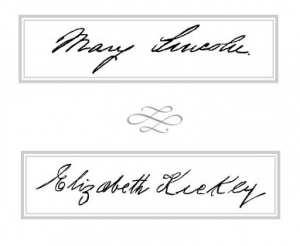

Elizabeth Keckly’s story is a remarkable one. Her life is important to discuss when analyzing the act of manumission, which is when a slaveholder decides to free their own slaves. Elizabeth Keckly was a loyal slave for many years to master Colonel A. Burwell [1]. Her fidelity in service to her slaveowners was recognized and honored through Lizzy Keckly and her son’s liberation. The spelling of her name speaks to her strength and her ability to find independence and individuality in a life that was oppressive in its majority. Elizabeth Keckly spelled her name differently than how it appears in history books and most published articles, and how even Abraham Lincoln’s wife spelt it [2]. “Lizzie Keckley” is the spelling most commonly seen. However, she herself would sign her name “Elizabeth” or “Lizzy Keckly.” Thus in this blog post, much like Jennifer Fleischner’s book, Elizabeth’s name will be spelt as “Lizzy Keckly” in order to restore her voice in history and present Lizzy how she presented herself [3].

The reasons for a slaveholder to decide to free his or her slaves varied upon the owner [4]. In some cases, slaveholders exercised the act of manumission because a slave had surpassed a capable age to effectively execute the labor that needed to be completed on the plantations and were no longer of best use to their slave owners [5]. In other cases, similar to Keckly’s situation, freedom was granted due to loyalty, service, or good behavior. Originally, when Keckly asked her master for freedom, he refused [6]. Her motive for requesting liberation was because she did not want her son to be born into slavery like she was [7]. Keckly’s son “came into the world by no will” of her own [8]. “One-half of my boy was free, and why should not this fair birthright of freedom remove the curse from the other half… Much as I respected the authority of my master, I could not remain silent on a subject that so nearly concerned me” [9]. Her son was of mixed-race, however Keckly did not want her son to live a mixed-life; she wanted him to only know freedom [10].

Sexual relations between masters and slaves was common This created a population of slaves that had become “visibly whiter” [11]. It is possible that due to this relationship that her master felt guilty about owning one of his own children. However, this is not explicitly indicated. According to her memoir, it was Keckly’s loyalty and servitude to the her masters for decades that explained why her owner eventually decided to liberate Keckly and their son. She was strategic with her requests for freedom. When her master told her he would pay for her to run away and take the ferryboat, she refused by showing loyalty in this moment [12]. In addition, she stated that she wanted to earn the money to buy her and her son’s freedom, which attests to her pragmatism, drive, and level-headedness in obtaining the “upward mobility” she sought [13]. She was able to borrow, and repay through dressmaking, $1,200 in exchange for her and her son’s freedom. That amount of money is equivalent to about $27,000 today [14].

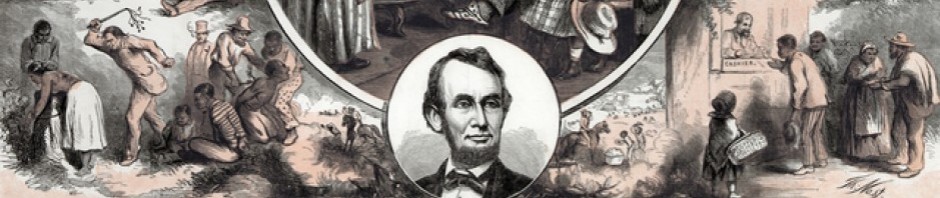

Her life is the story of a woman who did not back down; she persevered for years and eventually became a freed woman, a successful businesswoman, and even became a close confidant to Abraham Lincoln’s wife [15]. Even through all of the years of torture and both mental and physical brutality, Lizzy Keckly was resilient and held onto the belief that “it will be all silver in heaven” [16]. Her experience with Mr. Bingham specifically speaks to her strength and resilience; “she did not scream; she was too proud to let her tormentor know that she was suffering” [17]. Keckly demanded to her master as to know why she had been “flogged” and beaten by Mr. Bringham, who was not even her own master. When she stood up to Mr. Burwell’s son during this demand, she experienced more torture. However, this did not break Keckly, but rather made her stronger. By the third time Mr. Bingham “flogged” her, he was the one to break down, cry, and ask for forgiveness. Keckly’s perseverance through these brutal ordeals helped future slaves that came across Mr. Bingham or were owned by him as it is believed that after this last incident, Mr. Bingham never abused another slave again [18].

Keckly was unlike most slaves as she stood up for herself. Even if she was afraid, she did not let her fear of punishment get in the way of what she wanted to know or what she wanted to accomplish. Many slaves were unsuccessful in their attempts to be granted manumission [19]. In some cases, slaveholders would pass away before being able to fulfill their manumission and liberation agreements. In other cases, some slaveholders would simply fall through on their deals; it varied on the slaveowner [20]. However, Lizzy Keckly’s loyalty, pragmatism, and optimism for a brighter future allowed her to persevere and obtain freedom for herself and her son. Due to her loyalty and her resilience, she lived a unique and remarkable life and died in 1907 as a free woman [21].

[1] Keckley, Elizabeth, Behind the Scenes, or Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (1868, republished 1988).

[2] Jennifer Fleischner, Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship Between a First Lady and a Former Slave (New York: Broadway Books, 2003), 4.

[3] Fleischner, 4.

[4] A bond for the manumission of a slave, 1757, The Gilder Lehman Institute of American History. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/origins-slavery/resources/bond-for-manumission-slave-1757.

[5] A bond for the manumission of a slave, 1757.

[6] Keckley Elizabeth, 46.

[7] Keckley Elizabeth, 47.

[8] Keckley Elizabeth, 47.

[9] Keckley Elizabeth, 48.

[10] Fleischner, 4-5.

[11] Fleischner, 5-6.

[12] Keckley Elizabeth, 48.

[13] Fleischner, 6-7.

[14] “A Slave’s Life,” EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2007); Keckley Elizabeth, 49; McNally, Deborah. “Keckley, Elizabeth Hobbs (1818-1907).” Blackpast.org Blog. Accessed November 07, 2016. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/keckley-elizabeth-hobbs-1818-1907.

[15] “A Slave’s Life,” EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2007).

[16] Keckley Elizabeth, 3.

[17] Keckley Elizabeth, 31-37.

[18] Keckley Elizabeth, 31-37; “Keckley, Elizabeth Hobbs (1818-1907).” Blackpast.org Blog. Accessed November 07, 2016. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/keckley-elizabeth-hobbs-1818-1907.

[19] Rowe, Linda. “Manumission takes careful planning and plenty of savvy.” (Williamsburg: Interpreter, 2004). http://www.history.org/history/teaching/enewsletter/volume3/february05/manumission.cfm.

[20] Rowe, Linda. “Manumission takes careful planning and plenty of savvy.” (Williamsburg: Interpreter, 2004). http://www.history.org/history/teaching/enewsletter/volume3/february05/manumission.cfm.

[21] “A Slave’s Life,” EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2007); “Keckley, Elizabeth Hobbs (1818-1907).” Blackpast.org Blog. Accessed November 07, 2016. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/keckley-elizabeth-hobbs-1818-1907.