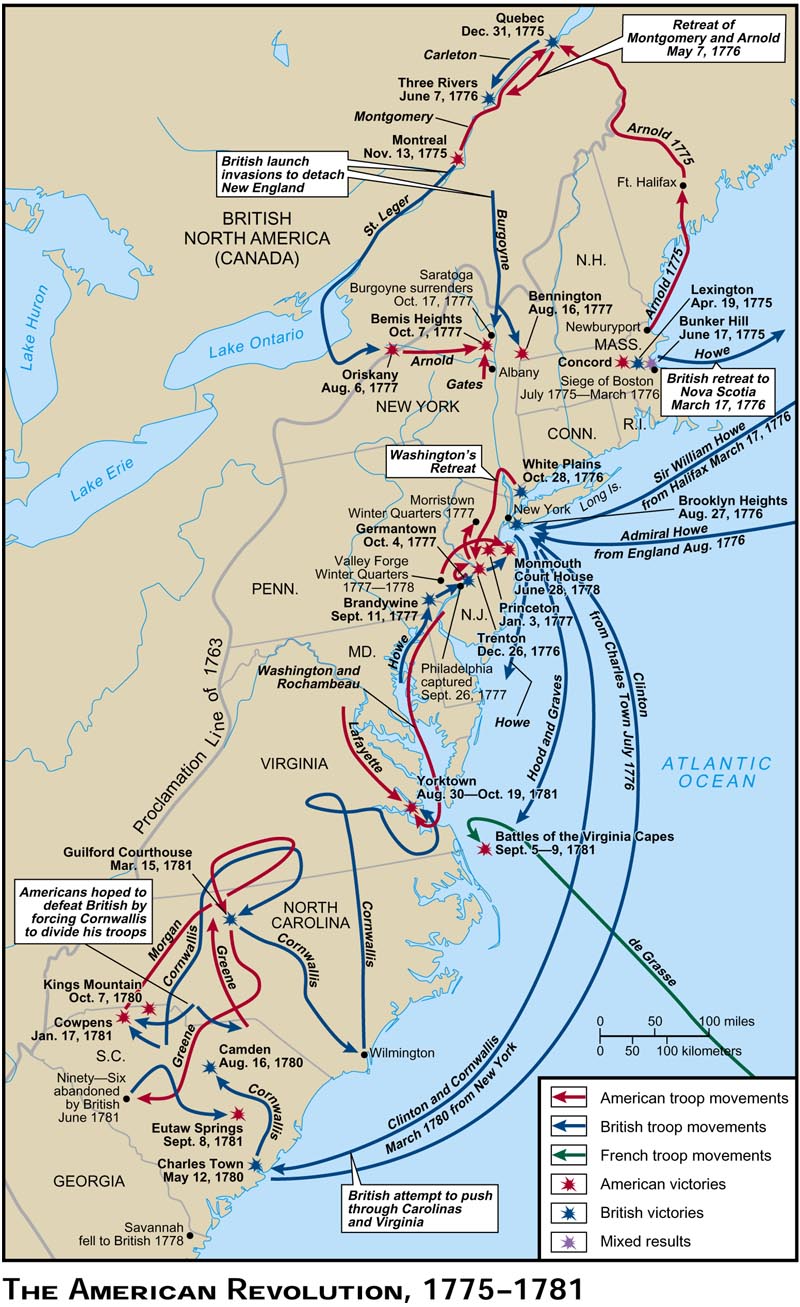

Who declared American Independence? The answer is not quite as simple as it appears. Gordon Wood relates how some observers remarked later that Sam Adams of Boston had at least decided on independence as early as 1768, following enactment of the Townshend Duties. One thing is clear in Wood’s account of the movement from resistance to rebellion –there was a real sense of American Independence readily apparent by 1774. That was the year of the Coercive Acts and what Wood characterizes as “open rebellion in America.” Students in History 117 should be able to identify a variety of ways that the authority of the British imperial system quite literally fell apart in the American colonies during the period from 1774 to 1775. Yet still, there was no “declared” independence until the summer of 1776. Nonetheless, it is not enough to simply reward the credit for American Independence to the decision-making of the Second Continental Congress and the prose of Thomas Jefferson. According to Wood, it was Tom Paine, more than any other figure, who most fully expressed “the accumulated American rage against George III.” Students might benefit from studying this rage in Paine’s sensational pamphlet, Common Sense (1776) or by analyzing its influence on the “long train of abuses” which dominate the second half of the Declaration of Independence. Yet regardless of how exactly independence got declared, or how to explain the ideology which lay behind it, one Founder who was noticeably reluctant about embracing this revolutionary step was John Dickinson, the famous pamphleteer. Dickinson warned his colleagues on July 1, 1776 that with their declaration that they would be attempting to “brave the storm in a skiff made of paper.” Dickinson soon came around to the cause, but his fears remained a recurring concern for many. Securing independence proved even far more challenging than declaring it.

Matthew Pinsker

House Divided studio (61 N. West)

Email: pinskerm@dickinson.edu

Twitter: @House_Divided

Office Hours: Wed 9am to 12pmAdministration

Thanksgiving myths? Say it ain’t so! Yet in History 117, students are reading a handful of short, insightful essays by

Thanksgiving myths? Say it ain’t so! Yet in History 117, students are reading a handful of short, insightful essays by