BOLD TEXT, NOT INCLUDING SECTION HEADERS, REFER TO MAP MARKERS

Introduction

General Buford (Courtesy of Civil War Cavalry)

James McPherson, historian and author of several books including The Battle Cry of Freedom, stated that “Gettysburg proved a significant turning point in the war, and therefore in the preservation of the United States and abolition of slavery”. His statement is well founded, as General Meade’s Union Army of the Potomac was able to inflict disastrous losses on General Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia that could not be replaced due to Southern manpower shortages. Yet on many occasions over the three day battle, Confederate troops came close to victory; however, aside from acts of valor by Union troops, there were several factors that contributed to Confederate defeat: poor reconnaissance and communication, strong Union defensive positions, poor and insufficient equipment, and strategic errors on the part of General Lee.

The First Day of Battle On June 30th, 1863, Confederate troops under General J. Johnston Pettigrew moved towards the town of Gettysburg in search of supplies. It was not long before Pettigrew spotted Union cavalry south of the town, causing him to pull out and report to his superiors: General Harry Heth and General A. P. Hill. Although the threat was believed to be local militia, on the morning of July 1st Heth sent his division, accompanied by General Pender’s, into Gettysburg to perform a reconnaissance in force; it was not long before they encountered Union troops entrenched along McPherson’s Ridge northeast of Gettysburg. The “local militia” that Pettigrew had encountered the day before was in fact Union cavalry; an entire division under the command of General John Buford. Having spotted the Confederates the day before, Buford had ordered his cavalry to dismount and set up a defense along McPherson’s Ridge where they hoped to stall the advancing rebel army until Union regulars could arrive. At 7:30am on July 1st, 1863, the first shot was fired, marking the beginning of the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War.[1]

General Reynolds (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

For several hours Buford’s cavalry held the advancing Confederates at bay. In fact, Buford stated that one of his brigades under Colonel Gamble “had to be literally dragged back a few hundred yards to a position more secure and better sheltered.”[2] Finally, at around 10am, General Reynolds, commander of the 1st Corp of the Union Army of the Potomac, arrived on the scene and his corps soon followed. After a short briefing session with Buford, he began deploying his men, taking up positions starting on the Southwestern end of McPherson’s Ridge, extending Northeast across the Chambersburg Pike along McPherson’s Ridge and onto Oak Ridge, and then East to Barlow’s Knoll along the western bank of Rock Creek. Sadly, while ordering the attack of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry Regiment, General Reynolds was shot and killed by a sharpshooter as he was shouting to his troops: “Forward men, forward for God’s sake, and drive those fellows out of the woods!” As he turned to look back, the sharpshooter’s round struck him in the back of the head, killing him instantly.[3]

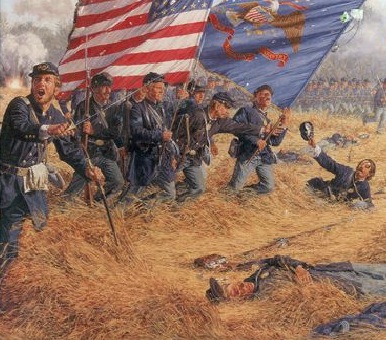

Despite the death of General Reynolds, the 1st Corps and Buford’s cavalry had managed to temporarily hold the Confederates at bay, even successfully counterattacking in the case of Rufus Dawes’ 6th Wisconsin Regiment.[4]

Dawes at the Railroad Cut (Courtesy of Padre Steve’s World)

During a half-hour lull in the fighting from 11:30am to 12pm, the Confederates were able to bring of reinforcements, which included the rest of General Heth’s division, a second division from A. P. Hill’s Corps, under General Pender, and two divisions from General Ewell’s 2nd Corps; Heth’s remaining brigades and general Pender’s division reinforced Heth to the Northwest of Union positions and Ewell’s divisions arrived from Carlisle to the North. The Union Army too had brought up reinforcements, but not enough to match the Confederate numbers; the remainder of Reynold’s (now Doubleday’s) 1st Corps and two divisions of General Howard’s 11th Corps were all that arrived in time to face the resumption of the Confederate assault.[5]

At 1400 hostilities resumed as Confederate troops made attacks all along the Union front line. Unfortunately, General Barlow of the Union 11th Corps had positioned his troops on what is now known as Barlow’s Knoll, creating a salient, or bulge, on the right flank of the Union line which opened the position up to attack from multiple directions.[6] Barlow’s division soon crumpled and Early’s troops, who had engaged the Union right, soon began to roll up the Union lines.[7] As the right flank collapsed, Confederate troops broke through Union positions on McPherson’s Ridge.[8] These two events caused a general collapse of the Union front line, leading to a full scale retreat to Cemetery Hill to the southeast of Gettysburg. Upon arrival, General Hancock took command of the Union troops had that escaped the rebel onslaught, famously noting that the positions the Union now occupied were, “…the strongest position by nature on which to fight a battle that I ever saw.”[9] The next several days would prove him right.

The Second Day of Battle During the night of July 1st and the morning of July 2nd, General Meade, commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, positioned his troops in a fishhook shape, which extended south of Cemetery Hill along Cemetery Ridge, and east to Culp’s Hill where it then turned south again to Spangler’s Spring; Confederate positions mirrored Union lines to their northwest.[July 2nd: Blue Lines] Early on July 2nd, the Union 3rd Corps, under General Sickles, was assigned positions anchored on the right of Cemetery Ridge and running south down to Little Round Top. Seeing elevated ground to his front, Sickles made one of the most controversial decisions of the entire war; against the orders of General Meade, Sickles advanced his Corps forward to positions spanning from the wheat field south and slightly east to Devil’s Den.[July 2nd, Union Troops Under Sickles] Sickles’ justification for his advance was that Confederate occupation of this ground would have made his originally assigned positions untenable, but his advance left his Corps overextended and forming a salient, just as Barlow’s division had on July 1st.[10]

In Sickles’ defense, his advance caught Confederate General Longstreet completely off guard. Due to the absence of General J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry, the army’s primary reconnaissance force, the Confederates had no idea Union troops had been positioned anywhere further south than Cemetery Ridge. Longstreet’s men were the first to learn of the arrival of Sickles’ 3rd Corps, and thus Longstreet was forced to extend his line further south to Warfield Ridge[11] [July 2nd, Confederate Troops under Hood and McLaws]; his attacks were delayed until 4pm that afternoon.[12] Not only was Longstreet delayed, but Sickles’ positions, although not as strong as those originally assigned to him, were quite formidable. Not only were Sickles’ troops positioned on elevated ground, but the terrain, especially around Devil’s Den and Little Round Top, was incredibly rocky which severely hampered the attacker’s movement and provided the defenders with ample cover. Longstreet’s assault began with General Hood’s division hitting Union positions at

Confederate Sharpshooter at Devil’s Den (Coutesy of HistoryNet)

Devil’s Den and attempting to flank around Union lines via the currently undefended Little Round Top. The fighting for Devil’s Den was fierce as Union troops under Brigadier General J. H. Hobart Ward attempted to halt the Confederate advance with the assistance of an artillery battery, but they were eventually overwhelmed. After being driven out of Devil’s Den, Ward’s men briefly tried to make a stand in the valley between Devil’s Den and Little Round Top (known as the Valley of Death), but his brigade was soon sent into full retreat (Ward refers to Little Round Top as Sugar Loaf Hill in his report).[13]

Having pushed Union troops out of Devil’s Den the Confederates now faced an ever more treacherous obstacle: Little Round Top. Having fought hard to take the elevated and rocky position of Devil’s Den, the Confederates now had to descend down into a small, open valley and assault a hill that was taller, steeper and just as rocky; however, until recently, Little Round Top had been undefended. Had word of Sickles’ predicament had not reached General Sykes, commander of the Union 5th Corps, all may have been lost for the Union that day. Upon hearing of the situation, Sykes dispatched his 1st Division to aid Sickles. The first person to see the message was Colonel Strong Vincent of the 3rd Brigade, who, entirely on his own volition, ordered his men to Little Round Top.[14] Vincent placed most of his regiments on the western slope to meet the Confederate advance from Devil’s Den except for the 20th Maine, under command of LTC Joshua L. Chamberlain, which was ordered to hold the southern slopes of the hill; the extreme left of the Union line. Originally about 1,000 strong, the 20th Maine’s years of service had left it with “28 officers and 358 enlisted men”.[15] Miraculously, with the help of the infamous bayonet charge by the 20th Maine, the Union troops on Little Round Top were able to throw back the Confederate assault, ending hostilities on the left flank of the Union line. Although they barely held, Chamberlain’s depleted regiment fought as many of 3 enemy regiments during the battle, which speaks strongly of Little Round Top’s defensibly.

Fighting at the Wheat Field (Coutesy of Paul’s Voyage)

Over an hour after the start of Hood’s attack (5:30pm), General McLaws began his assault on Union positions in the Wheat Field and Peach Orchard. Union troops were able to hold off initial assaults, but were eventually forced out of both the Peach Orchard and Wheat Field with heavy casualties on both sides. Union troops were driven back across Plum Run, some heading for Cemetery Ridge and others for Little Round Top. The fighting was so heavy, that one Union battery was forced to retreat using a technique called “retire by prolonge”, in which the gun is continuously fired while it is being dragged away.[16] During the retreat, General Sickles’ leg was mangled by a cannonball; it was later amputated and can be seen on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine.[17] Confederate troops eventually advanced as far as the Valley of Death, but were thrown back by a Union counterattack under the command of General Crawford. Unable to hold the ground he gained, Crawford again withdrew to Little Round Top, putting an end to the day’s fighting in that sector at around 1930.[18]

Charge of the 1st Minnesota (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

To the north of McLaws, General Anderson’s division began its attack at 6pm, targeting Sickles’ right flank and Cemetery Ridge. Union troops along the Emittsburg Road, many of whom had already been engaged in the fighting against McLaw’s division, were soon overrun and forced back to Cemetery Ridge. One of Anderson’s brigades, under General Wilcox, almost made it through a gap in the Union line, but the heroic charge of the 262 men of the 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment was able to successfully plug the gap and halt Wilcox’s advance. During the charge, the 1st Minnesota suffered 82% casualties.[19] Like Hood’s and McLaw’s, Anderson’s assault was also halted, and he ordered his men to fall back to Seminary Ridge.[20]

Culp’s Hill (Courtesy of Civil War Talk)

That evening, Confederate troops under General Ewell attacked Union positions on Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill on the northeastern bend of the “fishhook”. Both attacks were unsuccessful, resulting in only mild gains at the base of Culp’s Hill and none on Cemetery Hill.[21] Lee’s choice to keep Ewell’s corps positioned on the right flank of the Union front line is a controversial one, as it could do little good against the formidable Culp’s and Cemetery Hill’s. Many historians believe that Ewell’s men could have been shifted over to assist in the assault on Cemetery Ridge. As the attack there was extremely close to being successful, Ewell’s men would most likely have provided the push necessary to break the Union line; however, Lee’s indecisiveness in regards to Ewell’s Corps left it sitting on the Union right flank, where it remained for the rest of the battle, being of little use to the Confederate cause. In Lee’s defense, the absence of J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry left him fairly clueless as to the exact whereabouts of Union forces. He knew Ewell had Northern troops sitting in front of him, but he didn’t know enough specifics to make a well-informed decision on the matter.[22] What can be criticized is the Confederate’s assault itself; specifically the engagement of its divisions in peace meal, rather than simultaneously. Had Culp’s Hill been hit at the same time as Sickles’ 3rd Corps, or perhaps even before, arriving Union reinforcements may have been sent to other parts of the line, which could ultimately have led to a collapse of the Union left flank.

The Third Day of Battle On the morning of July 3rd, Lee’s army was in a less than ideal situation. Having failed to break Union lines the previous day, his adversary still held the vital high ground, but this time without the salient created by Sickles’ corps the day before. Not only that, but by now the rest of the Union Army had arrived and had reinforced Union positions to the south around Little Round Top and Big Round Top. Lee originally hoped to resume his attack on the left, but the events on Culp’s Hill that morning soon changed his mind. At around dawn, Ewell renewed his assault, but, after six hours of intense fighting, the Confederates were repulsed and driven off Culp’s Hill entirely.[23] Lee, who had been planning to use Culp’s Hill as a diversion to resume his attack on the Union left, was now forced to change strategy. Instead of hitting the flanks as he had done the previous day, he would try for the Union center. General Longstreet’s final division, commanded by General George Pickett, had arrived during the night; as it was the only Confederate division still fresh, Lee planned to take full advantage of it. Pickett’s division, along with Pettigrew’s, Trimble’s and two brigades of Anderson’s, would assault Union positions on Cemetery Ridge by advancing from Seminary Ridge across just over a mile of open ground. While a charge of this scale, and on open terrain, was bound to sustain heavy casualties, General Lee believed that Union forces in the center were weak. Lee ordered General Longstreet to plan the attack, a task that he took on grudgingly.[24]

The battle opened with a massive artillery barrage by Confederate guns (around 150) on Cemetery Ridge, which lasted from 1pm to 2pm. Union guns responded in turn, striking rebel artillery, as well as Confederate infantry concealed in the woods when shots went long. At around 1400, General Longstreet received the following message from his artillery commander, Colonel Alexander:

“If you are coming at all, come at once, or I cannot give you proper support, but the enemy’s fire has not slackened at all. At least eighteen guns are still firing from the cemetery itself. -Alexander”[25]

Pickett’s Charge (Courtesy of Roadboy’s Travels)

Filled with a sense of foreboding Longstreet gave a nod, as he was too distraught to speak, ordering the infantry forward.[26] The men, some 12,500 of them, quickly formed up and began the assault, heading for a large grove of trees on Cemetery Ridge. Unfortunately for the Confederates, the artillery bombardment had been ineffective. Not only was it nearly impossible for Confederate gunners to tell if they were hitting their targets due to the massive amount of smoke caused by the bombardment, but their shells were of poor quality, causing many to detonate to late, or not at all. It was not long before Union artillery began to take its toll, cutting large gaps in Confederate formations. As they advanced, they came into range of Union muskets and their ranks were further decimated. Most of the Confederate officers leading the assault were either killed or wounded. In the instance of a Colonel Whittle, who had lost his left arm and been shot through the right leg in previous engagements, was hit in both of his remaining limbs.[27] General Armistead’s brigade was able to successfully make it over the low stone wall that Union troops were positioned behind, but they were soon thrown back and Armistead was mortally wounded. The Confederates began to retreat, pulling back across the field while still taking heavy fire; several infantry formations were cut off by Union troops and shot to pieces. In total, the casualties Confederate casualties at Pickett’s Charge exceeded 50%. Lee’s final assault had failed, and the Confederate Army would never again be strong enough to go on the offensive.[28]

There were two other engagements that day, both involving cavalry. To the east of Gettysburg at 11am, Confederate cavalry under General JEB Stuart engaged Union cavalry under General David Gregg and the infamous General Armstrong Custer at the Rummel Farm, which resulted in a Union victory.[29] To the south around Warfield Ridge at 3pm, Union General Kilpatrick attempted to charge Confederate lines.[July 3rd: Kilpatrick’s Failed Charge] The ground he chose was very rocky and contained several fences; his men were subsequently cut to pieces.[30]

Courtesy of History Channel

Conclusion Union victory at Gettysburg, in combination with the fall of Vicksburg the following day, is considered the turning point of the American Civil War. The sheer number of casualties suffered by the Confederacy were simply irreplaceable, and Lee was never again able to take the offensive against the Union. Even if Lee had won (say the left flank collapsed on July 2nd or Pickett’s Charge broke the Union center), it is likely that Lee’s invasion of the north would still have ended, as his army was at ~62% strength after the battle and in enemy territory with no way to easily replenish its numbers.[31] However, defeat at Gettysburg could have cost the Confederacy the entire war. Had General Meade acted decisively, it is very likely that the Union Army could have caught the retreating Confederates before they crossed the Potomac River and obliterated them. Unfortunately, Meade was too cautious in his pursuit and missed the opportunity. Lincoln was furious and Meade offered to resign after realizing his mistake, but, as Meade had only recently taken command, Lincoln refused to accept his resignation and Meade remained commander of the Union Army of the Potomac for the remainder of the war.

The battle of Gettysburg is the 4th deadliest engagement in American military history, with roughly 51,000 total casualties (23,055 Union and ~28,000 Confederate) after 3 days of fighting in an area just over 9 square miles. Although only 7,863 Americans died compared to the 26,277 of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in 1918, the 19,276 of the Battle of the Bulge in 1944-45, and the 12,513 of Okinawa in 1945, Gettysburg lasted only three days while these other engagements lasted several months each.[32] Not to mention, if adjusted for population, the battle of Gettysburg would have taken 25,809 lives had occurred in the same year as the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which brings home just how devastating this three day engagement was, especially for the Confederacy, as they had seriously limited manpower compared to the Union.[33] To this day, Gettysburg remains arguably the most famous battle of the American Civil War, and hopefully we will not soon forget it, nor the sacrifices that were made on those Pennsylvania fields.

[1] Harry W. Pfanz Gettysburg–the First Day, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001) 51-68.

[2] Pfanz, 68.

[3] Pfanz, 69-79.

[4] Pfanz, 109.

[5] Pfanz, 115-130.

[6] Pfanz, 227-238.

[7] Stephen W. Sears, Gettysburg (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003) 224.

[8] Pfanz, 269-293.

[9] David G. Martin, Gettysburg, July 1,(Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo, 2003) 284.

[10] Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg–the Second Day, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001) 124.

[11] National Park Service. GETT_S2.pdf (n.d.): n. pag. National Park Service. National Park Service. Web. 28 Nov. 2016.

[12] Pfanz, 176.

[13] J. H. Hobart Ward, “Brig. Gen. J.H. Hobart Ward’s Official Report For The Battle Of Gettysburg.” Civil War Home. N.p., 4 Aug. 1863. Web. 28 Nov. 2016.

[14] Pfanz, 208.

[15] Pfanz, 232.

[16] Pfanz, 3.

[17] Pfanz, 334.

[18] Pfanz, 390-400.

[19] Pfanz, 410-414.

[20] Pfanz, 350-424.

[21] Gettysburg Battlefield Commission, comp. Pennsylvania at Gettysburg: Ceremonies at the Dedication of the Monuments Erected by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to Mark the Positions of the Pennsylvania Commands Engaged in the Battle. Vol. 1. Harrisburg, PA: E. K. Meyers, 1893. Accessed November 28, 2016, 204, 424. [Google Books]

[22] Pfanz, 104-113.

[23] Gettysburg Battlefield Commission, 603. [Google Books]

[24] James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America, (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1992), Accessed November 29, 2016, 388. [Google Books]

[25] Longstreet, 392. [Google Books]

[26] Longstreet, 392. [Google Books]

[27] Longstreet, 394. [Google Books]

[28] Longstreet, 394. [Google Books]

[29] “The Rummel Farm on the Gettysburg Battlefield.” The Battle of Gettysburg. Stone Sentinels, n.d. Web. 29 Nov. 2016.

[30] Longstreet, 395. [Google Books]

[31] U.S. War Department, ed. “The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.” Cornell Library. Accessed December 2, 2016.

[32] “10 Deadliest Battles in American History.” History Lists. WordPress, 18 Mar. 2008. Web. 26 Nov. 2016.

[33]”US Census Bureau Publications – Census of Population and Housing.” US Census Bureau. US Census Bureau Administration and Customer Services Division, n.d. Web. 26 Nov. 2016; “Historical National Population Estimates: July 1, 1900 to July 1, 1999.” Census.gov. U. S. Census Bureau, 11 Apr. 2000. Web. 26 Nov. 2016.