By Molly LaBelle

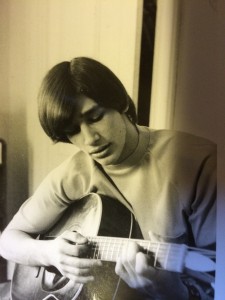

In 1973, Don LaBelle was newly independent. Living in a small apartment on his own in Rochester, New Hampshire, he commuted each day to school and work. Don grew up alongside many brothers and sisters in poor family and worked for most of his childhood. As a teenager, he played football, played the guitar, and was deeply invested in his hair. He was a typical young boy of the era, trying to get by while still enjoying his youth and freedom. However, his youth was quickly taken away from him when the first oil crisis hit: “all of the sudden I had to spend a lot more money on gas. You had to make sure you had gas” he remembers [1]. Like Americans across the country in 1973, Don was forced to make sacrifices like he never had to before. For the first time after the birth of American consumer culture, people were not able to get something they depended on for their daily lives. H.W. Brands puts it best when he notes that “gas shortages were un-American, something people in other countries endured but not citizens of the United States. And Americans were used to being in a hurry and driving fast”[2]. Brands’ interpretation of the crisis helps us to understand that American people now began to question their entitlements to material goods that they had always enjoyed, entitlements that were uniquely American.

The oil crisis and shortage began in October of 1973 when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries enacted an embargo on oil exports as a political weapon against Isreal. The use of oil as a weapon began as a result of Israeli occupation in Egypt and portions of the Sinai Desert and Gaza Strip. The occupation occurred after a violent and short war with Egypt that easily pitted the countries against one another. By stopping the flow of oil, the OPEC nations were directly punishing Israel for its actions, however, they were also indirectly punishing the United States for quietly taking Israel’s side in the conflict. As relations with Middle Eastern countries deteriorated, the U.S. was warned numerous times that if it did not stop its ally with the enemy, the OPEC nations would institute their embargo, essentially stopping the flow of 12% of the United States total oil supply.

While the embargo certainly had an effect on foreign oil affairs, things were already bad on the home front when it hit. Robert Lifset argues that the shortage of oil came long before the embargo, which happened to be a convenient “scapegoat” for the American government[3]. Before the embargo, the American fuel market had already been under strain that would cause a shortage. According to Lifset, when the U.S. was at peak oil production in 1971, President Nixon froze prices. At this time, gas prices were high and heating oil prices were relatively low. This led to the increased demand for heating oil thus increased focus on this by the production companies. The lack of focus on gas created a dramatic drop in supply that caused shortages four months before the OPEC embargo in June. This, then, was only worsened when the embargo was enacted in November of 1973. Both domestic and foreign oil were scarce and the United States bore the brunt of the shortage.

Changes in lifestyle began to show throughout America as soon as the shortage began. What little luxury and leisure people enjoyed slipped away quickly. Don remembers the loss of Sunday drives most clearly:

“This is gonna sound funny, but all the time when I was growing up, when I was young, they used to have something called a Sunday drive. That’s why you hear people called Sunday drivers. And it was a real big thing. People, on Sunday, would go on nice long drives, just kind of exploring in their cars. You know, go to places that they haven’t been before. Go up north… people from Massachusetts would come up. People would take drives to different parts of the state, visit some relative that was quite a way away. Always on a Sunday. Then you couldn’t do that, because you weren’t sure if you were going to have gas[4]”.

While this may not have been a major loss for some Americans, others like Don, felt that a certain charm of American life had suddenly faded away. The U.S. was a place where hardworking people like himself could enjoy things like Sunday drives and explorations. Now that Americans were confined to their homes in fear that they would run out of gas, they felt trapped.

In many ways, the oil crisis took Don’s teenage “innocence” and optimism away from him to soon. He loved his 1968 Ford Grand Torino GT Fastback that he had worked so hard to purchase. Now, as he struggled to finance his travels, it seemed like more of a burden than a luxury. Now, when he went to the gas station, there were feelings of fear rather than relaxation. Don recalls that before the crisis people never pumped their own gas. “The employees would pump it for you and you would get out and clean your windows and talk to people around you[5]”. During the shortage, people came to the gas station on edge and worried that fuel would run out before they got the chance to fill up: “people were more stubborn than anything” because they wanted their gas and their freedom, Don recollects.

Especially in New England, were people on edge. Here,the crisis posed unique threats and problems. Since the embargo was passed in November, it fell right before the eve of a typically harsh New England winter. And if gas was in low supply, naturally heating oil was as well. Don knew the importance of this heating oil in such a cold area: without it, your pipes would freeze and this would cause extreme damage to your home. You had to have heating oil, just like you had to have gas. Newspapers in the region warned that New England would be hit the hardest as the rising demand for heating oil would not be met in time for the winter. One New York Times article predicted that since New England’s oil needs were met primarily by independent companies, the shortage could have a deep and lasting impact on the area[6].

Some good things did come out of the crisis. The shortage of oil certainly helped people to realize that America’s energy independence was crucial to its security interests. Americans began to seek alternative forms of energy and improve the forms they were already using. Don became acutely aware of this after the crisis. A short article in the New York Times from 1973 details how one college professor began trying to use wind as a cleaner and more dependable form of energy in the United States[7]. In addition to efforts like these, car companies began to make smaller, more efficient cars. This change was a lot closer to home for most Americans. Even Don himself put an effort towards depending less on oil. After the crisis, he made sure to buy a smaller car that was more efficient on gas. He sacrificed looks and style for practicality.

In the midst of the oil crisis and the years following it, Americans developed into different kinds of consumers. Instead of taking and taking without any thought, they began to realize how unique America was with its prosperous capitalist society. Don explained that he had never experienced anything being rationed before, much like many Americans during that time period. American consumer culture continued to grow and expand up to the 1970s and allowed people to have whatever they wanted in almost no time. The gas shortage caused them to question the lifestyle they had now become accustomed to.

“You never had food that was rationed; there wasn’t anything that you couldn’t get enough of that you needed. Other countries have experienced this quite a bit. But in the United States, you never had that before. You know, you go to the grocery store and the shelves are all full all the time, or you go to buy clothes and the shelves are all full… or shoes, or any commodity. And it kind of really made you wonder, if it can happen with oil, what else can it happen with?[8]”

It was feelings like these that caused people all over the country to realize that they were not always in control. They would not always be able to get the things they needed or wanted whenever they needed or wanted them. The oil crisis of 1973 and the similar crisis that followed in 1979 helped to dampen Americans’ sense of entitlement and open people’s eyes to the role that foreign affairs could play in their daily lives.

[1] Phone interview with Donald LaBelle, April 20, 2016.

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 196.

[3] Lifset, Robert D, “A New Understanding of the American Energy Crisis of the 1970s”. Historical Social Research. (2014), 39.

[4] Phone interview with Donald LaBelle, April 20, 2016.

[5] Phone interview with Donald LaBelle, May 1, 2016.

[6] “Oil Outlook Dark For New England,” New York Times, September 29, 1973 [ProQuest]

[7] “Hot Air 1973,” New York Times, January 1, 1973 [ProQuest]

[8] Phone interview with Donald LaBelle, April 20, 2016.

Leave a Reply