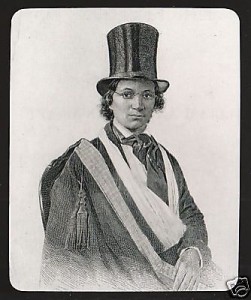

In order to escape, Ellen had to pretend that William was her slave, and that she was travelling with him as his owner. They would use this disguise in order to travel to Philadelphia, in the free state of Pennsylvania. Because of Ellen’s fair skin tone, it would be easy to pass her off as white. However, in the South it wasn’t customary for a white woman to be traveling alone with a male slave, and this would bring a lot of unneeded attention to the couple. For this plan to work, Ellen realized that she would have to dress up as a man. In the days before the escape, William went out to buy men’s clothing for Ellen to wear. He would have to shop at odd hours of the day because, in Georgia, it was illegal for whites to trade with slaves without the permission of their master. However, many shop owners would still sell to slaves for the money and if no one was around. After they collected all the pieces of clothing, they then asked their masters for some time off. After their requests for leave were granted, the couple were sure that the few days off would allow them to get a head start on their escape and create some space between them and their masters before they realized that they were trying to escape. During Christmas time it wasn’t uncommon for slaves to ask their masters for a few days off to be at home with their families. When the day of the escape arrived, Ellen got into her disguise and the Craft’s set off to the train station. They took the train from Macon to their first destination, Savannah, Georgia. After getting their tickets Ellen sat in the white-only train-car, while William sat in the colored car. While sitting against the window, Ellen was approached by a man, a good friend her owner, and he sat next to her. The man tried to start a conversation with Ellen but she ignored him, hoping not to give herself up. Resulting from her silence, a nearby man suggested that maybe she, or rather “he,” was deaf, causing the man to leave her alone. When they arrived in Savannah, the Craft’s boarded a steamboat to Charleston, South Carolina, their next stop. On the boat, Ellen made conversation with a military officer who was also traveling with a slave. The military officer was shocked by how nice Ellen was to her slave, and called in his slave to show how they were supposed to be treated. “You will excuse me, Sir, for saying I think you are very likely to spoil your boy by saying ‘thank you’ to him. I assure you, sir, nothing spoils a slave so soon as saying, ‘thank you’ and ‘if you please’ to him.”(Craft 50)[1]

When they arrived in Charleston Ellen and William got a room at a nice hotel where other slaves were also working. Here, William would strike up a conversation with these slaves who became very emotional when talking about their life in slavery and their freedom.”Gorra Mighty, dem is de parts for Pompey; and I hope when you get dare you will stay, and nebber follow dat buckra back to dis hot quarter no more, let him be eber so good.”(Craft 54) [2] The next day, they boarded a steamboat to Wilmington, North Carolina, however, before boarding, they first had to get by the Customs- House in Charleston. It was here that travelers had to sign their name and with whom they were travelling into the customs book. Ellen, being a slave, could not write and faked an injury to her hand so that someone else would have to sign her signature. At first the plan backfired, as the officer inside the customs house refused to sign Ellen’s name. However, the situation was quickly defused when the military officer who Ellen had conversed with before stepped up to say that he knew the her, or rather “him”. The captain of the steamboat overheard the conversation and signed the book for Ellen. This allowed the Craft’s to advance in their journey. They would then travel from Wilmington, North Carolina to Richmond, Virginia to Washington, D.C. and then to Baltimore without any incident. Baltimore would be their last stop in a slave state and their final obstacle before entering freedom. They were set to leave Baltimore on Christmas Eve of the year 1848. At the train station they ran into trouble when a man pulled William off the train and demanded to see his master to show proof of documentation for Northern travel. Just when the couple thought their plan was ruined, the conductor of the train told the officers that he had been with them since Washington, D.C., and the officers at the station then let them board the train. The Craft’s would finally reach Philadelphia and their freedom the next day, on Christmas.

Soon after arriving in the city the Craft’s made friends with a man named Robert Purves who was a wealthy business man from Philadelphia. He introduced the Craft’s to another man named Barkley Ivens, a farmer from the countryside. Mr. Ivens invited the Crafts over for dinner one night where they met his daughters. During dinner, over conversation, the Craft’s revealed that they could not read nor write. The daughters jumped at this opportunity and began giving the two lessons, beginning with how to sign their names. In 1829, a law passed in Georgia that banned slaves from learning how to read and write.[3] This law was similar to those in southern states at the time. Learning how to sign their names was important to the Craft’s, because it allowed them to sign their names on things such as important documents, a true symbol of their freedom.

The Craft’s only made Philadelphia home for a short time, after being advised to leave the city by other abolitionists. While Pennsylvania was a free state, racial tensions were ever growing. Being on the border of the Mason-Dixon line meant that Pennsylvania was the first place that runaway slaves were stopped when coming up from the south. With the influx of people within the city of Philadelphia, came an increase in crime rates. The judicial system also showed prejudice against African Americans, as a their sentences was usually much harsher than a white man’s when they had committed the same crime.[4] This lead to a negative stigma about African Americans and would often lead to racial hate crimes.

The abolitionists suggested that the Craft’s move up Boston where the community is much more tolerant of colored people. The Craft’s obliged and made Boston their home for the next two years until 1850, when the Fugitive Slave Act was passed by congress. The Fugitive Slave Act allowed masters to go after the runaway slaves who had already escaped into free territories. The Craft’s learned that their former master sent agents to find and return the two to Macon. Upon hearing this, the Craft’s knew that they were no longer safe anywhere in the U.S., and decided that it would be best to move to England to ensure their safety. With the help of some friends, the Craft’s eluded the slave catchers to begin their journey to Liverpool, England. There, the Crafts fulfilled the promise they made from the beginning which was to have children who were born free. In 1870, the Craft’s returned to the United States, and decided buy a farm outside of Savannah, Georgia. A few years later, the Craft’s, with the help of some investors, opened the Woodville Co-Operative Farm School where they taught and employed former slaves. The school was short-lived because the funds to run the school ran out by 1876. After this, the Craft’s retired to a quiet life, and lived out their days with their daughter in Charleston. [5]

[1] William Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or, the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery, (London 1860). 50.

[2] William Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or, the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery, (London 1860). 54.