By Sarah Cayouette-Gluckman

“You could be a feminist but not be like, progressive about being gay,”[1] recalls Dr. Susan Cayouette about life as a lesbian in the 1970s. Cayouette lived in Pittsburgh, attending graduate school at Duquesne University, in the mid-70s. It was easy for her to recall the homophobia she experienced in an otherwise progressive academic setting. “[My professor] had asked for these… journals, right, so I did my journal and, you know, in it [I] talked about, you know, being lesbian and he gave me like a C-minus or something,” she recalls, “[he] said, you know like, how dare you write about such trivia.”[2] Cayouette may have hoped that the burgeoning U.S. women’s movement would help to combat hostile attitudes like this. But despite the movement having spread across the country throughout the 60s and 70s, there were still many demographics of women that were being left behind by this second wave of feminism, including lesbians. H.W. Brands, in his book American Dreams: The United States Since 1945, describes second-wave feminism in the U.S. as a two-sided debate, feminists vs. anti-feminists, framed in the attempt to pass the Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution. Brands offers a moderately varied look at the anti-feminist side, separating out the religious right and their specific concerns from others suspicious of feminism, but his interpretation of the feminist side lacks such nuance, leaving out any mention of the conflicts that arose within the

Newspaper ad for the National Organization for Women in the Philadelphia Inquirer, 1967, courtesy of ProQuest

women’s movement and the complexity of the relationship between mainstream leaders and those with other marginalized identities.

The leading organization advocating for women’s rights in the 1960s and 70s was the National Organization for Women, or NOW. Created in 1966 and presided over by Betty Friedan as president, NOW was meant to act as an NAACP for women.[3] Brands describes NOW’s involvement in leading strikes and marches across the country, and in trying to get the Equal Rights Amendment ratified. While he adequately discusses the major efforts and achievements of NOW during the time period that he’s focused on, he leaves out any mention of the inner workings of the organization. This is where divisions among feminists can be seen, most notably the exclusion of lesbians from mainstream second-wave feminism and NOW.

Cayouette remembers explicitly not wanting to be involved in the Pittsburgh chapter of NOW because “[she] perceived it as not lesbian friendly.”[4] She doesn’t recall this issue being widely discussed or reported at the time, but the perception is backed by explicit homophobic behavior and the systemic expulsion of lesbians from NOW. Lesbians constituted a large portion of NOW’s early following, much to the dismay of then-President Betty Friedan.[5] She believed that lesbian issues and women’s issues needed to be kept separate in order to preserve the “political efficacy” of the women’s movement.[6] “The women’s movement was not about sex,” Friedan says in her memoir Life so Far, “but about equal opportunity in jobs and all the rest of it.”[7] She discusses in this same memoir how she was nervous about lesbians hijacking the movement from the inside out. Reports that “the lesbians were planning to take over leadership of the New York chapter of NOW”[8] sent Friedan into a tailspin and led to “purges” of lesbian leadership from NOW chapters across the country. Friedan describes this as “the responsible leaders of NOW [managing] to… diminish disruptions.”[9]

Christopher Street Liberation Day, June 20, 1971, courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections

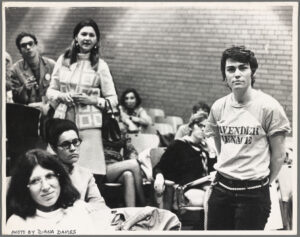

Shortly after this purge, many lesbian members of NOW and their supporters staged the Lavender Menace protest at the 1970 Congress to Unite Women in New York City.[10] Wearing purple shirts bearing the words “Lavender Menace,” a phrase used by Friedan to describe the lesbian problem, seventeen women “took over the auditorium”[11] and discussed for two hours the difficulties of being a lesbian in the heterosexual women’s movement.[12] They also demanded that NOW adopt a resolution to “accept lesbianism as an integral part of the women’s liberation movement.”[13]

One notable woman involved in organizing the Lavender Menace protest was Rita Mae Brown. A prominent leader in NOW, Brown was one of the many women affected by the purge when she was ousted from her position as an editor of the NOW newsletter in New York City. She would then go on to quit from her other NOW leadership positions and become involved in the founding of several lesbian-feminist organizations.[14] Similar instances would occur across the country and many local lesbian-feminist groups would continue to be formed. In a statement from Brown and two other lesbians who left NOW with her, the homophobia Cayouette perceived in NOW was spelled out; “enormous prejudice is directed against the lesbian [in NOW].”[15]

Rita Mae Brown at the Lavender Menace protest, courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections

While the lesbian community looked outward to create their own support in fighting for women’s equality, they never stopped pursuing equal representation within NOW. In 1971 at the NOW National Convention, a “pro-lesbian declaration,” drafted by members of Los Angeles’s Lesbians Feminists, L.A. NOW, and L.A. Daughters of Bilitis, was adopted.[16] This declaration led to the first official recognition of the “intolerable form of oppression”[17] lesbians faced at the hands of NOW, but still could not solve all of the problems they encountered. The resolution made it NOW’s official platform to support lesbianism “legally and morally” but did not change the fact that NOW would not spend time and resources on fighting lesbian specific issues.[18] The complex relationship between the lesbian community, as well as other marginalized communities, and NOW and mainstream second-wave feminism, would not be solved by one declaration and would continue in the following decades, eventually leading to a third wave American feminism centered around the intersectionality of these various identities.

The Atlanta Lesbian-Feminist Alliance walking in the ERA march, Washington DC, July 9, 1977, Courtesy of Southern Cultures Magazine

“It was okay for everybody else to, you know, get taken care of,”[19] recalled Cayouette about not only seeing the lack of representation in NOW, but watching women like herself being actively excluded. This very real struggle experienced by many, like Susan Cayouette, of feeling unwelcome in a movement they wanted to fight for that should have been fighting for them was not present in Brands’ interpretation of the women’s movement in the 1960s and 70s. He opts to leave out these chapters of complexity in favor of a simplistic battle between the feminists and anti-feminists. A survey of this period in history like American Dreams would not be complete without mention of the Equal Rights Amendment, Roe v. Wade, and the National Organization for Women but these were not the only important facets of second-wave feminism in America. As an author who otherwise does a good job of presenting the complexity of single sides of an issue, such as varying degrees of left-wing politics or different views within an administration on how to deal with foreign affairs, Brands does his readers a disservice by not including a mere few sentences on the vast lack of intersectionality within NOW and mainstream second-wave feminism.

The lesbian community and second-wave feminism had a long and complex relationship. Lesbians had to struggle through exclusion to make space for themselves and their unique issues in the fight for women’s equality in the 60s and 70s. Now, decades later, this story of overcoming exclusion is being left out of the mainstream retelling of the women’s movement. In a time with unprecedented amounts of documentation and historical evidence, it is the job of historians to uncover and teach these stories of exclusion like that of Susan Cayouette. In a survey of history like Brands’ American Dreams it may seem unimportant to tell these stories that did not affect everyone. However, when just a few sentences would change the reader’s perception of an entire social movement, they are essential.

[1] Video Interview with Susan Cayouette, Carlisle, PA, and Salem, MA, April 27, 2022.

[2] Ibid.

[3] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 176.

[4] Email Interview with Susan Cayouette, May 10, 2022.

[5] Friedan, Betty. “The Enemies Without and the Enemies Within.” Essay. In Life so Far, 221. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

[6] Gilmore, Stephanie, and Elizabeth Kaminski. “A Part and Apart: Lesbian and Straight Feminist Activists Negotiate Identity in a Second-Wave Organization.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 16, no. 1 (2007): 96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30114203.

[7] Friedan, 223.

[8] Friedan, 222.

[9] Friedan, 223.

[10] Gilmore, Stephanie, and Elizabeth Kaminski, 96.

[11] “Women’s liberation is a lesbian plot,” underground newspaper Rat, v. 3, #6, May 8-21, in Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975, Thirteenth Anniversary Edition, Alice Echols, (University of Minnesota Press, 2019), p. 215.

[12] Echols, Alice, and Ellen Willis. “Notes.” In Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975, Thirtieth Anniversary Edition, 215. University of Minnesota Press, 2019. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctvqmp26c.14.

[13] Kahn, Emily. “Lavender Menace Action at Second Congress to Unite Women.” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/lavender-menace-action-at-second-congress-to-unite-women/.

[14] Echols, Alice, and Ellen Willis, 213

[15] Rita Mae Brown quoted in Toby Marotta, The Politics of Homosexuality, (Boston Houghton Mifflin, 1981), in Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975, Thirteenth Anniversary Edition, Alice Echols, (University of Minnesota Press, 2019), p. 213.

[16] Pomerleau, Clark A. Empowering Members, “Not Overpowering Them: The National Organization for Women, Calls for Lesbian Inclusion, and California Influence, 1960s-1980s.” Journal of Homosexuality, #57, (2010), p. 848. https://dickinson.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/view/action/uresolver.do?operation=resolveService&package_service_id=6753049800005226&institutionId=5226&customerId=5225&VE=true.

[17] National Organization for Women’s National Conference resolution on lesbianism, 1971, in “Not Overpowering Them: The National Organization for Women, Calls for Lesbian Inclusion, and California Influence, 1960s-1980s.” Journal of Homosexuality, #57, (2010), p. 848-849.

[18] Pomerleau, 849.

[19] Video Interview with Susan Cayouette, Carlisle, PA, April 27, 2022.

Appendix

“Many women distrusted what they perceived as the elitism of NOW and other feminist organizations” (H.W. Brands, American Dreams, p. 177)

Interview Subject

Susan Cayouette, Ed.D, age 66, is a Co-Director for Emerge: Counseling and Education to Stop Domestic Violence in Malden Massachusetts. She attended her undergraduate institution, Stonehill College, from 1973-1977 and was a part of several demographics during this time that the women’s movement and second wave of feminism left behind. These include being Catholic, coming from a low-income and very tradition background, and being a member of the LGBTQ community.

Interview

Zoom call recording, Carlisle, PA and Salem, MA, April 27, 2022

Selected Transcript

Q. so in general you’d say that even though you were kind of, maybe like, surrounded by the ideas in a sense like the concept of like feminism with that name like attached to it… wasn’t something that you were really aware of until after you graduated college and like moved to a big city?

A. For some of them it was like a homophobic kind of response they were against. You could be feminist but not be like progressive about being gay you know homosexuality or whatever, however you want to call it you know and even though the women’s movement was started by a lot of women who were gay, lesbian, bisexual, the movement became primarily initially like a heterosexual movement and they didn’t wanna, they didn’t want to have like bad press because of homosexuality you know so they tried to like cut out the lesbians in the movement you know and that sort of became clear to me when I was at Duquesne.

Q. You kind of were alluding to this but would you say that like once you became more aware of like the feminist movement at large did you feel kind of ostracized as a lesbian compared to like the sort of like – who the target of the movement was?

A. If you think about it, even though women were trying to like be part of these movements they were being ostracized and if you think about that then think about being LGBT you know being gay or lesbian or bisexual and if you were a person of color that would probably be even worse.

Q. At what point in time do you remember there being a shift, or was there ever a time where you remember the women’s movement like taking a fore front and like was there ever a time where it was the most important thing, where there wasn’t some other politics on peoples mind that was more important?

A. I’m trying to think of when I actually felt that the, you know, the movement too include gay lesbian etc you know into the – into the – you know “we’re gonna do something about this”… seems like that was really late in the game you know I feel like that was – that’s been really really late so it was OK for everybody else to you know get taken care of.

A. Many of the original founding mothers of the domestic violence movement were lesbians and they also got iced out in terms of like being able to be visible because people were afraid they wouldn’t get funding from you know the federal government and that they wouldn’t get support for the domestic violence shelters etc.

Q. Do you know if domestic violence was something that was being talked about by the women’s movement in like the late 60s early 70s or did that come later?

A. The women were people who were doing [domestic violence counseling] like basically in their apartments and stuff and a lot of them were lesbian you know so they sort of started the movements you know and like anything else as it got chugging along they wanted more quote professional people and they wanted people with degrees you know and it became primarily like a white movement and you know primarily visibly a heterosexual movement… that was really disappointing to people, people were really disappointed by that.

A. It was pretty late in the game you know that it became not just a white woman movement, the domestic violence movement, and it also started to incorporate gay you know gay, lesbian, trans people in it too I mean we’re talking pretty late in the game like in the 90s in the first decade of the 2000s.

Q. So that description was about the domestic violence movement but would you say that kind of same thing was applicable to the women’s movement in general that it was very white, upper class, heterosexual, for a long time?

A. Yeah I mean I think there were… there were people in it… there were a few people in it who were not white and who were not heterosexual but they were you know told to be quiet I think, you know, and you know, don’t get people upset, that was sort of the, you know, message, you know, you can’t talk about that lesbian stuff because that really pisses people off you know that was the idea for a long time.

Further Research

- Nancy MacLean, The American Women’s Movement, 1945-2000 : a Brief History with Documents, (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2009) [book, Waidner-Spahr Library]

- Allison K. Lange, Picturing Political Power : Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020, Accessed April 29, 2022.) [ProQuest Ebook Central]

- Nancy A. Hewitt, 2010. No Permanent Waves : Recasting Histories of U.S. Feminism. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=321673&site=ehost-live&scope=site [EbscoHost]

- Martin B. Duberman, Left Out : the Politics of Exclusion : Essays, 1964-1999. (First edition. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1999.) [book, Waidner-Spahr Library]