A Truly Nuclear Life: Growing Up as a Woman in 1950s Utah

By: Olivia Whittaker

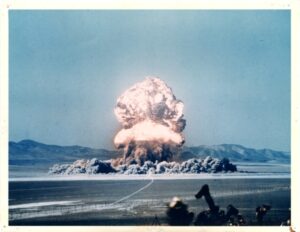

On January 27, 1951, residents of Milford, Utah and others first stood outside to watch the brilliant white flash of a one-kiloton bomb fill the western sky. It was the first atomic bomb test of the Nevada test site, around 250 miles away. They watched for a moment in awe what would soon become routine to the rugged little railroad town.

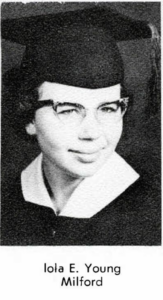

In his book American Dreams, H.W. Brands characterizes 1950s America as an age of new technology, consumerism, and middle-class prosperity. He paints a picture of American suburbia where men work, women tend to homes and children, and families enjoy car vacations, football games, and TV dinners.[1] While not inaccurate, Brands’ overview is general and limited. There are several critical aspects of American life in the 1950s that he omits, such as the instrumental roles of gender, religion, and nuclear threat. Examining the experience of one Iola Whittaker, a teenaged girl living in the small Mormon town of Milford, Utah in the 1950s, provides specific insight into these facets of life not meaningfully explored by Brands, revealing the more complex, and sometimes darker reality of nuclear life in the western United States.

Nevada Test Site bomb test, circa 1960s. Courtesy of Oregon State Special Collections &; Archives Research Center

Wind from the West, Storm from the East

In the late 1950s, the National Election Study found that about 73% of Americans trusted the government— more than three times the current level.[2] Americans of this decade were faithful that their leaders would act in their best interests, and most took the government at its word. So, when the United States Atomic Energy Commission promised safety to the public as they began testing atomic bombs in Nevada in 1951, the public believed them. From 1951 to 1992, the commission would run 100 atmospheric atomic bomb tests that could be seen hundreds of miles out, including by Milford. “There would just be absolute white-out in the atmosphere,” Iola recalls.[3] She even describes how residents would “go out and sit on [their] porches” to watch the big flash. They knew when the tests would occur, as the times would be announced in the newspaper or on the radio in advance.

What wasn’t mentioned, though, was that the wind would carry radiation out east to towns like Milford, putting potential millions at risk of thyroid disorders, genetic mutations, respiratory diseases, infertility, and life-threatening cancers.[4] Not only was the Atomic Energy Commission aware of the danger years in advance, but actively lied in their press releases, ignored the cautions of scientists and researchers, and even forced their own scientists to falsify field reports to deny any adverse effects of the tests on nearby livestock, which had suffered countless burns, malformations, and fatalities.[5] “They just didn’t tell us what their research was showing,” Iola says, “and in the meantime, people were starting to get sick.”[6]

But to the commission, this was simply the cost of communist containment. The importance of bomb testing was stressed throughout the government. In a 1956 issue of Milford News, Utah representative Henry Dixon was quoted saying: “We cannot jeopardize our present commanding lead by halting tests so vital to the development of modern weapons without being absolutely sure that the Soviets would do like-wise,” in response to one congressman’s proposal to halt testing as a “prelude to disarmament.”[7]

Cold War anxiety cast a continuous shadow over even the sunniest of American suburbia. On Saturday mornings, Iola and her family listened to the radio program I Was a Communist for the FBI, which emphasized the danger that communism posed to the United States. In school, Iola and her classmates participated in regular “Duck and Cover” drills, where students practiced taking cover under their desks in case of Soviet bombing. But while Cold War fears were more tangible to adults (who paid attention to politics), children didn’t seem to pay them much mind. “Kids kind of gloss[ed] it over,”[8] Iola says. She compares the bomb drills to fire drills, routine and mundane. Though she does recall a chilling moment in March of 1953, when she discovered that the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had died: “I remember being in eighth grade … the only thought I had [was]: ‘Oh my God, could there be something worse coming’?”[9]

Nice and Quiet Girls

Despite 1950s America being distinct for its stark gender roles (think: the endlessly parodied “1950’s housewife”), Brands’ American Dreams lacks attention to the experiences of women and the impact of gender norms throughout the decade. Even though Iola was often comfortable with a more traditional lifestyle, cultural ideas about gender critically shaped her life and environment growing up. The influences could be silent, as with the activities and subjects she was pushed towards in school; and when it came to issues of sex and even domestic violence in her town, it was less about what was said or done, and more about what wasn’t.

Iola had never noticed gender disparities in her early childhood. “We were kids outside playing in those early years.” she says, “…some of my best friends were the boys that I had grown up with.”[10] But as she entered high school in 1954, that was about to change. She could no longer play alongside her male peers, as gym classes were segregated by gender, and girls were barred from several of the sports enjoyed by boys. She describes this as her “first questioning,” saying: “As girls, we started to question, you know: ‘well, how come at school we can’t do track?’”[11]

As it was generally assumed that girls would one day become homemakers, the school prioritized teaching them skills like cooking and basic sewing— all girls at Iola’s school were required to take home economics classes. Iola hated them. She found the classes confusing and had no interest in sewing (or wearing) aprons; but as a girl, there was simply no way out of it. So, she put her head down and did the work she had to do. The highly gendered culture of Iola’s school and town was a product of its time to be sure, but it was especially informed by the Mormon church. “They set the religious code,” she says.

Sexual abstinence was a major part of that code. Iola remembers that “health [class] was always taught by the football coach… and believe me, you did not learn very much in health, especially you never learned anything about women’s health.” Menstruation “couldn’t even be mentioned,” and “abstinence was… pretty much the first sentence of any speech.”[12] Topics of sex, sexuality, or even reproductive health were taboo, and silenced within the Mormon culture. But as some women in Milford knew, that silence could come at a grave cost.

As a child, Iola wasn’t aware of the abuse occurring in other girls’ homes. She recalls about one girl who was younger than her: “we thought gosh, she’d have bruises on her, [but] never, never even thought about that her father was an abuser. And he was, but nobody turned him in.” As she got older, she realized that there were several men in her town who abused their wives and daughters. “Other men knew it,”[13] she says, but they said nothing. In her later teen years, Iola “started to put two and two together.” She confronted her father, saying: “How dare you men not… do something about this???” But this only angered him. “This is just the way the world is,” he replied dismissively.[14]

The Mormon Way

The Mormon church would not protect women against sexual abuse, but in the late 1950s, it began to concern itself with a different kind of “sexual deviancy.” In 1958, Bruce R. McConkie published Mormon Doctrine, the first general authority-authored book to explicitly condemn homosexuality. McConkie placed homosexuality among “Lucifer’s chief means of leading us to hell,” along with other such offenses as rape and infidelity.[15] The book was widely received as representing the official stance of the church, even if it was not actually endorsed by it. Of the more religious people in town, Iola says that “…they felt like [homosexuality] was a mortal sin, that it could be corrected, and that people should work hard in having it corrected.” Though she herself disavowed this belief, saying: “The sin of it was that people acted so awful about it.”[16] There were a few gay people in her life, including friends of her aunt and even a high school classmate. “We never worried about it,” she says. Iola and her family didn’t think one way or another about queer people, but their feelings were not shared by the whole community.

Iola was always an outlier in her religious town. Unlike almost everyone else, she never believed in the Mormon doctrine. She describes religious differences as a “topic of contention” in Milford.[17] Her peers were often discomforted when they found out that she didn’t share their beliefs. Iola even remembers some people acting confused that her and her sisters were so nice despite not being Mormon. But Iola always found the church’s teachings difficult to believe, and found the many religious superstitions people held especially irritating. In one anecdote, she remembers working on a sewing project when a girl told her: “You know every stitch that you take on a Sunday is like…putting the nails in Jesus.”[18] And it wasn’t just Milford that was saturated in LDS Ideology—when Iola’s sister, Thea, moved with her husband to just outside of Salt Lake City, their town kept a list of homes that were not Mormon, which Iola characterizes as “discrimination.”[19]

What She Wants

Being non-religious was not the only way in which Iola pushed what was expected of her. When she became a young adult, her father wanted her to enter secretarial training, as was common for women. But Iola wasn’t interested in secretarial work. As she put it: “I didn’t want to just go sit at a desk and take stenography…And my dad was encouraging me to do that because he was of that “old white men knew better” sort of [ideal]. And so if you wanted to have a woman have employment, they were either teachers, nurses, or stenographers.”[20] Instead, Iola wanted to go to college, but it took some convincing to get her father on board. “He probably took a deep breath,” says Iola, “he was probably talking to my mom who would talk to her sister that was in the town that had the college, and they convinced dad that, ‘okay, you know, she can do this.’”[21]

Iola Whittaker (Then: Iola Young) in Snow College yearbook, 1960. Courtesy of Snow College Digital Collections

But although she took control of her future by pursuing an education, Iola never considered herself a feminist. To her, the feminist movement occurred in big cities. It was women challenging the status quo by breaking into fields like law, marching in the streets, and taking political action. Iola respected those women and considered them brave, but she mostly only saw them on television, and only when she was older, during and after college. “It was not a movement in Utah,” she says.[22] And besides, like most women in her environment, Iola married in college and dropped out to support her husband. She had kids and worked as a secretary in his department while he completed his graduate program. But Iola was happy. She loved her husband and kids and wanted to support them. “You know, I really have to say I think we worked together,” she says, “You know, it wasn’t like: ‘oh gosh, Mack, I wish…we were making more money’ or things like that. That was not our prime target… I wanted the marriage, I wanted the children, I knew what I was going to have to do, you know, to make a life for all of us, and it was okay at that point.”[23] By a more modern view, Iola could easily be considered a feminist simply by building the life she truly wanted for herself and by respecting the rights of other women to do the same.

While H.W. Brands portrays the 1950s as an era of prosperity, consumerism, and traditional family life, the lived experience of Iola Whittaker tells a more complex story. Her life in Milford, Utah—shaped by nuclear fallout, gender roles, and an oppressive religious culture—exposes gaps in and expands upon Brands’ description. Iola’s unique perspective reveals a side of 1950s America that Brands’ broad narrative overlooks.

[1] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin, 2010), 70, 80.

[2] “Public Trust in Government: 1958–2024,” Pew Research Center, accessed May 2025, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/06/24/public-trust-in-government-1958-2024/.

[3] Iola Whittaker, interview by Olivia Whittaker, Zoom, April 25, 2025.

[4] “Decoding Downwinders Syndrome: Effects of Radiation Exposure,” Downwinders, published September 9, 2023, Decoding Downwinders Syndrome: Effects of Radiation Exposure – National Cancer Benefits Center – Downwinders.

[5] Janet Burton Seegmiller, “Nuclear Testing and the Downwinders,” History to Go (Utah Division of State History), n.d., accessed May 2025, https://historytogo.utah.gov/downwinders/.

[6] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[7] “Dixon Says U.S. Can’t Risk Halt on Bomb Tests,” Milford News, November 1, 1956, in Utah Digital Newspapers, accessed May 2025, newspapers.lib.utah.edu.

[8] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[9] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[10] Iola Whittaker, interview by Olivia Whittaker, Zoom, April 12, 2025.

[11] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[12] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[13] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[14] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[15] Bruce R. McConkie, Mormon Doctrine (Bookcraft, 1958), 639, Mormon Doctrine : Bookcraft Inc : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

[16] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[17] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[18] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[19] Iola Whittaker, additional information over text message to Olivia Whittaker, April 25, 2025.

[20] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[21] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[22] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[23] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

Interviews

- Zoom call, Carlisle, PA, April 12, 2o25

- Zoom call, Carlisle, PA, April 25, 2025

Full Transcript from First Interview

O: Can you paint me a picture of the environment you grew up in? What was your town like? What was distinct about that time?

I: When I was young they were testing the atomic bomb over in Nevada, they would announce the time that they were going to test it. We could all go out and set on our porches, and when they dropped the bomb, there was what we would see is this huge white flash that it— like probably less than one second. And so we would all: “Okay, well, the bomb’s gone off!” you know, when we would go on our merry way. But because of that, what happened later and had developed. because we were setting out and the towns that were even further to the south like Saint George, Utah, it broke the windows in the stores, and the sad thing that happened— and they did not know it until it started to develop 20 and 25 years later— is all of the people that had cancer. And the very important program that started was called the “Down Winders”…Probably that one thing that was the bomb happening and the future of the US was probably one of the biggest major happenings, you know, in the 1950s. How did it affect my daily life? It really didn’t affect my daily life when it happened. We just went around and we kept, you know, playing outside doing whatever, even though some of the people in my town died of different cancers…we roller skated, we rode bikes, we attended my sisters a lot because that was another very Mormon sort of thing in families.

O: So it was a very Mormon area, right? Like it was very religious community?

I: It was primarily Mormon. However, because it was a railroad town, people came a lot from St. Louis and Chicago. So our town, interestingly enough, was kind of different than the majority of Mormon towns or towns, I should say towns in general, because even though the Mormon church was the dominant church, we had a Catholic church that was very active and through the years the Methodist Church was very active and then there were other churches that kind of would come and go, you know, because of the population.

O: So it was pretty religious?

I: Yep. They set the religious code. Yeah. When you went to church, you didn’t wear slacks. That even held over into the 60s that there was a dress code for people in college and high school. Like we could only in the later years say about the time I was 15…let the girls wear pants on Friday to school. Otherwise, it was skirts, you know. And we had those big flowing skirts with the huge, you know, the petticoats where we have to kind of sit in a desk and tuck our dresses under. That was that was kind of how we dressed to high school.

O: Okay, so, since we’re mainly talking about being a young woman in the in the 1950s or growing up as a woman in the 1950s…for the next question, when you were young, did you have dreams for your life that were different from what was expected of you as girl?

I: I’m sorry to tell you: the answer is no. We, you know, we were kids outside playing in those early years. Never thought about the difference between the men and women. You know, some of my best friends were the boys that I had grown up with … we never worried about it. Never thought about it in those early, early years. It was not until about 1955 that it even started kind of crossing my mind that as girls, we started to question, you know: “well, how come at school we can’t do track?” You know, “how come at school we have to take home-ec?” you know, so that was our first questioning.

O: When you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grew up?

I: You know, I don’t really think that I thought too much about what I wanted to be when I grew up until I got older. And the one thing I knew is I didn’t want to teach. I didn’t want to just teach. I didn’t just want to be a secretary. I wanted to go to college. And beyond that, I really hadn’t been exposed to a lot of things, even though when I was 12, my dad took us to Florida. And I was shocked when I found out my cousins still talked about the Yankees. I just did not know that. One big thing that did happen on that trip, though, is there had been a lot of trials and the name Rosenbergs. They were accused of giving the atomic bomb information to the communists. We were in a restaurant. I think I told you this. We were in a restaurant. Everything was dead silence. They put it on the radio. The electric chair execution. And I don’t know if it was both of them or just the one. That was a really big major thing that would have been in 1952.

O: Because you mentioned that you knew you wanted to go to college: what made you want to go to college? Where did that interest come from?

I: Well, I think, like I said, just the fact that, you know, I didn’t want to just go sit at a desk and take stenography. I learned it in high school, but it had no appeal for me to do that. And my dad was encouraging me to do that because he was of that old white men knew better sort of thing. And so if you wanted to have a woman have employment, they were either teachers, nurses, or stenographers. Nobody ever said, look, if you go to college, you could go into research or if you went to college, you could do this. And so until I was basically 17, 18 when I started college, I knew what I did not want to do.

O: Which was like a desk job?

I: A desk job; I didn’t want to be a nurse; I would not have made a good teacher. I’m pretty sure I would not have made a good teacher. And I hated home-ec.

O: You hated home-ec? You’re good at it.

I: You know, um like they made us wear, you know, because they saw women like this, what they made us do is make aprons. You know, well, I never wore an apron. My mother always wore aprons, but they tried to teach us how to cook. I had no idea what they were talking about, and when they said, okay, now, cream your creamier eggs and sugar, I just went to the refrigerator and got cream and poured it in there, and my teacher was like: “God, Iola! You don’t know how cream sugar and eggs?” I’d never heard about it before. you know That was not in the lexicon of my mother. “Put the cream and sugar together now whip this up for me.” I didn’t know what was called creaming. But no, I did not care for all that.

O: Huh. That’s funny to me because I feel like those are things that you’re good at.

I: You know, I’m really glad I learned some of it and yes, I have put it I put it to use, I think, in another way. I really enjoyed, you know, like you have such good art, and we had like a teacher, which I don’t even know who it was, It was probably a phys-ed teacher or something, gave us the basics of art, like “your head is shaped like an egg and your eyes are right in the middle.” You know, that’s pretty much the art. And then when we did live, we painted a plant. We drew a plant. That was the type of art we had. However, the morning church was always very, very active in the fields of music and drama and, you know, stage and everything like that. So I always was in band. I played a couple different instruments. We had choruses. That was that as far as music and that went. The schools all had active people in in those fields. And like I said, gym started out in the eighth grade, you had to take gym of some kind. And finally, by about the time I was 12, and 13, they let us start playing what we call kickball, which is basically a soccer. And then when we were 15, I remember …a new gym teacher, you know, “what would you like to do?” and [we] said: “Well, how come we can’t run track?” …it was big if they would let us go out and play softball. That was really big.

O: So in high school, What kind of things did they let you do in gym versus the guys?

I: Well, as I said, they when I was 13, they let us play kickball out on the end of the football field. We started to play, you know, some softball, which is what you kids got to do when you were little, you know, in your mini leagues. That was about the end of it. We didn’t have a swimming pool.

O: But they let the guys do more sports?

I: Oh yeah, yeah. You know, football was a very big, basketball was very big, track for the guys, uh, you know, then at that, I guess later on I didn’t pay that much attention. But after football, it was basketball and then field. In a small school, you know, almost all the guys participated.

O: If you said, like, “why can’t do play track?” or something, what was sort of the justification that was given to you?

I: The ladies that came as teachers, I would assume that because in college, they had to at by that point, they had to have a four-year college teaching degree. So I’m just thinking those ladies were probably never taught to teach anything on those few simple things for girls.

O: So did you have to have female gym teachers for the girls?

I: Yes, we did.

O: So it’s you think it’s that they couldn’t have those sports for girls because those women weren’t taught those sports?

I: Right. I think that that had to be the reason because they were not women that had been taught to teach girls field events. You know, it had never crossed their mind that, you know, we could run and play tag or something like that, but we had done that since we were five and six years old, but there was no track and field for women, and because we didn’t have swimming pool, it was not even thought about.

O: Did you did that make things like PE less fun for you, do you think?

I: Well, we thought it was fun. At least we could be outside and having a good time. You know, but with the school, it was always listed as gym and health, and you had to take class in gym and health. That was the requirement. The health, as I remember, was always caught by the football coach because well, the football coach coached everything. You know, he was he was a coach for everything. And believe me, you did not learn very much in health, especially you never learned anything about women health.

O: So you didn’t learn about like, you didn’t learn about like periods or you didn’t get like sex education.

I: Nothing! Word couldn’t even be mentioned! If you if you had a mother that didn’t teach you something— and my mother didn’t teach me until I started questioning her— It was not an open subject.

O: Do you think that was because of the more religious culture or do you think it was kind of like that everywhere?

I: I think in Utah, it probably was like that. um you know, our mothers probably grew up like that. Our aunts grew up like that. The teenagers older than me grew up like that, but that, you know, very, very protected, you know, that it was very hard for my mother to explain sex to me. And I knew nothing about gay people until I was a sophomore and the friends in speech class started talking about this one fellow. I had no idea what they were talking about. I did not know “gay,” but after I learned what it was, then I could connect it to some situations like friends of my Aunt Ada in California. And Ada kind of tried to tell me these older women were gay. And when they told me that there was an actor that was a heartthrob called Rock Hudson, when my aunt Ada told me he was gay, I was like: “Oh Aunt Ada, you can’t say that!” You know, but that that was my first, you know, beyond gay, I knew nothing.

O: Interesting. So do you think it was very much…the sort of thing to teach girls if there even was any conversations about sex and that kind of thing was abstinence or like “wait until marriage” type thing?

I: Yeah, abstinence was like pretty much the first sentence of any speech, you know, absence, yeah. It just, you know, it was just never talked about, you know, right And even, you know, even between our the girlfriends, we never talked about things like that.

O: Do you think that it was a more open subject for boys or do you think it was equally as avoided with boys?

I: I think if it was subject with boys, it was just because boys were trying to show off.

O: Right. Going back to my questions… were things like marriage and children presented to you as kind of inevitable milestones for your life? Like these were just things that you were going to do someday?

I: As far as, um, I’m pretty sure as far as my mother and father thought about what my future would be. And at one point because I was falling in love with your Papa, I think that that became a possibility, you know, I didn’t think about it very much, but yeah, especially in a Mormon community because they really stressed marriage and family and everything. And some of my friends— I had one friend who lived in her house, married, had children. Her father was there. She lived in the same house for sixty-some years because her father would not after high school, he would not let her move away or go to college. Nothing.

O: Wow. Was that…how common was that?

I: That I think that that was uncommon because by 1955 women were going to college. And a lot of women— and the Mormon church actually, again, they were a big influence because the Mormon church was very big on education.

O: So, what did it mean to you to be a woman in the 1950s? Like, were there role models of kind of the womanhood that you aspired to?

I: Well, uh, because it was a small town, we really didn’t have a lot of role models. You know, there were some women that were a little bit more independent. But as far, you know, like I had a dance teacher that was quite young, but she received polio—which by the way polio was another big thing that that was earlier.— um, my piano teacher was a woman. My dance teacher, though, was a man for all those years. And, you know, I went to like a mock United Nations and um Mrs. Roosevelt, She was somebody that you knew a lot about, but we didn’t really know about women that were scientists or doctors. There was…the women nurses, but, no, we didn’t have a lot of people that we could think about to compare ourselves if there was anything we wanted to do.

O: So were there like female celebrities that you were aware of? Like were there female celebrities that people looked up to?

I: Oh, yes, yeah. Movies were very big. I never pictured myself in anything like that, but I had a friend who said: “When I grow up, I want to go back to California and be a singer and dancer.” a lot of my friends like to buy the movie magazines. I was never totally engrossed in celebrity things like that. I obviously, you know, Elizabeth Taylor, Doris Day. Those movies were just really fun to watch, but they were not anyone that was an iconic person to me that I wanted to emulate.

O: When you were like a teenager, were you aware of women’s rights or women’s liberations movements? And if you were, what did what did you think of them?

I: No, the liberation of, you know, the feminine revolution started in the late 50s, but it started mostly in the bigger cities, which we were, you know, young, just trying to, you know, get through college, through maybe new marriages and everything. So when we talked about the feminist movement, in Utah, we were not involved in it…maybe somebody Salt Lake, there might have been something, but, you know, we were in college, so that was not an issue. And probably heard about it and never really paid that much attention to it uh through the 50s. It it was not a movement in Utah other than maybe if I’d known somebody in Salt Lake and that didn’t happen because Salt Lake was even more Mormon than I was. So yeah, the liberation movement [was] probably pretty much New York, LA, Boston, maybe Washington, DC.

O: When did you become aware or did you think that women were underprivileged compared to men? or did you know … any women that like weren’t comfortable with what was expected out of them in in being like a woman in in that role? Or like did any of your sisters struggle with that or anything like that?

I: No, not even in my sisters. I was, you know, several years older than my sisters, but I go back and I think there were like two women that were married at my age who left their husbands and I don’t know why or anything. There was one incident, however, when that was in graduate school. But see, that’s the 60s. That’s not the 50s. So no, in during the 50s, I don’t recall anything like that. I know that in my small town, I didn’t know at the time, but I learned that there were women in my town that were abused by husbands, and nobody said anything. Other men knew it, maybe if they had close friends they’ may have known it. There was a girl that was younger than me that we thought gosh, she’d have bruises on her, never, never even thought about that her father was an abuser and he was but nobody turned him in. There was one other incident when I was very young: we would have a weekend kids movies. My mother said to me: “Now, Iola, if Mr. Ferguson says ‘come on up and I have a good seat here, you can sit on my lap so you can see.” She said, “you just say no, thank you.” I never even joined the two things until I got older. Your mother didn’t tell you why. Maybe like six to ten years old. You just knew you didn’t do it.

O: That’s really scary that your parents would even let you around that person.

I: They had their children in jeopardy…!

[call cut off]

O: We were just talking about how it was very like concealed that there were men in the town that were abusive, and it was it was kept quiet.

I: Yeah so we didn’t we really didn’t know… the liberation movement. I’d say right until, say, 1957, I was 17, and then I started to put two and two together. And that’s when I started questioning, and I would say to my father: “How dare you men not… do something about this???” But at that time I was maybe 16, because sometimes my dad would have these conversations, which, of course, he would get angry and say, “Well, this is just the way the world is.” you know, but I never thought of it in terms of me being under privileged, but certainly there were, you know, after I started putting the two and two together, I obviously knew there were women that were—I don’t think that we use the word underprivileged— but we knew that they were in vulnerable positions that were out of their control to a point.

O: Right. Was it that they weren’t really allowed to get divorced?

I: These women that were they were allowed to get divorced, but they never, you know, they didn’t want anybody to know what was happening to them… it was it was frowned upon. They kept it very quiet and their children, you know, of course, their children could never say anything. I’m sure if they had said anything… and I don’t think I don’t think even teachers would say anything.

O: Why do you think that is?

I: I think it was either that it was such a closed society in a small town that there was really no one to turn to. I’m assuming that they would assume they would become the town gossip, and then the men would just abuse them more. I don’t know, you know, I obviously… women fell out of control. I will tell you— it happened later— but again, never putting two or two together, we had a teacher that was married to Mary and she was always more… not really boyish, but she wasn’t real feminine. And we never thought about it. And we went on a trip with the cheer team and everything to the state basketball game, and she was our… um what would you call it?…She was the adult that, you know, stayed in the rooms with the girls. after I left home about two years later, there was evidently a lady that came to Milford again, a gym teacher, and Mary left with her! And the town was just you know, the gossip was just unbelievable! But she finally took charge of herself and left, you know, to begin a life that she had probably always wanted, but a lot of gay people would marry just, you know, to cover it up. A cousin of mine did that. So anyway, it was just a closed society.

O: Do you think the man… did he know? Was he also gay or did he just think… that was just his wife?

I: I don’t think he knew. I really don’t think he knew. You know, they had two sons that were younger than me, but I don’t I don’t know. How do you know in a family? You know, things go on in a family you just don’t know.

O: If you had wanted to break the mold more, if you wanted to do something really different, would you have had a support system? Like, would there have been people in your family or people that you knew who would have supported you?

I: I think with uh I think with a lot of discussion, my dad would have ended up supporting me. You know, if I had said, look, you know, I want to, I don’t know, join the foreign service, or something like that. I think dad probably would have supported me and my mother would just say [no], you know, because she was raised in this small town… At least my dad had traveled a little bit, being from Florida and being in the what was called the Conservations… something. He had traveled. Dad knew a lot of things, but raising three girls, he was absolutely okay with keeping us very, very, you know, just very protected. Probably because of what he knew in his travel. But yeah, I think eventually he would have. My sisters really didn’t have much of a different time… I think my dad was a little bit easier on my sisters, you know, because they had already gone through me. But their experience was pretty much the same thing.

O: How did you convince him to let you go to college?

I: I just said… I went up and I went up to Salt Lake. I looked at the school. You know, I did that, but I said, “I just do not want to do that [secretarial work]”. You know, and he probably took a deep breath. He was probably talking to my mom who would talk to her sister that was in the town that had the college and they convinced dad that, okay, you know, she can do this. And he got me signed up for college, but interestingly, I called home after about a month because all of a sudden I realized, okay, I’m never going to be home again. This is it. I’ve made the break. And I called dad and I said: “Dad, well, maybe I made a mistake. I’m not sure if I did choose the right thing.” And he said: “Iola, I’ll talk to you at Thanksgiving so do a good job. bye-bye.” At that point it was all in.

O: Yeah, I think that’s the experience people have still have in college to this day!

I: But there now I’m in college and that’s when I said, you know, even at the college, we still had the dress code and only on Fridays could women wear slacks to school to class.

O: In high school and in college too, did being a woman make it harder for you to achieve things that were important to you, like what you wanted to do in school or what you wanted to study or like any career that you might have wanted to have?

I: I don’t know that it made it harder. They just didn’t introduce any ideas. You know, they never said: “Okay, you’re doing well in algebra. Maybe you can pursue that. Maybe being a woman rather than going into nursing, you could go into biology or something.” There was never an introduction like that. But as I said, I think the teachers had never been taught to do that.

O: Do you think that it was kind of expected that, okay, you were a woman and you were in college, but you’re probably going to just be married and work and be at home at some point? You think that was expected of the women?

I: While we were in college, you know, and then Mack and I got married, it was right on 1960. So, you know, I had gone through a couple of years of college and was going to have a baby, so we’re going to get married. I felt like, you know, I wanted to support Papa because he was very, very bright and I didn’t want to mess up any of his college career. So in that respect, I felt I really wanted to be a helper. I wanted to be somebody that would not put any roadblocks into either one of us. So I, you know, I worked and we had babysitters that we had to take the kids too. There was not a lot of possibilities of any birth control. The one birth control they had I tried and I couldn’t take it because it made me so sick and they said, no, that’s dangerous. So there wasn’t the birth control… So [when] Mack graduated, He was offered a job. I said: “No, your professors have all encouraged you to go to school.” And so he went to, you know, he started graduate school and we he was doing great in graduate school and we knew that he was going to get a PhD and so we just, you know, we just hung in there. We just did what it took to get through because in those days there was not a family that was going to pay tuition, you know. We just we had to do it and we did it.

O: But do you think that when you were in college and you started college, what did people think that the female students were going to do? Like if they were in college, but they weren’t really being presented with these opportunities of different things they could do with their grades?

I: The professors started to talk to the women and talk about like to me, my econ professor, he said: “You know, Iola, there are opportunities that you can apply for to do like an internship in the summertime.” Again, there was no financial backing, you know, to do something like that. And a lot of the women started to not just getting practical nurse, which was like two years. More women were getting RN’s. In fact Papa I think taught some of them and they were undergraduate, he’s now a graduate student. But there was one woman—but again, that’s 1960— but she broke the mold. She was the one that said “I don’t want to have a child, I do not want to have a husband.” And so I’m sure had I known more people and been in a different strata maybe of society or something I would have known more of these women. But yeah, women were starting to break the mold and say: “I want to do this,” you know, “this is going to be my goal and if I’m married, you go along with me.” or that’s when some of the girls started walking out of marriages.

O: How were those women treated? What did people in your sort of sphere think of them?

I: I remember thinking gosh that –I think her name was Arlene.— I thought she’s really brave to do this, you know, to just go out on her own. She found an apartment on her own and she was working, you know, at some type of job that she could pay that little bit of rent. And my thought was, yeah, she’s a pretty brave girl to take this on by herself.

O: Did you sort of feel like, I guess that it was expected of you to get married when you were in college and have that kind of that path and kind of be a housewife?

I: That was still the leftovers from the 1950s, you know, early 50s to mid-50s, it was just pretty much that was how your life was going to go. And that was a phase in your life that you were, you know, being a woman, married, happily married with children. That was, you know, what you were going to do. I of course, what I was going to do as I was working so that Mack got through school so that we would have a future. You know, I really have to say I think we worked together. You know, it wasn’t like, “oh gosh, Mack, I wish, you know, we were making more money” or things like that. That was not our prime target. So even though I wanted the marriage, I wanted the children, I knew what I was going to have to do, you know, to make a life for all of us. And it was okay at that point I was fine.

O: Do you think that if you were going to college, if you were that age, like nowadays, and there were different things that you could do, do you think that you would have rather spent some time working or having a career or do you think that you still would have wanted to like get married young and start a family young and focus on that?

I: I think I think if I was 18 right now, I think I would have really pursued the possibility of going into a job, you know, a little bit more than just a summer job, but going ahead and finishing college so that maybe I could work in the field, maybe of another country, you know, because I liked the studies, historical studies and everything. Mexico was very close and much safer then. So I could visualize right now that I would maybe like to go into like a foreign service or something because I love economics and I loved history…I thought I could do it all. That’s what I think.

O: So do you think, like when you say that, are there things that you didn’t get to do that that you wish you got to do at the time?

I: I don’t resent that I didn’t get to do them. I wish that I could have done it all, but I couldn’t because of how the how the world was set up, how the United States was set up, living my sheltered life, how it was set up. But as soon as we got through that phase, you know, and moved on, then I was always very active in community things. I was acting with the children. I would act with things that I wanted to do. And so I would feel fulfilled in my life with things like that. And then when I had the opportunity to go into business and everything, again, I had the support and so I went into business and I worked for a lot of years, you know, having my own business and having a partnership with some other women for a while and then having my own business.

O: Right. When did you start having your own business? What was that?

I: It was about 1967. It may be ‘68 because Jill was older then, and you know she was busy, your dad was busy, he was already, you know, he was now in college and busy and Shaun was starting in college. So now I had time. I had played a lot of tennis and everything while they were growing up and working in community organizations and volunteering, you know, for all kinds of things, taking on projects in the different clubs. So now I was ready, you know, to do something for myself. A higher education would have been great. And one of the things that I did when Mack got out of school, I started taking classes at an ET it was called East Tennessee State University. And so I, you know, then I went back to college and I enjoyed it very much. But I never, you know, attempted to get enough to do a complete BAA diploma, but I did go back to college. And I was very active in the two clubs there that were very much volunteer clubs that you had to take on, you know, some pretty good projects in the community. Sure. At that time I learned a little bit more and realized what was going on. There were a lot of women in East Tennessee that were very underprivileged, very much so.

O: When did you become more aware of like the feminist movement in the US and that kind of thing?

I: The feminist movement became—Steinem you’ve probably heard of Steinem— they, you know, now that television was putting stuff like that on, women were starting to feel like, “Hey, I can do anything.” So by say 1965 to 67, you know, I kind of started thinking about it and everything and then, the women really are big in the 70s. But by that time I’m 30…And I’m sure a lot of them in the big cities who were really trying to break into things, you know, they found it much harder.

O: When you became aware of the feminist movement, did you support it or were you confused or how did you feel about it?

I: You know, it’s not so much that I supported it, but I didn’t back away from any conversation about it or if there was an opportunity to participate in something, I never felt like I couldn’t. You know, there were things that popped up that kind of like, for instance, um the ski club, Snow ski. The ski club was started by men. and I and another two gals said: “Well, why don’t we go to the ski club?” you know, they were kind of taken aback from that, you know, that was kind of a big surprise. [Some of] the men were younger, so they were understanding. They had wives that wanted to do stuff too. So, you just went ahead and did it, you know, but we weren’t in New York trying to break into a law firm, you know. So I don’t know about that.

O: Those type of women that were trying to do, like really kind of rebellious type things, did you respect those women? Were you kind of like, “well, why do you want to do that?”

I: No, it was like “Jeez, that’s really not fair!” You know, you would hear a little bit about it on the news and you think “Jeez that isn’t fair.” But you kind of went on your merry way doing your thing. It’s not like you joined a march or anything. I don’t even know if there were any marches or whatever. And I remember working at one of my volunteer jobs was at what it called it was an organization called Service League, and you had to perform, you know, you had to sign up for a service. And I remember signing up at the hospital for the pediatrics and you would see these women come in from the hills, what I call the hills in Tennessee and they were you know, they were like 25 years old and they looked like they were 50. You know, just it was just the saddest thing ever. And the next year I signed up for the women’s clinic. and I would see those same women coming back pregnant and now they’re 27 and they now look more than 50, you know. Again, and it wasn’t fair because we would say, look, there are things your husband could do. “Oh, I would never expect my husband…. You know… a vasectomy.” That was just— that was just a big no-no. And those women had to suffer through it because they didn’t have birth control and their husband wouldn’t. [The women] probably would have got knocked down on the floor if they said “I want you to use [protection] or else.” That would be my impression. So women in my situation at that point, obviously we’re using, you know, whatever needed to be done for birth control. But there were those stratas of society.

O: Now, just for my reference, what year were you born?

I: The year?…1940.

Selected Transcript from Second Interview

I: They really didn’t say anything. They just announced on the radios—probably a day or two before, in the paper—that on such and such a day, at such and such an hour, the atomic bomb would be tested.

O: How often was it tested, do you think?

I: I remember very well—I remember two or three very well—because we would go outside. Because we didn’t know that the wind could carry this radiation around. So we’d sit on the front porch and look at the clock—“Okay,” you know—and then all of a sudden there would just be absolute white-out in the atmosphere, and you knew the bomb had hit.

…

O: So we can talk about, um, I’ll go back to that a little bit more and Aunt Ada and stuff later, but I want to talk about the bomb tests. So the bomb tests were in Nevada, right? So you were like a couple hundred miles away or something?

I: Yeah. Tops.

O: Tops, because you were in Milford, right?

I: Yeah, yeah, we were in Milford. And, you know, of course when they set off the bomb in Japan, uh, you know—years went by, the government really didn’t know exactly what they had, I think. But they knew that the people that had been working with it started to get radiation poisoning.

They did not really advertise that so much. And so when they told us that the bomb was going to happen, they probably should have told us, “Stay inside,” you know, “stay out of the atmosphere maybe for twenty-four hours,” or something like that.

I think that’s what they probably should have said, because they did say that in the ’80s, when China was setting off the bomb.

But they gave us no indication that any of that—we would be harmed by it in any way. They just didn’t tell us what their research was showing. And in the meantime, people were starting to get sick.

…

O: Um, so did you—because this is sort of the time of, like, Red Scare and McCarthyism—were you or people in your town… was there kind of this sense of a fear of communism, like infiltrating America or being a threat to the U.S.?

I: Yes. There—I think older people, you know, kids kind of gloss it over. However, I do remember, um, I think it was Saturday mornings—you know, we had the radio, so it had to be someplace between ’50 and ’56. On the radio, there was a program, along with some other programs, I Was a Communist for the FBI, and that was, you know, that was one of the programs that we listened to on Saturday mornings. I assumed that my parents heard the program too, because we had one radio. But um, I think that adults were more conscious of it just because of what Eisenhower had said, you know—and Churchill—you just don’t want communism to now take over where the Nazis left off.

…

O: …there are some more general questions that I wanted to get out of the way first. So um hm did you well, how did the threat of bombing not bombs in the US, but from like Russia shape your everyday life? So like, I know you had drills in school and like bomb shelters and things like that. But was it something that you thought about or worried about?

I: When we talked about bomb shelters, that was just military bombs. The Soviet Union did not have the atomic bomb at that point. but just bombs in general is why they, you know, it was kind of it was it was one of those things a drill like you kids had probably when you were in a high school or junior high and everything, a fire drill.

And so we had, you know, maybe like a fire drill once a year or something, but we had a bomb drill, which was the very same thing. and it was military above me. And no, I didn’t worry a whole bunch of about. And not through the late 40s early any time in the 50s.

I do tell you one thing I do remember along the line with the uh the Communist threat because Eisenhower became the president and he said to Kennedy under no circumstance like calming as they get into the Western hemisphere, when Stalin died, I was probably 13 or 14 and he had been really bad. um and by that time they were, I’m pretty sure developing the bomb. But at that point I remember being in eighth grade and they had a picture of Stalin, “He has died”… and the only thought I had is: “Oh my God, could there be something worse coming?” and there wasn’t because then it was Nikita Khrushchev.

…

O: So did you have to have female gym teachers for the girls?

I: Yes, we did.

O: So it’s you think it’s that they couldn’t have those sports for girls because those women weren’t taught those sports?

I: Right. I think that that had to be the reason because they were not women that had been taught to teach girls field events. You know, it had never crossed their mind that, you know, we could run and play tag or something like that, but we had done that since we were five and six years old, but there was no track and field for women, and because we didn’t have swimming pool, it was not even thought about.

O: Did you did that make things like PE less fun for you, do you think?

I: Well, we thought it was fun. At least we could be outside and having a good time. You know, but with the school, it was always listed as gym and health, and you had to take class in gym and health. That was the requirement. The health, as I remember, was always taught by the football coach because well, the football coach coached everything. You know, he was he was a coach for everything. And believe me, you did not learn very much in health, especially you never learned anything about women health.

O: So you didn’t learn about like, you didn’t learn about like periods or you didn’t get sex education.

I: Nothing! Word couldn’t even be mentioned! If you if you had a mother that didn’t teach you something— and my mother didn’t teach me until I started questioning her— It was not an open subject.

O: Do you think that was because of the more religious culture or do you think it was kind of like that everywhere?

I: I think in Utah, it probably was like that. um you know, our mothers probably grew up like that. Our aunts grew up like that. The teenagers older than me grew up like that, but that, you know, very, very protected, you know, that it was very hard for my mother to explain sex to me. And I knew nothing about gay people until I was a sophomore and the friends in speech class started talking about this one fellow. I had no idea what they were talking about. I did not know “gay,” but after I learned what it was, then I could connect it to some situations like friends of my Aunt Ada in California. And Ada kind of tried to tell me these older women were gay. And when they told me that there was an actor that was a heartthrob called Rock Hudson, when my aunt Ada told me he was gay, I was like: “Oh Aunt Ada, you can’t say that!” You know, but that that was my first, you know, beyond gay, I knew nothing.

O: Interesting. So do you think it was very much…the sort of thing to teach girls if there even was any conversations about sex and that kind of thing was abstinence or like “wait until marriage” type thing?

I: Yeah, abstinence was like pretty much the first sentence of any speech, you know, absence, yeah. It just, you know, it was just never talked about, you know, right And even, you know, even between our the girlfriends, we never talked about things like that.

…

O: When did you become aware or did you think that women were underprivileged compared to men? or did you know … any women that like weren’t comfortable with what was expected out of them in in being like a woman in in that role? Or like did any of your sisters struggle with that or anything like that?

I: No, not even in my sisters. I was, you know, several years older than my sisters, but I go back and I think there were like two women that were married at my age who left their husbands and I don’t know why or anything. There was one incident, however, when that was in graduate school. But see, that’s the 60s. That’s not the 50s. So no, in during the 50s, I don’t recall anything like that. I know that in my small town, I didn’t know at the time, but I learned that there were women in my town that were abused by husbands, and nobody said anything. Other men knew it, maybe if they had close friends they’ may have known it. There was a girl that was younger than me that we thought gosh, she’d have bruises on her, never, never even thought about that her father was an abuser and he was but nobody turned him in. There was one other incident when I was very young: we would have a weekend kids movies. My mother said to me: “Now, Iola, if Mr. Ferguson says ‘come on up and I have a good seat here, you can sit on my lap so you can see.” She said, “you just say no, thank you.” I never even joined the two things until I got older. Your mother didn’t tell you why. Maybe like six to ten years old. You just knew you didn’t do it.

O: That’s really scary that your parents would even let you around that person.

I: They had their children in jeopardy…!

[Call cut off]

O: We were just talking about how it was very like concealed that there were men in the town that were abusive, and it was it was kept quiet.

I: Yeah so we didn’t we really didn’t know… the liberation movement. I’d say right until, say, 1957, I was 17, and then I started to put two and two together. And that’s when I started questioning, and I would say to my father: “How dare you men not… do something about this???” But at that time I was maybe 16, because sometimes my dad would have these conversations, which, of course, he would get angry and say, “Well, this is just the way the world is.” you know, but I never thought of it in terms of me being under privileged, but certainly there were, you know, after I started putting the two and two together, I obviously knew there were women that were—I don’t think that we use the word underprivileged— but we knew that they were in vulnerable positions that were out of their control to a point.

…

O: And so, you know, I know you didn’t really care much for the religious code and that kind of thing. Do you think that other people who were more into that and who were more religious or had more of that moral foundation? Do you think they, you know, were against it?

I: Yes. I think the ones who were steeped in their religion Mormon or Catholic, and those are and we didn’t know too much about ___, but yes, I think that they felt like it was a mortal sin that it could be corrected, and that people should work hard in having it corrected, but yes, they were very judgmental and had no empathy for it and considered it a it was a sin more than it was a a a medical or emotional thing. It was simply a sin. and that, you know, I mean, the sin of it was is that people acted so awful about it. And the Mormon church, and I think, you know, now the Catholic Church in their attitude but ___, you know, didn’t believe in it and shouldn’t practice it, but you couldn’t condemn them, and the Mormon church was still having seminars on how to redo them and the Mormon church I except for the people who have had any direct relationship and understand because maybe a child or a cousin or an aunt or an uncle, where they’ve actually seen it up close those that live out in law land still are just awful stupid not unformed.

…

O: So did your parents… your parents weren’t really Mormon or they didn’t really care about you being very, very much against it.

I: It was, you know, it was a topic of contention, especially in Milford, not in other towns as much as in Milford, because in Milford, we had the different religions. so many of us felt put upon by the rules that society had, and that the people, you know, things like if somebody would make a statement to my sister: “Well, gosh, you’re so nice, but you’re not a Mormon!” that’s that how narrow their thinking was. I went to college and I’m doing something and this woman who this young woman who was my age walked in to start college and I’m sewing or something and she said something about “Well you know every stitch that you take on a Sunday is like something putting the nails in Jesus” or something, you know.

And I said, what? You know, I mean, they made up stories like that that had that were just dumb. You know, just that’s all I know to say, you know, just had lived in such a cloistered like anything that they didn’t have as their activity was my goodness, you don’t go out and rob and steal and and have houses of ill repute, but my goodness, this is amazing cause you’re not a Mormon. oh, here’s a good one: You know how when kids are developing and their little foreheads, you know, the skull starts to form. It was a big thing in Utah about if those little if you could feel those little nodules on their skeleton, they were growing warm and morns, you know, and so people would check you, you know, you have a Mormon horn.

Further Research

- Elaine Tyler May. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York: Basic Books, 1988.

-

“Mrs. America: Women’s Roles in the 1950s.” American Experience. PBS. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-mrs-america-womens-roles-1950s/.

-

Jennifer Miller. “‘There’s Got to Be More out There’: White Working-Class Women, College, and the ‘Better Life,’ 1950–1985.” Journal of Social History 44, no. 3 (2011): 703–726. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27672810.

-

Jerry A. Jacobs “Gender Inequality and Higher Education.” Annual Review of Sociology 13 (1987): 153–185. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2083428.

Leave a Reply