By Aidan Keillor

“So Great was the pent-up demand for houses, cars, washing machines, sofas, radios, sinks, and myriad other items large and small that had been unpurchased during the depression and unpurchasable during the war.” (H.W. Brands, American Dreams, p. 70)

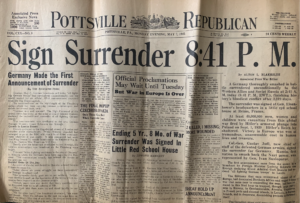

Newspaper from VE Day [Victory in Europe] from Saint Clair’s local newspaper, the Pottsville Republican (Bernard Grace)

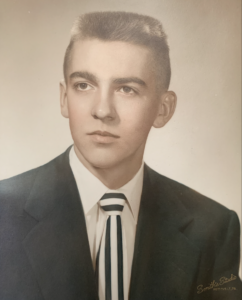

Bernard Grace was born in Saint Clair, Pennsylvania on July 10 of 1936. He would spend the first years of his childhood in the Great Depression and World War II. He would come into adolescence in the postwar period and be a teenager throughout the 1950s. He lived in Saint Clair, a small town that was created around its coal industry in the late 1800s, up until the coal industry would fail. He would live in St. Clair until he graduated from Pennsylvania State University, where he would move away in search of work.

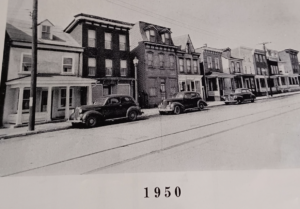

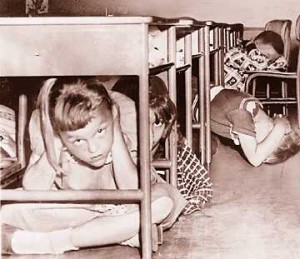

The 1950s was a time when the modern United States was starting to take shape. The introduction of the middle class shaped the country economically and the growth of the suburbs brought people from cities and rural towns to live in them. The introduction of the GI bill and the reintegration of veterans from the Second World War into civilian life brought a time of prouise. With the war over, it brought along an availability of goods that hadn’t been seen since before the war. Bernard Grace remarks, “After the war was over, it seemed like everything was available again and things like that. During the war years we had ration books, and when the war was over, all that stuff stopped. Now again the town I lived in; things seemed to be available for you.”[1] Bernard Grace would often recall this in comparison to the war. The war was rough on many Americans with all the sacrifices both home and abroad. The stark rationing of goods like food, rubber, and other goods was in great comparison to the availability of goods in the 1950s. In Brand’s American Dreams, he writes about the comparison of the availability of things in the war and after. Brands claimed, “So Great was the pent-up demand for houses, cars, washing machines, sofas, radios, sinks, and myriad other items large and small that had been unpurchased during the depression and unpurchasable during the war.”[2] The availability and abundance of goods was a wave of relief for all people, especially people in coal mining towns which had been hit hard by rations.

Bernard Grace also remembers the leisure life of the 1950s. With the United States having a strong economy and abundance of goods and free time, movie theaters and dance halls became very popular drawing teenagers and young adults to them. Bernard Grace recollects, “We would go to ice cream parlors and use their jukeboxes. When you were older, and you knew somebody that had a car we would go to this place called The Globe and it was a dance hall. We would take people on dates and take them to the movies. It was a great way to grow up.”[3] The 1950s brought in an astounding amount of recreational and leisure activities all over the country. In Nancy Hendricks’s Daily Life in 1950s America, the growth of recreational activities was very evident. Nancy Hendricks writes, “It could be argued that dance found its way into the daily lives of average Americans more than any other period in American history.”[4] It was also evident that the movie business was also booming in the 1950s showing the growth in leisure activities and recreation in the 1950s. Brands states, “Entertainment, in its numerous forms–grew into a powerhouse of its own. Hollywood churned out movies by the hundreds, with an increasing portion of them aimed at children and families.”[5] The extent of the growth of films and movie theaters was not just in suburbs and cities but had also made its way into St. Clair. The entertainer industry in all ways had grown due to the 1950s all over the county and was increasingly being geared towards family lifestyles.

Although there many fond aspects of the 1950s that Bernard Grace remembers, there were pitfalls that came with this era and some things in Bernard’s life in a small coal mining town did not change and seemed the same as compared to the suburbs and cities. H.W. Brands only covers the postwar period’s effect of the suburban but misses its effect on coal towns and how there was some change, yet not as much compared to other areas of the country. Brands often refers that both blue collar and white-collar families would be able to own expensive things and have a middle-class lifestyle. Brands notes, “In the 1950s factory workers and office workers alike earned enough money to support a thoroughly respectable middle-class lifestyle.”[6] This was not evident for Bernard Grace. With his father working for the railroad and his mother at home, his family would not be able to afford this lifestyle. Bernard Grace remembers, “For my dad, he worked on the railroad, he had a labor-type job. The most money he made in his life, in a year, was $1,200 ($12,000 in today’s money). A lot of people didn’t have a lot, but you didn’t really miss not having it because nobody did.”[7] Because of Bernard Grace’s family standings they would not be able to afford many of the newly affordable things of the 1950s like cars, telephones, and televisions. Bernard Grace also recalls, “Some families had cars, we (Bernard Grace’s family) never had a car, we never had a phone in our house. We used our neighbor’s phone for years. It depends where you were coming from. If you lived in the cities, I’m sure things were a lot different, but in a small coal-mining town, it was not.”[8] Brands does not classify this and focuses more on how much cheaper and available for regular people electronics and cars were for people. Brands claims, “Much of the economic activity revolved around the physical needs and wants of the Baby Boomers and their families.”[9] Brands only focuses on a broad scale that says that families were able to afford electronics and luxury items, yet not everyone was in this situation in the 1950s and in small coal towns like Bernard Grace’s. The 1950s did not change the lives of people to the extent of the suburbs and urban areas.

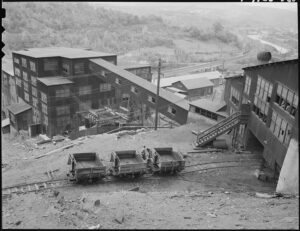

Along with the introduction of affordable technology for people, the 1950s and the end of World War II would bring in many technological innovations in the energy industry that were cleaner and less taxing on resources. One of these innovations was the development of nuclear energy after the Second World War. The development of this energy was in part with the development of the nuclear bomb and offered a clean source of energy to power the United States. According to Jay Lehr, “Nuclear power was commercially attractive because it offered the opportunity to generate power without the air pollution that accompanied the burning of fossil fuels.”[10] Brands does not disclose the importance of this development of energy and does not show how its developments affected other industries like coal. In Bernard Grace’s town the coal mining business was the backbone of the creation of St. Clair and was one of the driving economies of the town. Bernard Grace recollects, “In this town I lived in [St. Clair], the garment industry was a big thing and coal mining was big”[11] The industry was the reason for the development of the town in the late 1800s. This is supported by Anthony F.C. Wallace’s St. Clair- A Nineteenth-Century Coal Town’s Experience With a Disaster-Prone Industry. Wallace states, “Three main groups of businessmen were responsible for the development of St. Clair: the owners of the underground mineral rights (the “landowners”); the colliery operators who extracted and processed the coal; and the transportation companies.”[12] These important coal companies being the backbone of the town would lead to the decline of the town and its industries. This was due to the introduction of nuclear energy. Bernard Grace would remark, “Coal mining was starting to reduce in popularity at that time because of new energy sources [nuclear energy], so people got out of the mines and people started to move away. I know when I got out of college, I had to relocate because there was no work where I came from, so I ended up going to a city to work.”[13] The introduction of nuclear energy would put the town in a steady decline leading it to mass unemployment and a closure of the mines. This situation goes against Brand’s stereotype of the 1950s as being a prosperous time in the United States because of St. Clair’s dying industry and dying town.

With the 1950s often associated with change, there was a push for racial change that marked the beginnings of the civil rights movements in the 1950s. In Michael J. Klarman’s “Brown, Racial Change, and the Civil Rights Movement” in Virginia Law Review. Klarman stated, “In the years immediately following the war, desegregation as a Cold War imperative became standard for political fare.”[14] The growth of civil rights and the fight against segregation was a growing topic and many civil rights leaders rose in the 1950s seeking political reform. Jim Crow and segregation still plagued the country and were a topic of protest. Brands claims, “Blacks numbered some seventeen million in the mid-1950s, or about 10 percent of the population, and despite the migrations to the North during the two world wars, most still lived in the South, where the Jim Crow system of racial segregation remained.”[15] Brand’s association of racial change and Jim Crow to the 1950s and the postwar period was apparent but because of the smallness of St. Clair and the ruralness of the town, it seemed like race had never been a pressing issue, because of the little to no presence of African Americans. Bernard grace would remark, “Back in the 50s, in my town, there was one black family and there must have been 2500 people living there. There was never an issue with color because nobody was there so we didn’t have that situation.”[16] The small to no presence of African Americans in St. Clair would go against the association of the growth of civil rights and fight against segregation and the 1950s because there was no diversity in the town, he lived in. Bernard Grace was not exposed to these issues until later in his life because of the smallness of St. Clair.

The 1950s brought great changes to the United States and offer many opportunities for all Americans following the Second World War. The availability of goods in the United States and the introduction to family-oriented leisure activities would offer a good time to be alive. Race and the birth of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s would help institute civil change in the United States and new energy sources would create cleaner sources of energy. Bernard Grace’s experience in the 1950s brought him many opportunities and fond life experiences, yet it was not to the extent of others that lived in the suburbs and cities.

[1] Zoom Interview with Bernard Grace, April 13, 2022.

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 70.

[3] Zoom Interview with Bernard Grace, April 13, 2022.

[4] Nancy Hendricks, Daily Life in 1950s America (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2019) 176 [ProQuest].

[5] Brands, 73

[6] Brands, 80

[7] Zoom Interview with Bernard Grace, April 13, 2022.

[8] Zoom Interview with Bernard Grace, April 13, 2022.

[9] Brands, 71

[10] “Nuclear Energy: Past, Present and Future,” excerpted in Jay lehr, Energy and Environment (London: Sage Publications Inc., 2010) 97 [JSTOR].

[11] Zoom Interview with Bernard Grace, April 13, 2022.

[12] Anthony F.C. Wallace, St. Clair- A Nineteenth- Century Coal Town’s Experience with a Disaster-Prone Industry (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, inc.,1987), 54.

[13] Zoom Interview with Bernard Grace, April 13, 2022.

[14] “Brown, Racial Change, and the Civil Rights Movement” excerpted in Michael J. Klarman, Virginia Law Review (Charlottesville: Virginia Law Review, 1994), 27 [JSTOR].

[15] Brands, 84

[16] Zoom Interview with Bernard Grace, April 13, 2022.

Interview Subject

Bernard Grace, age 85, spent his childhood and adolescent years in Saint Clair, Pennsylvania, a small coal-mining town outside of Pottsville, Pennsylvania where he experienced the changes brought to the US during the 1950s until he attended Pennsylvania State University.

Interviews

– Recording Zoom Interview with Bernard Grace on April 13, 2022

– In-person interview with Bernard Grace on April 17, 2022

Selected Transcript

Q. How drastic was the change in the way of life after the Second World War?

A. “In the town that I came from, it didn’t seem like it was that different other than, during the war in the 40s, you couldn’t get things. After the war was over, it seemed like everything was available again and things like that. During the war years we had ration books, and when the war was over, all that stuff stopped. Now again the town I lived in, things seemed to be available for you.”

“You didn’t sorta notice the change. Things might have been a little different, but I graduated from high school, in this town I lived in, the garment industry was a big thing and coal mining was big”

Q. With the influx of better jobs/ pay, did your family go on vacations, did they get a car or have a television because they got paid more?

A. “For my dad, he worked on the railroad, he had a labor-type job. The most money he made in his life, in a year, was $1,200 ($12,000 in today’s money). A lot of people didn’t have a lot, but you didn’t really miss not having it because nobody did. Some families had cars, we (Bernard Grace’s family) never had a car, and we never had a phone in our house. We used our neighbor’s phone for years. It depends where you were coming from. If you lived in the cities, I’m sure things were a lot different, but in a small coal-mining town, It was not.”

“Coal mining was starting to reduce in popularity at that time because of new energy sources [nuclear energy], so people got out of the mines and people started to move away. I know when I got out of college, I had to relocate because there was no work where I came from, so I ended up going to a city to work.”

Q. How was leisure life in the 1950s? Was there more to do outside of work and school?

A. “After the war things were a lot better. Things were available. The 50s was a good time to be alive. Everything was available and there were a lot of things to do with a lot of fun involved. We would go to ice cream parlors and use their jukeboxes. When you were older and you knew somebody that had a car we would go to this place called The Globe and it was a dance hall. We would take people on dates and take them to the movies. It was a great way to grow up.”

“We would take people out on dates. In our crowd, we had a lot of that. Somebody would date someone one night, and then the next week somebody else would take them out. It wasn’t very serious but it was fun all the time. It was a great way to grow up and in this generation when we get together and talk, we talk about how good it was to grow up in that time. It’s gotta be tough today for people compared to back then.”

Q. Did you remember any racial issues either happening in your town, on the radio, or in the news?

A. “Back in the 50s, in my town, there was one black family and there must have been 2500 people living there. There was never an issue with color because nobody was there so we didn’t have that situation.”

Further Research

- Anthony F.C. Wallace, St. Clair- A Nineteenth- Century Coal Town’s Experience With a Disaster-Prone Industry (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, inc.,1987)

- Nancy Hendricks, Daily Life in 1950s America (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2019) [ProQuest]

- “Nuclear Energy: Past, Present and Future,” excerpted in Jay Lehr, Energy and Environment (London: Sage Publications Inc., 2010) [JSTOR]

- “Brown, Racial Change, and the Civil Rights Movement” excerpted in Michael J. Klarman, Virginia Law Review (Charlottesville: Virginia Law Review, 1994) [JSTOR]