By Myra Naqvi

Newspaper article detailing the boycott of the New York AC track meet in the Philadelphia Inquirer, 1968, courtesy of ProQuest

Craig Nation was twenty-one years old when he and his teammates at Villanova University decided to boycott the New York Athletic Club’s indoor track and field meet in 1968. The meet was supposed to mark the 100th anniversary of the first indoor track meet in U.S. history and was expected to be the highlight of the indoor season [1]. Not to mention Villanova was the reigning NCAA champion. While it was a prestigious event, the NYAC prohibited black and Jewish membership, continuing segregationist policies that were supposed to have been abolished four years prior [2]. Nation remembers making the decision to boycott the meet with his team and how a year later, the NYAC was no longer a segregated organization. He describes the event as a “great, great thing which we accomplished as a team, or made a contribution to as a team. All of this put together in the context of the time made it a special sort of thing. I can say it’s still a big point of pride” [3]. In his book American Dreams, historian H.W. Brands details the rise of spectator sports in the 1950s and the subsequent use of athletics as a means of protest [4]. Craig Nation’s experience as a college athlete in the 1960s reflects Brands’ description of the slow dismantlement of the Jim Crow System and the power of protest in sports as a mechanism for change.

The NYAC boycott was part of a greater movement led by Dr. Harry Edwards and the Olympic Project for Human Rights, who sought to boycott the 1968 Olympics in protest of human rights injustices within sports [5]. While the boycott did not fully materialize, Olympic medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in protest of inequality in what Brands detailed as “the action that garnered the greatest attention for the black power movement” [6]. Nation recalls that the day after Tommie Smith and John Carlos podiumed in the 200 meters, his teammate and friend Larry James won gold in the 4 x 400-meter relay, and silver in the open 400 meter. He remembers that “Larry and his teammates were under terrible pressure to do something [like Carlos and Smith had” [7]. But Carlos and Smith were thrown off the Olympic team and sent home, putting Larry in a difficult place. Larry and his teammates “went for a slightly more modest form of protest by wearing black berets on the podium” [8]. Nation explained that people competing at such a high level of competition “had choices to make about how to comport themselves. They could use the stage or abuse it. It was a difficult, personal choice. Yet sometimes it was an opportunity” [9]. While H.W. Brands addresses the impact that protests in sport had on the Civil Rights movement, Craig Nation’s first-hand account and connection to the NYAC and Olympic protests provide humanity and complexity to the issue.

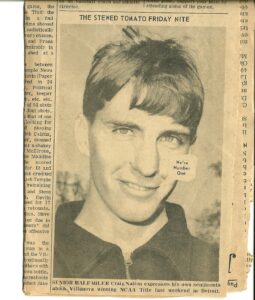

Craig Nation expressing his excitement after Villanova won the 1968 NCAA championship, The Villanovan, Courtesy of Craig Nation

Across the nation and on the international stage, black athletes faced persistent discrimination on and off the field, but Craig Nation did not recall having any problems at Villanova University. He remembers feeling like he was in a “fully integrated harmonious environment” [10]. Nation and Larry James were teammates at Villanova. In fact, he was James’ mentor when he joined the team in 1967. Nation described James as a “great, great American track and field runner. An Olympic gold and silver medalist and world record holder… Just great. I was his mentor. Black, white, no issue. No question” [11]. Nation was always impressed that on his team they had “a very positive atmosphere in a day and age when it was really difficult, when there was a lot of tension” [12]. Of course, this was not the case at every university. For example, the Southeastern Conference did not begin to integrate until 1966, and the University of Mississippi was not fully integrated until 1971 [13]. A common phenomenon in the south was that black athletes were hated throughout the day but celebrated under the lights. This caused many black athletes to become nonpolitical to avoid confrontation and violence from their white counterparts, which ultimately emboldened universities to continue to uphold racist practices that would allow the edifice of the Jim Crow System to survive, even after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1965.

On April 4th, 1968, Martin Luther King Junior was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. That weekend, the Villanova team was scheduled to travel to Knoxville to compete at a meet hosted by the University of Tennessee. Back in Philadelphia, Nation’s team gathered for a team meeting to decide whether they would compete in the meet. Nation remembers that on his drive to the meeting, “there were a lot of African American people on the street. They were very upset, and for a good reason. A group of people for around my car and started to pound on it. I tried to show solidarity and continued to move throughout the crowd. Nobody did anything. They were just expressing their anger” [14]. After making it to the meeting, his team voted to go to the meet. Nation remembers that their flight to Tennessee flew over Washington, and “through the air it looked like the whole city was on fire” [15]. He explained that “it was a very striking thing to see. I was twenty-one years old trying to put it all together” [16]. Nation’s experiences as a student-athlete at Villanova in the late 1960s illustrate how the Civil Rights Movement impacted the everyday lives of American citizens, like Brands alludes to throughout his novel.

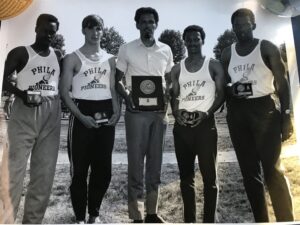

The Philadelphia Pioneers after winning 4 x 400 at the AAU national championship, courtesy of Craig Nation

Upon his graduation from Villanova University in 1968, Nation began a new running career with a local track club, the Philadelphia Pioneer Club. The Philadelphia Pioneer Club was a historically black segregated organization, but in the era of desegregation, Craig Nation became the first white person to join the team. He remembers how interesting and eye opening it was to cross the color line and immerse himself in a culture that he was unfamiliar with, “to see the world the way the other side sees it” [17]. While Villanova’s head coach, Jim Elliot, was in full support of integration, not all of Nation’s coaches were in support of him joining the Philadelphia Pioneers. Nation remembers some of his coaches saying, “well what are you doing that for? Why are you running for that club?” [18]. While he was fortunate that his experiences at Villanova were mostly positive in regard to race relations, Nation acknowledges that “not everybody was on board for change,” yet that “segregated track and field, segregated sporting culture seemed so ironic” [19].

In his chronicle of American history since 1945, H.W. Brands illustrated the complexity of history by detailing the American pursuit of democratization and development abroad contrasted with the ongoing battle over race relations at home. While he briefly mentions the impact that sports had on the Civil Rights Movement, Craig Nation’s experience as a student-athlete in the late 1960s gives humanity and perplexity to the issues being faced by everyday people. His account proves that “nobody was immune, and certainly not collegiate athletics. You had to deal with the issue in some way. Either by self-consciously ignoring it or by engaging with it. Either way, you had to do something” [20].

[1] “Boycott may End NYAC Track Meet,” Chicago Daily Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1966-1973), Feb 03, 1968. [ProQuest]

[2] Dexter L. Blackman, “’RUN, JUMP, OR SHUFFLE ARE ALL THE SAME WHEN YOU DO IT FOR THE MAN!’: The OPHR, Black Power, and the Boycott of the 1968 NYAC Meet,” Souls 21 no. 1, (2019), 52-76. [Taylor and Francis Online]

H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945, (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 127.

[3] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[4] Brands, American Dreams, 74-76.

[5] Nikole Tower, “Olympic Project for Human Rights lit fire for 1968 protests,” Global Sport Matters, (2018). [Web]

[6] Brands, American Dreams, 152.

[7] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[8] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[9] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[10] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[11] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[12] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[13] Matthew Wills, “The Uneasy History of Integrated Sports in America.” JSTOR Daily, (2017). [JSTOR Daily]

[14] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[15] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[16] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[17] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[18] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[19] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

[20] Interview with Robert C. Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

Appendix

“The second shortcoming of the Brown decision was that it applied only to schools […] Segregated public schools were an important pillar of the Jim Crow system, yet the edifice could survive without them. The much larger realm of segregation remained untouched.” (H.W. Brands, American Dreams, p. 86)

Interview Subject

Robert C. Nation, age 77, Dickinson College professor who ran track and field for Villanova University in the late 1960s and witnessed the slow desegregation of sports.

Interview

Interview with Professor Craig Nation, Carlisle, PA, November 20, 2023.

Selected Transcript

Q: Can you tell me a little about the culture of your team at Villanova as it pertained to race relations?

A: “I have always been impressed with Villanova as a model for what a collegiate athletic program can be. Our coach, Jim Elliot, left no doubt about priorities. Your first priority is to be a student. To learn, to grow, to educate, to mature. And then comes track […] I think we probably managed to have a successful team at the highest level of competition without sacrificing any principles or priorities. That was that was good.”

“Race relations were very interesting. I can’t speak for everyone, but I can say what I remembered. We didn’t have a problem at Villanova with race relations. In this era. I was at Villanova from 64 to 68, so this is the height of the civil rights movement. Intense engagement.”

“I never perceived it as an issue in my environment I felt like I was in a fully integrated harmonious environment, that’s the way I perceived it.”

“I think my junior year the way we did it was a team member was assigned to a first year as a mentor. I was assigned to Larry James. He was a great, great American track and field runner, Olympic gold medal, Olympic silver medal, world record holder, just great. From White Plains, NY. I was his mentor. Black, white- No issue. No, no question. It always impressed me that on our team we had a very positive atmosphere in a day and age when it was really difficult, when there’s a lot of tension.”

“My senior year, my black teammates raised the issue that track was in many ways still a segregated sport. And one of the biggest track and field organizations was the New York Athletic Club which hosted a big indoor track meet every year. But the NYAC was a white only organization, not just the meet, but the organization. So, as national champions, we said we wanted to boycott this meet. And we had a big discussion about it as a team. We decided unanimously to boycott and not low and behold it the next year the NYAC was no longer a segregated organization. It was a great, great thing. Which we sort of accomplished as a team or made a contribution to as a team. All of this put together in the context of the time made it a special sort of thing. It meant a lot to me that we could do that. I can say it’s just still quite a big point of pride. It’s like 50 or 60 years ago or something like that.”

Q: Was your coach supportive of your team boycotting the meet?

A: “Absolutely. Although I had more than one coach, and not all of them had… like when I went to run for the Philadelphia Pioneers some of them said “well what are you doing that for? Why are you running for that club?” This was part of that time; those perceptions were out there. Not everybody was on board. It was a battle in some ways, but in sporting culture it seems so ironic. Segregated track and field…” (15:15)

“My senior year in 1968 was the assassination of MLK. That weekend we had a track meet at the university of Tennessee- where MLK was assassinated. We had to have a team meeting to decide whether we would go. There were a lot of African American people on the street, they were upset for a good reason- they got around my car and started to pound on it. I tried to show solidarity and keep moving. Nobody did anything, they were just expressing their anger. I got through and made it to the meeting, and we voted to go. We flew down to Tennessee. I remember our flight flew over Washington; through the air it looked like the whole city was on fire. It was a very striking thing to see. I was 21 years old trying to put it all together. Those are all my experiences as an athlete at Villanova.”

Q: Today it feels easy for college students to disengage from current events and remain protected in a “bubble.” Was everyone engaged? Were the opportunities to remain passive in this time?

A: “Nobody was immune, and certainly not collegiate athletics.”

“You couldn’t dodge the issue. You had to deal with it in some way. Either by self-consciously ignoring it or hunkering down or engaging with the issues but you had to do something like that.”

“I don’t think the majority was all that engaged back then either- when you look closely maybe it’s not as different as you think (the generations)”

“There was then too a lot of disengagement.”

Q: Were you and your teammates moved by the demonstrations of the 1968 Olympics?

A: “Larry James was also involved in [the 1968 Olympics] because John Carlos and Tommie Smith had their dramatic demonstration, fist raised all that, and then the next day, Larry and his teammates won the gold medal in the 4×400, so they were under terrible pressure to do something like that. Remember, Carlos and [who] got thrown off the team, it was awful, they were sent home with gold medals around their neck because they took a knee basically. They didn’t hit anybody in the head. So then Larry and company, he talked to me about this in great detail, they didn’t know what to do. Larry was one of the leaders of this movement and demonstrations at the Olympic games, and he was the best athlete too, so he had a lot of prestige, everybody admired and respected him. And I was supposed to be his mentor [laughs] So they went for a slightly more modest form of protest. They wore berets black berets it was a a more temperate version of Carlos and Smith. The people that engaged in those activities had choices to make they were making risks. […] All of these people had to make decisions about how to comport themselves. They can use the stage or abuse it. How to represent the causes they believe in. It is a difficult, personal choice. Sometimes it can be seen as an opportunity.”

Further Research

Fraser, Gerald C. “Black Athletes Are Cautioned Not to Cross Lines.” The New York Times Company. (1968). Olympic History (nytimes.com)

“1968: Mexico City. Black Power Struggles.” The New York Times Company. (1968). Olympic History (nytimes.com)

“Tommie Smith and John Carlos Raise Their Fists at the 1968 Olympics.” History.com, A&E Television Networks. (2021) https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/black-power-salute-1968-olympics

Wills, Matthew. “The Uneasy History of Integrated Sports in America.” JSTOR Daily. (2017) The Uneasy History of Integrated Sports in America – JSTOR Daily

Spivey, Donald. “The Black Athlete in Big-Time Intercollegiate Sports, 1941-1968.” Phylon (1960-) 44, no. 2 (1983): 116–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/275023.

“Sports- Levelling the Playing Field.” National Museum of African American History and Culture. Smithsonian. Sports | National Museum of African American History and Culture (si.edu)

Reese, Renford. “The Socio-Political Context of the Integration of Sport in America.” Journal of African American Men 3, no. 4 (1998): 5–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41819345.

Sellitto, Anthony. “Villanova Track and Cross Country Teams 1966 1967 & 1968 NCAA Champs.” YouTube. https://youtu.be/l2yHIZlM-dI?si=KW45RbtbKwQpCfcK.

Leave a Reply