Background

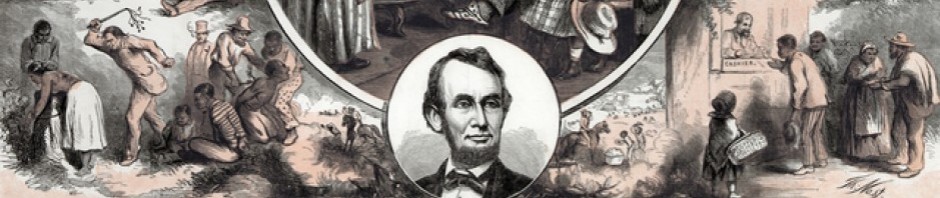

Gordon Wood titles the introductory chapter of his book Revolutionary Characters (2006) as, “The Founders and the Enlightenment,” because he believes that the Age of Enlightenment helped define the worldview of the American republic’s “founding” generation. Wood begins his analysis, however, by sketching out a brief history of how these founders have been portrayed in revisionist scholarship over the years. According to Wood, the most important revisionist work was by historian Charles Beard, whose Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913) was “the most influential history book ever written in America (p. 6). Wood also surveys recent criticism of the Founders from scholars now often more concerned about race than economic class. These morally-charged criticisms tend to focus on compromises the Founders made over slavery in 1787 and beyond.

Gordon Wood titles the introductory chapter of his book Revolutionary Characters (2006) as, “The Founders and the Enlightenment,” because he believes that the Age of Enlightenment helped define the worldview of the American republic’s “founding” generation. Wood begins his analysis, however, by sketching out a brief history of how these founders have been portrayed in revisionist scholarship over the years. According to Wood, the most important revisionist work was by historian Charles Beard, whose Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913) was “the most influential history book ever written in America (p. 6). Wood also surveys recent criticism of the Founders from scholars now often more concerned about race than economic class. These morally-charged criticisms tend to focus on compromises the Founders made over slavery in 1787 and beyond.  Revolutionary Characters appeared before the release of the very revisionist-minded 1619 Project from the New York Times, but it anticipated the debate which erupted after journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones argued in 2019 that, “Our founding ideals of liberty and equality were false when they were written,” and that, “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery” (Hannah-Jones, p. 14, 18). In fact, Wood has been prominent in the last couple of years among a group of notable historians who have been criticizing Hannah-Jones for making this claim.

Revolutionary Characters appeared before the release of the very revisionist-minded 1619 Project from the New York Times, but it anticipated the debate which erupted after journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones argued in 2019 that, “Our founding ideals of liberty and equality were false when they were written,” and that, “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery” (Hannah-Jones, p. 14, 18). In fact, Wood has been prominent in the last couple of years among a group of notable historians who have been criticizing Hannah-Jones for making this claim.

Wood’s argument in Revolutionary Characters is not that the Founders were above reproach, but rather that everyone needs to appreciate them in their context, which he identifies first and foremost as being from the Enlightenment era. The Yawp editors also highlight the influence of the Enlightenment on the Founders (especially philosophers such as John Locke), but Wood presents some distinct ideas about how the culture of period affected the leadership of the Revolution. He identifies two key categories:

- Civilization and gentlemanly manners

- Disinterestedness and character

Of course, George Washington aspired to be the embodiment of these sets of virtues. According to Ralph Waldo Emerson, “every hero becomes a bore at last” (See his essay “Uses of Great Men,” 1850). Gordon Wood employs this famous line from Emerson in his chapter on George Washington’s greatness as way to help us understand how Americans have come to take the once-revered “Father of Our Country” for granted. He argues that Washington’s greatness remains misunderstood and under-appreciated, because it has been wrenched out of its Enlightenment context.

Of course, George Washington aspired to be the embodiment of these sets of virtues. According to Ralph Waldo Emerson, “every hero becomes a bore at last” (See his essay “Uses of Great Men,” 1850). Gordon Wood employs this famous line from Emerson in his chapter on George Washington’s greatness as way to help us understand how Americans have come to take the once-revered “Father of Our Country” for granted. He argues that Washington’s greatness remains misunderstood and under-appreciated, because it has been wrenched out of its Enlightenment context.

To begin, Wood claims that “Washington’s greatness, lay in his character” (p. 34). Students in History 117 should be able to explain what the author means by this claim. What were some of the key elements of Washington’s “character” that Wood examines in detail?

One revealing test of Washington’s character by Wood’s estimation was how he treated his slaves. The historian provocatively calls the owner of Mount Vernon “a good master” (p. 39), and details the story of Washington’s famous ambivalence about slavery and ultimately how he promised to manumit or free them upon his wife’s death. How do you think Nikole Hannah-Jones would react to this interpretation?

Another test of Washington’s character came with his seeming ambivalence over holding power. Wood offers a series of fascinating insights about how the great founder approached his various “retirements” from public life and how he navigated sometimes-complicated episodes challenging his legendary disinterestedness. Summarizing these episodes, Wood quotes from scholar Garry Wills who once observed that Washington, “gained power from his readiness to give it up” (p. 47). Students in History 117 should be able to explain the meaning behind this shrewd line.

Case Studies: Washington in Action

1758 –The Young Politician: Standing for Office vs. Running for Office

1778 –Washington as Wartime Commander and “Governing Principles”

1787 –Washington and Founding Mother, Elizabeth Powel

1794 —Washington in Carlisle: Leading By Example

1796 — President Washington Offering Farewell Advice

Below: “One Last Time” from musical “Hamilton,” performed at the White House in 2016, a musical rendition of Washington’s Farewell Address (1796)

The unity of government … is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very liberty which you so highly prize. But as it is easy to foresee that, from different causes and from different quarters, much pains will be taken, many artifices employed to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth; as this is the point in your political fortress against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly and insidiously) directed, it is of infinite moment that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national union to your collective and individual happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual, and immovable attachment to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as of the palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned; and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.