By Caly McCarthy

2020 Preface Written By Author

Recently, I was on Facebook and saw a post from the Dickinson History Department regarding the Pinsker Student Hall of Fame. I followed the link and was tickled to see my oral history from 2015 there. However, as I was re-reading it, to be honest, I was cringing at how I framed things.

When I wrote this narrative five years ago I thought that it was a fine piece of oral history, but I no longer hold this position. I failed to acknowledge even once that “riot” is a loaded term that frequently gets employed along racial lines. I should not have used the phrase “young blacks.” I should have contextualized my dad’s comment about “smoldering resentment” to emphasize the inequality that Black people face living amid racist systems. I should not have leaned on a superficial understanding of MLK’s commitment to nonviolence to decry the looting and arson that followed his assassination. I should have questioned the use of the National Guard and martial law in DC.

I thought I was being neutral. I thought that I was simply portraying my dad’s experience. Instead, I unwittingly dismissed the chronic reality of racism in our country by centering this moment in history on property damage and white fear. I offer this preface as an invitation to accountability. Because the way we frame stories about race, violence, fear, and property damage have very real implications for whether we amplify or delegitimize Black lives, cries, and calls for change.

Original 2015 Oral History

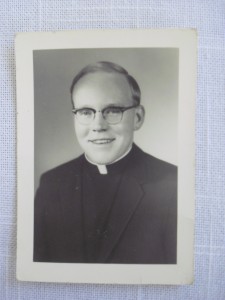

Photograph of Father Joe in 1969, one year after McCarthy was ordained a deacon.

On the day that James Earl Ray assassinated esteemed civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr., Joseph McCarthy was ordained a sub-deacon of the Catholic Church in Washington, D.C.[1] Historian H.W. Brands argues that word of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination “flashed across the continent and triggered the largest wave of riots to date.”[2] Though cities throughout the nation erupted into riots, civil unrest in Washington, D.C. was especially strong. McCarthy remembers climbing on the rooftop of Catholic University, surveying the city, and observing that “[w]hole blocks were on fire.”[3] McCarthy’s recollections of the riots in Washington, D.C. illustrate the fear and confusion of the time immediately following MLK’s assassination. His recollections of this single uprising offer a vivid account of the race riots that dominated America in the late 1960s.

In preparation for his ordination, McCarthy had attended Montford Prep, a boarding school in New York state. He later attended St. Mary’s College in Kentucky for his undergraduate degree, where he majored in philosophy and minored in classical languages. After graduation he continued study at Kenrick Seminary of St. Louis, Missouri, and Catholic University of Washington, D.C.. On April 4, 1968, McCarthy was just shy of 28 years old. He had lived in Washington, D.C. for three years, and the violence that erupted did not come as a total surprise. He recalls identifying a feeling of “smoldering resentment” among young blacks whom he encountered while walking and taking the bus day after day.[4] Although no one was explicitly hostile towards him, there was a palpable sense of tension, evident by glares and body language. He posits that, unlike previous generations, young blacks had exposure to television. This medium regularly showcased a white standard of living unattainable for blacks and broadcast news of urban violence based on racial tensions. It made injustices more visible, and McCarthy suggests, fed frustration among the black community.[5]

The race riots that plagued the 1960s were manifestations of frustration over slow progress. Brands comments, “The promise of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the rest of Johnson’s Great Society seemed distant and often irrelevant to the trials of everyday life on the streets.”[6] Fueled by immense frustration regarding high unemployment, low-quality schools, and inadequate housing, small disputes with police escalated into urban riots. Such was the case in Watts, a neighborhood of Los Angeles, California in 1965, and in Newark, New Jersey and Detroit, Michigan in 1967. Hallmarks of the riots included looting businesses (especially, though not exclusively white-owned), setting fire to the city, and strong response by the National Guard. The riots always yielded loss of order, property, and life.[7]

The riots that followed MLK’s assassination were notable in both frequency and magnitude. Scholar Peter B. Levy asserts that “during Holy Week 1968, the United States experienced its greatest wave of social unrest since the Civil War.”[8] Nearly 130 cities in over 36 states experienced violence in the wake of MLK’s death.[9] Washington, D.C. witnessed twelve days of rioting. By the end, 13,600 troops, “more than were used in any other riot in the nation’s history, occupied the city and regained control.”[10] Before the rioting ended, 13 people died, 7,600 were arrested, and $24 million’s worth of property damage was incurred. Washington D.C. boasted 1/3 of the nation’s insurance claims for destruction that followed MLK’s death.[11]

McCarthy recalls that amid all of this unrest, his family managed to get into the city and attend his ordination. He says that they left immediately after, and that “the streets were absolutely bare. You were not allowed out on the streets. No buses. It was eerie, and sad, and frightening.”[12] In noting that no one was allowed on the streets, McCarthy references the official state of emergency that President Johnson and Mayor Walter Washington declared over the city.[13] City officials had prepared emergency measures in advance of MLK’s Poor People’s March, set for April 22, 1968. They had cause to use them earlier than planned, in light of the rioting that followed MLK’s assassination. The city trained police officers in mob psychology and urged them to have few visible officers and to avoid unnecessary use of sirens, so as to reduce targets for violence. Additionally, the training instructed officers to make arrests quietly. With regards to emergency measures, a curfew was enacted and the sale of gasoline, firearms, and alcohol was prohibited.[14] City officials enacted these policies in hopes of eliminating magnifiers of aggression. Even so, rioters disrupted the city a great deal. McCarthy remembers, “One of my friends and his wife got stopped at a red light, and a whole group of people went out and rocked their car, and this woman was like 8…8 ½ months pregnant, and it was pretty upsetting.”[15] Emergency measures may have helped minimize further physical damage to the city, but its inhabitants were rattled nonetheless.

Arson was a primary source of damage to the city, in addition to looting and rioting. Schaffer notes that when the rioting was most intense, D.C. fire stations received twenty-five to thirty calls per hour, reporting arson and requesting assistance. Upon arriving at the scene, however, fire fighters found hostile crowds who denied them access to the buildings, rendering them incapable of eliminating the fire. Although white-owned businesses were especially targeted, black-owned businesses were not immune from damage. As a strategy to minimize damage, some black-owned businesses posted signs marking themselves as “soul brothers.” While the signs may have prevented further destruction, fire damage still created two-thousand homeless and five-thousand unemployed.[16]

Martin Luther King Jr. was a national icon for non-violence. When he was assassinated, Americans around the nation mourned his death. Yet some responded to this tragic loss in a most violent manner. In doing so, rioters caused immense damage through the acts of looting and arson. They spread a spirit of fear and confusion, as is apparent from the recollections of Joe McCarthy, ordained a deacon in Washington, D.C. amid the MLK riots of April, 1968.[17]

[1] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (audio recording), Hackettstown, NJ, March 10, 2015.

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 159-160.

[3] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (audio recording), Hackettstown, NJ, March 10, 2015.

[4] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (phone conversation), April 27, 2015.

[5] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (phone conversation), April 27, 2015.

[6] Brands, American Dreams, 148.

[7] Brands, American Dreams, 148-150.

[8] Peter B. Levy, “The Dream Deferred: The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Holy Week Uprisings of 1968.” Maryland Historical Magazine 108, no. 1 (2013): 57-78.

[9] Eric Juhnke, “A City Awakened: The Kansas City Race Riot of 1968.” Gateway Heritage: The Magazine of the Missouri Historical Society 20, no. 3 (1999): 32-43 [America: History and Life].

[10] Schaffer, “The 1968 Washington Riots”: 15 [JSTOR].

[11] Schaffer, “The 1968 Washington Riots”: 5, 12 [JSTOR].

[12] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (audio recording), Hackettstown, NJ, March 10, 2015.

[13] Schaffer, “The 1968 Washington Riots”: 12 [JSTOR].

[14] Schaffer, “The 1968 Washington Riots”: 9-10, 16 [JSTOR].

[15] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (audio recording), Hackettstown, NJ, March 10, 2015.

[16] Schaffer, “The 1968 Washington Riots”: 17, 19 [JSTOR].

[17] Music clip: http://www.freesound.org/people/nicStage/sounds/1906/

Leave a Reply