In his book, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945, H.W. Brands offers insight into race relations up until the Civil Rights Act. Although detailed depictions of race relations trail off post-1964, Brands writes “Americans challenged poverty, inequality, and prejudice and mitigated these historic scourges substantially.”[1] His recognition of mitigation connotes that racial integration continued as American society addressed equality issues in daily life. The real-life accounts of people who came of age after 1964 reveal practical lessons and challenges of true desegregation, not based on legal precedent or legislative mandate but upon personal connections among people.

Brown v. Board II (1955) prohibited segregation in schools, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation in all other aspects of life, ending the longstanding “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Although history notes that the effects of Brown and the Civil Rights Act were not felt immediately, history often fails to articulate the everyday process of integration. Real integration happened beyond the headlines and court cases. Judicial rulings cannot educate ordinary citizens about how to enact change, especially when upending multigenerational norms. Such change takes time.

Andrew Kevin Blackwell, born in 1964, lived through the aftermath in the small town of Monticello in southern Mississippi’s Lawrence County. Blackwell recounts growing up in the newly integrated South. He began first grade in 1969, the same year Monticello’s school system was desegregated. He says, “My class was the first to actually go all the way through school in an integrated system.”[2] It was not until the following summer, in 1970, that all public schools in Mississippi were fully integrated.[3]

Blackwell describes being unaware of racial issues. He says, “I was six years old and more interested in baseball and frogs … than I was in race relations at that time.”[4] He said, “All of my neighbors for miles in any direction were white.”[5] Once he went to school, he met many black children, but “society there was [still] segregated.”[6] For example, school buses were one of the numerous aspects of life that remained segregated. Blackwell described how the buses lined up outside of school every day with a clear distinction between those ridden by the white student versus black students:

One day in the fifth grade, [I see] a different bus located where [my bus] is supposed to be…this bus was dilapidated, it was old…the seats were torn…And all of my black friends who were going to get on their bus were laughing at us basically saying, “you get to ride the n-word bus today.”[7]

Blackwell noted the delineations among white students as well: the town kids and the farm kids. The town kids’ “parents were on the school board,” and those students had the newest buses.[8] The farm kids, like Blackwell, rode the average buses; they were not shiny and new like the children in town, but they were not run down like the buses for the black students. While Brown v. Board of Education dictated school integration, communities leveraged the decision’s lack of implementation details to funnel resources away from black students.

In 1976, the bicentennial brought joyous celebrations and filled classrooms with discussions of the nation’s founding. A school field trip took his sixth-grade class to the local theater to watch the movie 1776. He recalls, “I was thinking on the way over there, you know, I’ve never seen any black kids at the movie theater. That’s a white kid thing.”[9] Upon arrival, Blackwell entered through an unfamiliar side door. It was dark and led to a steep, narrow stairwell that he did not know existed. At the top of the stairs was a balcony. When he sat down, his chair

broke. His friend in the next chair, Bessie, “looks at it and says, well get used to it. That’s what we deal with all the time.”[10] Bessie was a black girl. The reason Blackwell had never seen the black kids at the theater was that they sat in the rundown balcony, despite no rule forcing them to do so. For the black students, “it was just understood that’s the way it had always been.”[11] Black and white students attending a movie together to celebrate the bicentennial marked significant progress, but racial separation remained omnipresent two centuries after the country’s founders grappled with the issue of slavery. As 1776 illustrates and Brands writes, “Americans have been dreaming since our national birth,” but full racial reconciliation remained unfulfilled.[12]

Blackwell relayed a subsequent story from high school. A white friend who lived in town, Shellie, came to him for help. Her mother and other mothers were hosting a pool party, so Shellie was talking to friends, both white and black, about attending. When other mothers learned that black friends were being invited, “as politely as southern ladies can be polite, not necessarily nice, [the mothers] basically told Shellie, go back to school and tell ’em all they can’t come.”[13] Shellie wondered what to do. Blackwell proceeded to tell their black and white friends about the situation, effectively beginning a boycott of the party. Embarrassed by the situation, the hosting mothers retracted their previous statements, and Blackwell told everyone to go. He said, “We all got along and here intrusive mothers are driving wedges between us based upon rules that we didn’t have anything to do with creating, nor certainly any interest in propagating.”[14] This event illustrates the progress of breaking generational attitudes. Shellie had no hesitation about inviting her black friends, but other parents were making unfair rules. So, Shellie and other students responded. The host parents’ swift retraction demonstrates that the new generation was intolerant of rules against their black peers and supports Brands’ belief that “the moral foundation of America’s dreams had always been the right to dream, and Americans weren’t about to surrender that.”[15]

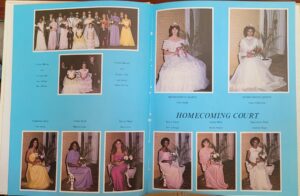

Buses and the local movie theater were two examples of segregation’s remnants that followed Blackwell as he moved into high school in the fall of 1979. Perhaps coincidentally, some policies put in place in order to combat segregation created further divides. For example, in order to create the opportunity for black students to be homecoming king and queen, even with a student body that was 55% white and 45%black, the school board implemented a policy to have both a black homecoming couple and a white homecoming couple. This well-intentioned policy further projected a divide among students that Blackwell said had largely diminished by the time he began high school. Students began to reject “these old archaic rules and stupidity that was created many, many years ahead.”[16] The homecoming dance itself was another issue. The attitude of the school’s administration was, “Now you got white kids and black kids dancing together…No way!”[17] The solution was not to have a dance between 1970 and 1980 The students eventually took a stand against the administration, leading to the first integrated homecoming dance in 1980.

In 1969, the Supreme Court ordered the Fifth Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals to enforce the desegregation of schools in Mississippi, which led to integration in 1970. However, de facto segregation in Mississippi remained prevalent after this order, and private schools emerged as an alternative to public education. Lawrence County Academy opened in 1970 in Monticello, Mississippi, Blackwell’s hometown. The all-white school began as a so-called “segregation academy,” even selecting The Rebels, a nod to the Confederacy, as its mascot.[18]

Further, in 1984, a group of black families filed formal complaints about continued segregation in Lawrence County. In United States v. Lawrence County School District, the Circuit Court ruled that the county’s tri-district school system reinforced racial segregation in the small, mostly white Topeka and New Hebron districts.[19] As buses remained segregated in integrated districts, in 1984, the U.S. demanded that the 1969 order be enforced, and the judge presiding over the case found that Lawrence County had not implemented the 1969 ruling. In response, the Lawrence County school board voted to combine the tri-district into a single one. Blackwell noted that the community largely supported this approach because it created a larger district that could better utilize resources.[20] To eliminate the vestiges of past rivalries, the newly-formed Lawrence County School District created new mascots and school colors.

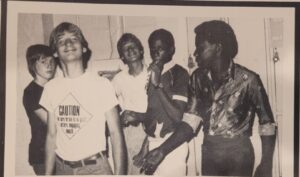

Blackwell (middle) with brother and friends, Monticello High School Yearbook, 1980, from Andrew K. Blackwell.

The path to true integration was a long one. Beyond the court cases and headlines, “the dreaming persisted,” and residents of small towns like Monticello, Mississippi, desegregated schools and communities.[21] The integration process extended far beyond the 1960s. Residents did not have a clear roadmap, and as children, people like Mr. Blackwell formed friendships across racial lines and challenged long-standing social norms. True integration occurred through daily activities, sports, and hallway conversations, far away from courthouses and news cameras.

[1] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), x.

[2] Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[3] Charles C. Bolton, “The Last Stand of Massive Resistance: Mississippi Public School Integration, 1970” (Mississippi Historical Society, February 2009), https://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/the-last-stand-of-massive-resistance-1970.

[4] Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[5] Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[6] Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[7] Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[8] Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[9] Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[10] Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[11]Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[12] Brands, ix.

[13]Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[14]Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[15] Brands, x.

[16] Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[17] Video Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

[18] Ashton Pittman, “Hyde-Smith Attended All-White ‘SEG Academy’ to Avoid Integration” (Jackson Free Press, Inc., November 23, 2018), https://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2018/nov/23/hyde-smith-attended-all-white-seg-academy-avoid-in/.

[19]Alvin B. Rubin, “United States v. Lawrence County School Dist” (Casetext Inc., September 15, 1986), https://casetext.com/case/united-states-v-lawrence-county-school-dist/.

[20] Phone Interview with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, May 6, 2023.

[21] Brands, x.

Appendix

“The promise of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the rest of Johnson’s Great Society seemed distant and often irrelevant to the trials of everyday life on the streets.” (H.W. Brands, American Dreams, p. 148)

Interview subject

Andrew Kevin Blackwell, age 58, grew up in a small town in newly integrated South Mississippi in the 1960s and 70s.

Interviews

– Video recording with Andrew Kevin Blackwell, April 23, 2023.

Q. So Brands doesn’t really discuss race relations post-Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. He does acknowledge that these acts didn’t eradicate racism from America, the South in particular, but doesn’t continue the race discussion afterward. What was your experience like growing up in the newly integrated South?

A. So, just to put myself in the proper timeframe here, I’m 58 and a half years old, and so schools were integrated in Mississippi in about 1969, just as I was entering the first grade. And back then in Mississippi, we didn’t have kindergarten, so all students started school in the first grade. So I was the first in my county, a rural county in Mississippi called Lawrence County. I was the first class, my class was the first class to actually go all the way through school in an integrated school system. I never went to school with whites. Only there were blacks in my school system. That said, uh, there was a lot to, um, deal with, not so much me because I never knew any better. And I was six years old and more interested in baseball and frogs and whatever else than I was in race relations at that time. But definitely, society there was segregated. And so the first time, other than a black family, a man and a woman older who lived on the property where I lived, close by and on a family property, rented a house there and served as our, my part-time babysitter, I never met or dealt with any black people whatsoever until I went to first grade. Uh, I have an older brother who’s two years older and he went to first two years of school in an integrated school system, only white kids. Sometime during his second grade, they started integrating the schools. So that was kind of my perspective. It was limited. My parents would give you a very different, um, perception of what was going on there, I would assume because they actually had an understanding of the politics, the Civil Rights movement, the Civil Rights Act, Martin Luther King. I wouldn’t have heard of him in the first grade. I wouldn’t have known who he was. So I think it does, um, I, I’ve always consider it a unique perspective to have gone to the first grade or, you know, from first grade through 12th, uh, integrated with black students. I had the same, you know, there wasn’t a lot of in and outgoing students in rural Mississippi. So pretty much most of the kids that I started first grade with, I graduated with in high school after 12 years. So a couple of, um, interesting points. And incidentally, I actually write short stories about these experiences. I called a grouping of the short stories remnants, that’s the name of, uh, list of short stories. Most of these stories I just tell as I will do today, but I have a few of ’em that I’ve started writing down. And one day when I finally retire, I’ll, I’ll finish ’em. But they’re just stories of experiences of a young kid anywhere from first grade to about, well, really senior in high school, just different things that happened to me or that I was involved in or aware of that sort of gave a unique perspective on what it was like to integrate with a bunch of black kids that you didn’t have anything to do with outta school. These are actual true experiences, true stories of things that happened.

Q. So I think, of course, the Civil Rights Act was really monumental legislation, but it sounds very much like society was still very much segregated, despite the fact that legally, that was not the case.

A. That’s correct. I’ll give you a real story. This one I called number 29. That’s the name of the story. When I started school in the first grade, my brother had been going to school for two years. He was going into the third grade and every day the school bus, we lived in a rural community about eight miles from town. And the town is where the school was. So we had to ride the school bus to town every day. All of my neighbors for miles in any direction were all white. And the black kids, the black families lived in other parts of the county, some in the town part in the center of the county, some of ’em in more rural areas. But we didn’t encounter them on any given day. I’d never had black friends that I went fishing with or anything like that when I was really young. So my brother always, I watched him get on the school bus every day and go to school and the school bus was number 29. All the school buses were numbered. And I couldn’t wait to start school and get on old number 29 and go to school with my brother and all of my friends because all of my friends were on that same bus. We lived in the same area, same general area, big farms and all. All my friends were on number 29. So I went on number 29 all the way through first and fifth grade. Uh, and in the fifth grade I went to the middle school. Now it’s interesting how the schools went before integration in my county, there were three schools for the white kids. They had two schools. One, the Monticello Elementary School, which went first through sixth grade if I recall correctly. And then the high school, which went eight or seventh through 12th grade. That’s what the white kids did. And that was called Monticello Elementary and Monticello High. The black kids went to another school, it was called McCullough High School at the time, or McCullough School I think. It included all 12 grades and only black kids and black teachers went there. When integration came, the solution to actual buildings was to keep the elementary school, but take the fifth and sixth grade out of it. So all the kids went to Monticello Elementary School, first through fourth, middle schoolers, fifth through ninth grade went to McCullough, which they renamed McCullough junior high. And then for high school, 10th through 12th, we all went to the integrated high school, which was the white kids high school originally. So in the fifth grade I was at McCullough Junior High, which had been the black school. Interestingly McCullough was the name of a guy. He was the superintendent of education some years before. And they named that black school after him. And he was a white guy, superintendent of education. He was a white guy. So in the fifth grade, I leave one day after school, right bell rains. We all go to the school buses and the school buses are lined up down this street. Two in two different columns, basically Two buses, two buses, two buses on the on back. And I never paid much attention. My bus was always at a particular location, old number 29. And I went and jumped on it and all my friends were there. And the bus would go from the elementary school to the junior high pick up students, then to the high school, pick up more students, and then start going out into my community and dropping ’em off. So I get there one day in the fifth grade after school and there’s a different bus located where old number 29 is supposed to be. And I was confused. So I looked and in fact my bus driver was on there and all my friends were on there. But this bus was dilapidated, it was old, it had, the seats were torn, it had duct tape all over the seats, keeping them together. And I thought, what the heck? Why are we riding in this? And all of my black friends who were going to get on their bus were laughing at us basically saying, you get to ride the n-word bus today. And that was one of the buses that they rode every day. And I had never paid attention. But if you actually look at the buses, the way they were lined up, there were three statuses of buses. The first four were brand-new shiny buses. And they took all of the kids from town whose parents were teachers or doctors or you know. And all of the black buses that were, I don’t know, maybe three or four, maybe five were at the back of the line. And those buses, none of them were new. The, the one they had given us our bus that day had broken down, had a problem, whatever. And the school system kept one or two extra buses in case they had a problem with the bus. And because old 29 was broken down, they gave us this old broken down bus that wasn’t even good enough for the black kids. Right. It wasn’t, they didn’t even rate that on a day to day. Uh, you know, they, they, they had a little bit better buses than that, but not much. So it taught me something that, while there was definitely a black-white divide in rural Mississippi at that time, there were other divides as well. There were the town kids whose parents were on the school board. There were the farmers’ kids who were in the middle tier and were sent with average buses. And then the black kids. And I always thought about those drivers. All the black buses had black drivers, all the white buses had white drivers. And I was never aware of a black kid being on a white bus or vice versa. So the school, the bus system was still very segregated, very segregated many years after the school systems actually integrated. And I don’t think most people know that. But it also taught me, you know, there’s, there’s a little bit of a divide here, even, but among the white kids, and maybe there were some I didn’t understand among the black kids, I’m not sure. But, um, anyway, that’s my story of old 29.

Q. Would you say that the, um, black families and as there still a noticeable difference in sort of the jobs that black people tended to have or like those kinds of things?

A. Yes, there were differences. I’m not sure that they would be as stark as some of the ones with the white kids. Just cause, you know, some of the white kids’ parents were better educated and made more money. In some cases, some cases not. I mean, some of those farmers in rural Mississippi were loaded, right? Some of them made a lot of money, but their kids were different. They didn’t live in town. They didn’t swim in swimming pools. We swim in rivers and lakes. We went hunting and fishing. We did play baseball, but we didn’t play a lot of other sports. The town kids had a diving team. We never dreamed of having a diving team among the rural kids, you know. So, um, I can tell you another story if you want.

Q: Go for it.

A: Okay. So in the sixth grade was 1976. And what was 1976?

Q: The bicentennial.

A: The bicentennial. Now of course you weren’t born yet, but that was a big deal, the 200 anniversary of our founding of our nation. And they printed, they had all kinds of, you know, all kinds of activities in, in America to celebrate the bicentennial all year long, but especially around July 4th. But really all year long, lots of things educational-wise. They printed new coins, whatever, all celebrating the bicentennial. So one day at school, I’m in the sixth grade, and they load us all up in these buses, all of the fifth and sixth graders as I recall. And they took us across town to the local movie theater. Now, the bigger town, which you’ve been to Brookhaven even back then, had a more modern movie theater. Not quite as slick as they have ’em today, but you would recognize it and whatever, it wouldn’t be that different than what you’re used to. But in our local little town, there was an old theater that we used to go to and watch horror movies in. They never had like real release movies or whatever. It was just a bunch of kids being silly. And they would have old movies or whatever on Friday night we’d go watch a movie. So, I had never been on a field trip to the movie theater. That was weird. So they loaded us up on these buses ‘for a field trip, and they took us across town, which is only about three miles to the theater, this local theater. And the movie they were playing was 1776, which is the old, uh, you know, celebration. We have the Decoration of Independence written, there’s a Broadway play, whatever. And I know you’ve, you’ve seen that. Um, and so, you know, it was just teaching us about the history and all. So we get on the bus and I’m thinking, oh, this will be cool. It’s better than sitting in math class or whatever else. And they put us on each bus, not segregated. My bus, whatever bus I was on, wasn’t old 29 was my class. Whatever class I was in, which was fully integrated, probably about 40% black, 60% white, thereabouts, fairly even. And so we go to this place the, to the movie theater. And I was thinking on the way over there, you know, I’ve never seen any black kids at the movie theater. That’s a white kid thing. I’ve never seen any of ’em there. That’s, so I wonder if any of these kids have ever been there. So when we get to the movie theater, I’m expecting to go in the front door and sit. They have these old wooden chairs that are in rows, you know, the old-timey kind of chairs by today’s standards, not a lot of padding or whatever else. And the place isn’t real fancy, but the chairs were sturdy and, you know, everything was, was, um, simple but fine. But when, when I get there, they redirect us through this side door to the movie theater that I had never been, and didn’t even notice was there. So we go in and I’m thinking, why are we going in? There’s a lot of kids there. They got, you know, two class loads, probably 250 kids there. And, um, I’m thinking, where are they taking us? I’ve never been in this door. Don’t know. And as I go in, I start going up this narrow stairway, it’s really narrow. And so we go stomping up there and I’m just following the leader. And when I get up there, I realize there’s a balcony to the movie theater that I never knew was there. And I’ve sat in the bottom before, never looked up, never knew there was a balcony there. And so I go on up and sit down. There’s probably enough, maybe for my class, so maybe 25, 30 students, something like that. Maybe. I’m not exactly sure. It’s been a while. But anyway, I start to sit down and my chair is broken and it kind of folds back. I’m thinking, geez, I can’t sit here. And I tell the teacher who’s with us, my chair’s broken, and she’s a black teacher and she says, just sit there, you’ll manage, you’ll manage. And all the other kids sit there too. And next to me is a girl, a black girl who I’m still friends with. Bessie Williams is her name. And I look at Bessie and I say, my chair is broken. I don’t know if I can sit here through the whole movie. And she looks at it and says, well get used to it. That’s what we deal with all the time. So I didn’t know it, but the whole time that me and all of the other white kids in town are sitting in the bottom of the theater, the black kids are in the balcony with the broken chairs remaining fairly quiet if they can afford to see a movie at all. But there was no sign that said blacks up, white’s down. It was nothing like that. It was just understood that’s the way it had always been. And so, you know, I sat through the movie and it’s interesting, the movie is, has a big part of the movie when they’re trying to do the declaration and they’re debating slavery as to whether they should outlaw slavery and the Declaration of Independence. And they’re singing songs about it and drowning on and on, and finally putting the issue of slavery aside so that they can have, you know, um, unanimity among all of the founding fathers, all white fathers, of course. Um, and they put slavery aside. And here I am in the balcony of a rural movie theater, 200 years later. And to some extent, we’ve still put the issue aside.

Q: So there was also sort of complacency among everybody because that’s just kind of the way that it had always been?

A: That’s Correct. And it, it took time. There were, you know, I would say that blacks and whites had kind of come to a conclusion about how things worked, whether they should work that way or not work that way or whatever else. But I think the interesting thing about my generation and particularly my school year, I think it gave us the chance to, uh, reset expectations on how things were going to work. And it took a while. It did, because of course we were young and there were other people in charge of things.

Q: So, both of those stories were kind of about you going, like in your younger years of school, like, um, elementary and middle school, how did sort of race relations evolve as you got into high school in the late seventies, early eighties?

A: So I think when, by the time I got into high school and my class, and even my brother’s class who’s two years older than me, we started resetting some of those, uh, historical precedents, I would say, or trends or characteristics or whatever. As an example, when the schools integrated, it’s easy enough to say we’re gonna put ’em all in the same class. They did things to help bridge to transition. Like for instance, when I went to the first grade, the year before, if any student was given a first-grade teacher, they would’ve been all white, of course. And, um, you had that teacher all day long, they taught it’s first grade, so they teach math and teach math and reading and everything all at once. But now you’ve got black kids and white kids in the same class. So they changed it so that I had two first-grade teachers and I would, they were right across the hall from one another. So I would spend the first half of the day with Mrs. Baggott, who happened to be black. And Mrs. Fortenberry was white across the hall. And I would go into her class for half the class too. So we each had black and white students, uh, all through high school. Well, not, some of this was still in place as I graduated high school, although the students actually killed some of it. For instance, you have the homecoming queen. It’s a big football game, right? Well, is the homecoming queen going to be black or are they gonna be white? Well, in 1971 when the county was about 65, 60 to, well, 60 to 65% white and the other percent black, that would’ve been reflected in the student body of any given class as well. There was never going to be a black homecoming queen in those years. It wouldn’t have happened. So they changed the rules and they had a black homecoming queen and a white homecoming queen. And we voted for both. I got to vote for both queens, black and white, but all the ones running for black were black. All the ones running for white were white. We didn’t have to worry about Jewish people and Muslims and all the other, we didn’t have those people in rural Mississippi at the time. You were black or you were white or you were Tim Smith, whose mother happened to be from Spain, and he was Catholic, he was unique. That’s the only Catholic student in my high school. Um, but we treated him as though we, he was part of the white group, right? He happened to be Catholic. So any case, by the time I got into high school, there were still several of those things. One of them, how do you deal with the homecoming dance. Now you got white kids and black kids dancing together in 1979? No way that was gonna happen. So the solution was easy till the homecoming dance. And there was not a homecoming dance between 1970 and 1980. During all of those years, there was never a school dance whatsoever until I got to be in the 10th grade and my brother was a senior. And we started calling BS on that and said, why is it we can’t have a, um, you know, a homecoming dance because of these old archaic rules and stupidity that was created many, many years ahead. Now, the school buses were still black and white, even all the way through high school. They had never changed. We had the first integrated homecoming dance in 1980. Now, interestingly, we actually had to have two because all the white kids wanted to dance to rock and roll, and all the black kids wanted to dance to soul music or R&B. So we had two, but all of the kids went back and forth between ’em. They weren’t very far apart. So they just kind of went back and forth depending on what kind of music you wanted to dance to. By the time I got to be a senior, even that was done. It was just one, and it played all kinds of music or whatever. And so, um, even that had had kind of died off at that point.

Q: So, it sounds like the fact that there were two homecoming queens, it was, it was sort of like the answer to the inequality and division was sort of more division because there was the black couple, the black homecoming king and queen, and then the white homecoming king and queen.

A: So it was kind of, that seems a little bit. Yeah, it was, uh, I don’t know what of a better solution for that time would’ve been. I mean, we can easily look back now and say, how stupid was that? But at that time, given emotions given everything else that was going on, I did think it mattered that the white kids voted for the black homecoming queen and the black kids voted for the white homecoming queen and student. There was one student body president who turned out black or white, and actually kind of flip-flopped back and forth. It never seemed to be a problem. And so it, when I got into my senior year, I had a friend, her name is Shelly, still a friend today. She’s white, happens to be. But I had a lot of black friends too, and her and a few of the other girls, the town girls, right? Not my rural farming community, but the town girls, their mothers got together and decided we’re gonna have a party for our girls or about five of ’em as I recall, roughly five. And we’ll invite all of their friends and we’ll have a pool party. And one of ’em had a swimming pool. And so they came to us, Shelly came to me and said, my mom and the other moms were having this party and want you to come. And I said, absolutely, you know, be there. And she also went to James Hill and Bessie Williams and Angela Middlebrook and Sonya Lewis and said, Hey, we’re having this party. We’d love to see you. You know, it’s on this day. You’ll get a formal invitation, whatever else. Well, those kids happen to be black. And then the moms found out that Shelly had talked to all of these black kids and said, well, we’re having a pool party. You know, however, they said it as politely as southern ladies can be polite, not necessarily nice, basically told Shelly, go back to school and tell ’em all they can’t come. And so Shelly came to me first and said, I, I just don’t know what to do. I, there’s no way I can tell Sonya and Bessie and these others, they can’t come to my party. There’s no way I’m gonna do that. I’m just going to tell ’em I’m not gonna be part of the party. And I said, you don’t do that. Let me do that. And so I’ll go to all the white kids, I’ll tell the black kids what’s going on. I didn’t hide it from ’em, but I told all of the other white kids we’re not going to their party. And it’s nothing to do with the daughters, it’s all to do with the mothers. And so we sent the message back, no we will not be there until finally they changed their rules. I think they were a little embarrassed about the whole effort, um, and changed the rules and said, no, everybody that Shelly and the others want to come will be there. And they were there. We’ve then sent the word out. No, they’ve, they’re contrite and they’ve apologized and so we’re all gonna be there. They changed that and uh, we were there. It was a great party. And I would guess, um, Lawrence County’s never had that problem again, ’cause I think the message got out-don’t be stupid about such things. It causes problems for people. We all got along and here intrusive mothers are driving wedges between us based upon rules that we didn’t have anything to do with creating, nor certainly any interest in propagating.

Q: Well, I mean, you’ve talked a lot about how you were on the football team and a bunch of your teammates were black and it just didn’t, like, it was just not a thought.

A: Generally not now on a serious level. Now on a joking level, that was constant teasing and whatever. My last name is Blackwell. So the black kids gave me a nickname and it’s “n-word”-well. And that was my nickname to the black kids. They called me that pretty much on the football field all the time as a joke, a friendly joke. The white kids picked up on it. Even a couple of teachers picked up on it. And they started calling me that too. I don’t think that would go today. But at the time it was kind of funny. And, um, I don’t know, we just all, I can’t say we always got along, uh, based upon, you know, racial issues. But there was a lot of joking around about it. There was a lot of things like we would tease them about their music and they would tease us about ours and, they would all, you know, accuse us of being rich cause we were white when it wasn’t really true. But more than likely, we were a lot richer than most of them, things like that. They had their own football teams. There are the black, traditionally black, colleges in Mississippi and the South, Alcorn and Jackson State and so forth. And the black kids, they all kind of followed those football teams. Whereas, you know, the white kids never followed those that closely, they do today actually. But, never followed them that closely, but followed Ole Miss, Mississippi State, those types of schools which have a lot of black kids, but are predominantly white schools. So anyway, there were differences between us all, but we just kind of found ways to work. I always thought this way as I got older, southern people generally preach a lot about religion, about friendliness, about hospitality. And they do that at home while they ignore these other historical divisions that have happened over the years. But when you do that at home and you tell a kid, you be respectful to your elders, you be nice to people, you be honest, you be friendly and hospitable, and then they go to school. Um, many of the things that come from others that create division pale in comparison to what was taught at home. And they, small kids won’t distinguish between black and white or any other kind of divisions that a society has to deal with. So to me, that is the key to everybody in the world kind of getting along, is teaching those basic principles at home. Unfortunately, sometimes parents are racist or bigoted, or otherwise biased, and it translates to their kids. If they inadvertently teach the principles that will overcome those biases in future generations, they will be much better off.

Q: So, how much did you learn about black history in school? Like, um, how much did you know about people like Martin Luther King, people like that?

A: We, every year first through 12th grade, we always had some form of a social studies or a history class, one or the other, sometimes maybe both, I’m not sure. Not once in first through 12th grade did we ever study Martin Luther King. Not once, never learned anything about him in school. I don’t know, for one thing, the school system was so bad that you’d get a book for American history that would start in, you know 1492. And the teacher or the school system was so bad you never got to the 1960s most of the time. You just never covered that far. You’re lucky to get to World War II, but then there’s probably some element of avoidance too. Just avoid the topic that has caused friction. Um, and, and, and there was friction, I didn’t necessarily see it, but many of the students in my grade, in the first grade, their parents took them out of the school system rather than send them to first grade with an integrated school system. And they created their own school systems in South Mississippi. Many of them are still there, but they were whites only and they were private. You had to pay to go there. And they over with a few notable exceptions, they were really bad school systems. They were underfunded and just full of people who had really no interest in education. They were all just about bigotry and segregation. So there was all of that friction over time. Most of those died and integrated back into the regular school system. A few of them that were very well known still exist today, but they’re integrated. One of them is Park Lane Academy. It’s where Britney Spears went to school, close by my house. But when she went there, it was segregated. It was all white. And today, it’s not. And I don’t think there’s a segregated school system in Mississippi by design. There might be some accounting that’s just like overwhelmingly black or overwhelmingly white. But, um, they would accept a black kid or a white kid in any school in Mississippi today, without a doubt. Those segregated school systems just died of their own stupidity over time. I can tell you one more story.

A: Go for it.

Q: So in high school, in the 10th grade or 11th grade, I think it was summer before the 11th grade, I got a, a job, summer job and a little, um, it’s a kind of like a general store, but it did sell a lot of auto parts and other kinds of stuff like that. It’s called Western Auto. It doesn’t exist anymore as far as I know. But it was a small country store in town and I, you know, worked at the counter and I would put together bicycles that we were gonna sell and change cars, tires and whatever else. So just kind of a general dude there. One day this grandmother, black grandmother comes into the store and with her grandson, who was, I would say probably about seven or eight. And it became clear as she talked to me that he had worked, it was a late part of summer. He had worked all summer long, saving money from cutting grass. So he run a lawn mower, get five bucks back then, and saved all this money. And he was coming in to buy a bicycle. And so as I was showing him the bicycles, he finally picked out one that he wanted. And then over on the side there were these racks of accessories for bicycles. There were reflectors and horns and flags and all this junk that you could attach to your bicycle. He picks out his bike and then he starts picking out all of the accessories that he was gonna put on this bicycle. And he had all of the flags and reflectors and everything, horns and I don’t know what all little signs and whatever. And so he piles them up on the counter and I start ringing it up. And as I suspected when he did, he didn’t have enough money to buy the bicycle and all of the accessories. So I started talking to him. He was like seven or eight years old, something like that. So I started telling him, well, you can’t get all of these accessories, but if you get the bike, you can get that flag and this reflector and this horn or whatever, and it’ll work. You’ll be able to buy it. And he started crying and he said, I just, I can’t do that. All the kids in my neighborhood have all kinds of reflectors and everything on their bicycles, so I need those first. So the kid bought all of the accessories and left the bicycle. Now I tell that story because I looked at it and I said, the likelihood of his grandmother, who in 1980 was probably 75 years old, the likelihood she had a real education to be able to kind of work and educate this kid on her own, was probably pretty low. And also the connotation among the black community at that time was that, as I put it, seeming to be rich or successful or wealthy, as in this kid’s mind reflected in reflectors and flags and horns and bells, uh, outpaced the actual bicycle itself, the ability to ride and go. And so it made an impression on me that what was the likelihood a white kid would come in and do the same thing. It was very low, but it wasn’t inherent to his race. It was inherent to the situation that he had to grow up in, in rural, poor Mississippi. I felt sorry for him, I actually started to give him the money, which I didn’t have a lot of money myself, but I thought, no, I would have probably insulted his grandmother if I did. But if, if I’d given him another $15, he probably could have gotten the bike.

Further Research

ALVIN B. RUBIN, Circuit Judge: and Circuit Judge [70] PATRICK E. HIGGINBOTHAM. “United States v. Lawrence County School Dist.” Legal research tools from Casetext, September 15, 1986. https://casetext.com/case/united-states-v-lawrence-county-school-dist.

Bolton, Charles. “The Last Stand of Massive Resistance: Mississippi Public School Integration, 1970.” The Last Stand of Massive Resistance: Mississippi Public School Integration, 1970 – 2009-02, 2009. https://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/the-last-stand-of-massive-resistance-1970.

Domonoske, Camila. “After 50-Year Legal Struggle, Mississippi School District Ordered to Desegregate.” NPR. NPR, May 17, 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/05/17/478389720/after-50-year-legal-struggle-mississippi-school-district-ordered-to-desegregate.

Pittman, Ashton. “Hyde-Smith Attended All-White ‘SEG Academy’ to Avoid Integration.” Hyde-Smith Attended All-White ‘Seg Academy’ to Avoid Integration | Jackson Free Press | Jackson, MS, 2018. https://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2018/nov/23/hyde-smith-attended-all-white-seg-academy-avoid-in/.

Leave a Reply