By John Jankowski

On April 30th,1970, President Richard Nixon announced the invasion of Cambodia, an escalation of the Vietnam War. Just a few hours later, William F. [Bill] Causey assumed the office of student body president at American University in Washington D.C., and just three days after that, the Kent State shootings ignited college campuses. As Mr. Causey recalls, the U.S. invasion of Cambodia was “the striking of the match and Kent State was the lighting of the fuse.”[1]According to H.W. Brands in American Dreams: “The Cambodian invasion sparked the largest protests of the war.”[2]But it was two critical events, Kent State and the Cambodian invasion together, which caused the surge in campus protests, demanding a stop to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. In May 1970, the

general public was still divided on the Vietnam War, but the Kent State shootings and campus antiwar protests in reaction to it helped to shift public opinion toward the antiwar movement. Bill Causey witnessed it all; the nationwide protests which “changed a lot of minds” and revealed the truth about the Vietnam War, ultimately leading to greater political pressure to end the war.[3]

The Vietnam War had been escalating for many years when Richard Nixon ran for President in 1968. Public opinion against U.S. involvement in Vietnam was growing and Nixon promised in his 1968 presidential campaign that he would pull U.S. troops out of Vietnam and win a “just peace.”[4] During the first years of his presidency, the war in Vietnam seemed to be deescalating. An average of 46 U.S. servicemen were dying every day in 1968, with that average decreasing to just 17 servicemen a day in 1970, with fewer troops deployed.[5] Although support for the war was declining, there was still a great divide between those who supported the war and those who were against it. President Nixon’s description of antiwar protestors as “bums blowing up campuses” was directed to those who still supported the war effort.[6]

After President Nixon announced the invasion of Cambodia, campus protests mobilized.[7] The Kent State protests then erupted, and on May 4th, 1970, at 12:24 P.M., sixty-seven shots were fired by National Guard troops deployed on the campus, aimed at protesting students, killing four and injuring nine others.[8] As described by author Howard Means in “67 shots: Kent State and the end of American Innocence,” the shootings occurred “at one of the most turbulent crosscurrents in our national history.”[9] This was “the culmination of close to a decade of widening estrangement and open conflict between youth culture and established authority.”[10]

Bill Causey came to American University in September 1968 and immediately became very involved in politics; he was against the war and his antiwar views only intensified as the war continued. His growing activism caused him to run a successful campaign for president of the American University student body, which office he assumed on May 1st, 1970, for a one-year term.[11] He participated in the student protests on campus and witnessed the student unrest that gripped college campuses

nationwide so tightly. When asked if there were protests already on campus when he arrived, he answered, “not many at all but there were a few if you wanted to get involved in antiwar protesting in 1968.”[12]Implying that the worst of the protests were yet to come, Mr. Causey was the middleman between the students and the administration of the University when antiwar protests were most volatile. He quickly developed a connection with the American University President at the time, George Williams, and was widely supported by the student body which elected him. Mr. Causey, as part of the student leadership, as well as other protestors wanted one thing: the general public to wake up and see the terrible reality of the war being fought in Vietnam.

Historians Richard Peterson and John Bilorusky describe students of the May 1970 protests as “seeking to arouse seemingly unconcerned citizens to the wrongness of the American presence in Southeast Asia and to the dangers of the President’s Cambodia decision; and they were also trying to explain to generally bewildered and often hostile citizens what was happening on the campuses, and why.”[13] The cultural and political divide was seen in public reaction to the Kent State shootings which went from extreme outrage that university students had been shot while exercising their constitutional right to protest (some of the victims were not even protestors) to full-throated support of the National Guard’s actions.[14]

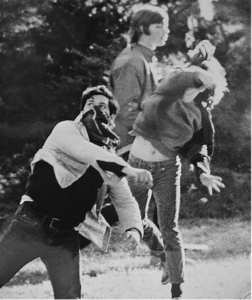

Mr. Causey discussed the May 1970 protests as first triggered by the Cambodian invasion as not “… just a student problem, it was countrywide, the country was very upset about Cambodia and that was the lighting of the match and then when Kent State happened things really blew up and because we realized that if you were going to have a serious protest against the war as a student, there was a risk you were gonna be shot and killed … like the four students at Kent State.”[15] Once the news circulated about Kent State, student protests exploded throughout the nation. Confirming Mr. Causey, a New York Times article published just days after the shootings stated, “more than 200 colleges and universities were closed in the spreading protest against the United States military involvement in Indochina and the fatal shooting of four Kent State University students by National Guardsmen.”[16] Mr. Causey also stated that the Kent State shootings “really polarized the campus at American University because we had police swarming all over the campus and they’re carrying guns, so … we thought, well, are we gonna be the next Kent State.”[17] With all of that fear came a lot of student resentment against the police entering their campus. Ward Circle, which runs through American University’s campus, was the site of many demonstrations, often peaceful (“honk for peace”) and involving the giving out of antiwar flyers, but sometimes, protests became disruptive and violent, including the blocking of traffic and hurling of rocks by students and with the police answering with teargas and arrests.[18] Mr. Causey recollects that “I go through Ward Circle, and I immediately think of those days in May of 1970 and what it was like … I remember when there were thousands of people there, the police were there, the sirens were going on, teargas going off, students getting arrested.”[19]

Four hundred of the nation’s universities were affected by strikes.[20] According to the student newspaper, “The Eagle” May 8th, 1970 edition, “approximately 50 percent of AU undergraduates are staying away from classes in support of the student strike.”[21] The strike was supported by American University’s faculty.[22] As student body president, Bill described his role during the protests: “I think he [George Williams] understood the role I had to play, I understood the role he had to play, he had to deal with parents and a conservative board of trustees and I had to deal with … 15,000 antiwar students so I think we understood each other and as a result of those constituents, we had to trust each other and I think we did and I think that made the relationship much better.”[23]

Mr. Causey noted that the student body was not completely unified against the war and that approximately 20% were more conservative politically: “by May of 1970, [it] was very hard to find a student that would defend the war in Vietnam, but they were more willing to defend Richard Nixon and the conservative movement and so there was some debate and division among students … I was debating the pros and cons of the protests and the war and up until Cambodia, you could find a lot of students who would engage in some very good discussions about the validity of the war.”[24] Mr. Causey views the Kent State shootings as greatly increasing student activism, he said “after the shootings, they became much more vocal, much more confrontational, a lot more students became involved in protesting. Students that would not normally get involved would sort of stand on the side

D.C. Police Chief Jeremy WIlson with a bullhorn on American University campus May 1970. Courtesy of Washington Area Spark

and kind of watch and making sure that they were far enough away that they wouldn’t get involved or hurt or injured. Now those students were actively involved and after Kent State happened, the students who were standing on the side and watching were the ones at Ward Circle, you know, vocally are protesting, so it really was a game-changer.”[25] Mr. Causey also describes the impact the Kent State shootings had on the students: “that famous photograph of the Kent State shooting with the student … lying … in the street … it was a confrontation between the police and the students and the students were the ones who didn’t have the guns, the police were the ones who had the guns and it was the students that were getting killed.”[26]

H.W. Brands states: “The Cambodian invasion sparked the largest protests of the war. On hundreds of campuses across the country, students boycotted classes and faculty suspended teaching in favor of discussions – which is to say, condemnation—of the war.”[27] This is partially true; the first sentence omits a reference to another very important event that ramped up these student protests: the Kent State shootings on May 4th, 1970. Brands also does not credit the protests for contributing to a change in public opinion of the war. When asked if he thought the protests made a difference, Mr. Causey thought they did and explained: “I think looking back on it after some time, I think we made a lot of our parents and a lot of adults in the country wake up and realize that the protest movement against the war was not a bad thing; that it might end the war. I think the Kent State shooting did more to galvanize public sentiment in the country than anything else … We were able to get some of the truth out and I think that did change the sentiment about the war and I think we put a lot of pressure on Nixon to get it over with much sooner than he would have otherwise.” [28]

All in all, the anti-Vietnam War protests had drastically intensified due to the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, coupled with the Kent State University shootings. American University students, like protestors of other campuses grieved the loss of life on campuses and in Vietnam, but also realized the importance of public opinion in bringing the Vietnam War to a close. The massive nationwide protests of May 1970 communicated to the American public that the war was wrong and why and the public (if it hadn’t already) began to listen. These events, as well as many others, supported a growing movement that eventually caused U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War to end.

[1] Zoom Video Call with William F. Causey, Washington D.C., April 22, 2022. [Causey interview]

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (Penguin Books, 2010), 170. Kent State is mentioned at the end of the same paragraph but not as a cause of the protests.

[3] Causey interview.

[4] Howard Means, 67 Shots: Kent State and the End of American Innocence (Da Capo Press, 2016), 7.

[5] Means, 2.

[6] Means, 7-8.

[7] Richard Peterson and John Bilorusky, May 1970: The Campus Aftermath of Cambodia and Kent State (The Carnegie Foundation, 1971), 5.

[8] Means, 78.

[9] Means, 210.

[10] Peterson and Bilorusky, 2.

[11] Causey interview.

[12] Causey interview.

[13] Peterson and Bilorusky, 16.

[14] Means, 87-89, 135-138.

[15] Causey interview.

[16] Robert D. McFadden, “Students Step Up Protests on War,” New York Times, May 9, 1970 [ProQuest]

[17] Causey interview.

[18] “The Eagle,” May 8, 1970, Vol. 44, No. 28 edition, sec. “Want Some Gas? CDUs Reaction to AU Honk-In.” http://digital.olivesoftware.com/olive/apa/wrlc/?href=AUE%2F1970%2F05%2F08&page=3&entityId=Ar00300#panel=document

[19] Causey interview.

[20] Robert D. McFadden, “Students Step Up Protests on War,” New York Times, May 9, 1970 [ProQuest]

[21] “The Eagle,” May 8, 1970, Vol. 44, No. 28 edition, sec. “Strike: Faculty Adapts and Supports.” http://digital.olivesoftware.com/olive/apa/wrlc/?href=AUE%2F1970%2F05%2F08&page=3&entityId=Ar00300#panel=document

[22] Ibid.

[23] Causey interview.

[24] Causey interview.

[25] Causey interview.

[26] Causey interview.

[27] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (Penguin Books, 2010), 170.

[28] Causey interview

Appendix

“The Cambodian invasion sparked the largest protests of the war. On hundreds of campuses across the country students boycotted classes and faculty suspended teaching in favor of discussions–which was to say, condemnation–of the war.” (H.W. Brands, American Dreams, p. 170)

Interview Subject

William F. Causey attended American University from 1968 to 1971, serving as President of Student Government from 1970 to 1971. After graduating, he attended the University of Maryland School of Law. Mr. Causey practiced law, primarily as a litigator, in Washington D.C. for several decades.

-Zoom Video Call with William F. Causey, Washington D.C., April 22, 2022.

“I am John Jankowski, the interviewer. I am interviewing William Causey via Zoom. The date is April 22nd, 2022. I am at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. William Causey is in Washington D.C. The topic of this interview is antiwar protests at American University during 1970-1971.”

[Mr. Causey provided a lengthy background summary.]

When did you attend American University?

“Alright, I was a transfer student and my first year at AU was in September of 1968. I transferred there as a sophomore. I went for my freshman year to Towson University in Baltimore, so I spent three years at American University, and I’m still connected to the university. I loved it and I had a great experience and I graduated in May of 1971.”

When did you serve as president of the student government of American University?

“My term started on May 1st of 1970, and it ended on May 1st, 1971.”

Were you involved in any activities on your campus?

“When I first came to AU, I got very involved in the young Democrats back in the 1960s. Young Democrats and Young Republicans were very active organizations, particularly on campuses. They also were very active statewide, so there would be a very active Young Democrats in Maryland. So, I got very involved right away in politics, and of course, when I started in the fall of 1968, it was right in the middle of the presidential campaign, so the Young Democrats on campus were very active, and very involved in the election we weren’t, when I say we I mean the young Democrats, there were about maybe 200 people involved in the Young Democrats on campus. …”

When you first came to AU, were there anti-war protests already on campus?

“Yes, there were a few, not many, not many at all. But there were a few, if you wanted to get involved in anti-war protesting in 1968, when I got to AU, you could find a group or two that would be doing that but they weren’t big, they weren’t well known, and within, as I’ve described, in the next year or so it really became the dominant movement on campus, but when I first got there, my first year was mostly devoted to traditional politics of you know a presidential election which was pretty tame compared to what happened in a year later with all the student protests around the country.”

What was your view on the Vietnam war?

I think I had very strong views against the war. I was a late bloomer. [My opinion] on the war didn’t really become firm until around 1967. So, the war had been going on for a couple of years it had been escalating. Johnson was really making a mess of Vietnam and by the time I got to college my freshman year, I was pretty antiwar. I thought the war was a mistake. I didn’t quite understand fully all of the implications of what was going on with the war until that first year. I started to read a lot more, talk to a lot more people, and I began to learn that it was basically a black war fought by blacks. Black young people, it was basically a white protest war, protested by white people ’cause black people were too busy trying to survive to be protesting. I began to have a better historical understanding of how we screwed up in Vietnam and then of course in 1969 one thing I forgot to mention, 1969 I think it was in 69 might have been 70 but I think 69 the Pentagon Papers were revealed and that told the whole horrible history of the war up to that point and everybody in the country realized that we had been lied to about the war and so I got radicalized you know my freshman and sophomore year and by the time all of these protests were occurring in 1970 I was very antiwar and very much against the war.”

How did the invasion of Cambodia affect the protests already on campus?

“Oh, that was the striking of the match and Kent State was the lighting of the fuse and once it was going off, that’s how I would describe it. So, it started with Cambodia and that wasn’t just a student problem, it was countrywide, the country was very upset about Cambodia and that was the lighting of the match and then when Kent State happened things really blew up and because we realized that if you were going to have a serious protest against the war as a student, there was a risk you were gonna be shot and killed you know like the four students at Kent State. So, that really polarized the campus at American University because we had police swarming all over the campus and they’re carrying guns, so you know we thought, well, are we gonna be the next Kent State. So, it was a pretty difficult time.”

The photos I’ve shared with you depict American University students taking part in a nationwide student strike against the Vietnam War. Did you take part in the strike and/or protests?

“Yes, I was at Ward Circle. I remember it vividly. Ward Circle is probably about a mile and a half from where I am right now, and every time I drive by American University, I’m still with the campus I still go to campus a fair amount, but every time I go to American University or I drive by it and I go through Ward Circle, I immediately think of those days in May of 1970 and what it was like. I can drive through Ward Circle now and it’s calm and it’s picturesque and they’re trees and grass and the campus is pretty and I remember when there were thousands of people there, the police were there, the sirens were going on, teargas going off, students getting arrested. I can’t drive through Ward Circle now without that thought going through my mind every time. So, it affected me a great deal and I was right there when it all happened.”

So you witnessed the brawls between the police officers and the students like in the photos on Ward Circle?

“Yes, I was on eyewitness.”

Did you communicate with the school administration about the protests?

“Oh yeah I was in constant, I mean, I think one of the advantages that I had as student body president was that I had a very good relationship with the administration not only the president and his top people but the faculty as well and I’m still in touch with some of the faculty members today 50 years later and I think the faculty trusts me they would ask me a lot of questions that they wouldn’t be willing to ask the more left-wing, pro protest students on campus ’cause they didn’t feel they would surely get an honest answer. But I was in constant communication with faculty and the administration and particularly George Williams [President of American University], because I mean he and I got along very well, I think we understood each other, I think he understood the role I had to play, I understood the role he had to play, he had to deal with parents and a conservative board of trustees and I had to deal with a, you know, 15,000 antiwar students so I think we understood each other and as a result of those constituents, we had to trust each other and I think we did and I think that made the relationship much better.”

When you look back at your time at AU now, do you think the protests and the strike made a difference?

“Yes, I do, I think looking back on it after some time, I think we made a lot of our parents and a lot of adults in the country wake up and realize that the protest movement against the war was not a bad thing; that it might help end the war. I think the Kent State shooting did more to galvanize public sentiment in the country than anything else and I know I talked to a lot of my friends who were students and I would ask them, what do your parents think of all this and they would either say they don’t really understand it or they’re very much opposed to maybe protesting and they don’t understand the student protest movement but I think over time, and I think that time period was fairly short I think within a year or so, a lot of people, a lot of adults in the United States began to realize how bad the war was, how much they had been lied to by the government over the war and began to see that the student protest movement was a positive thing. We were able to get some of the truth out and I think that did change the sentiment about the war and I think we put a lot of pressure on Nixon to get it over with much sooner than he would have otherwise. Of course, the other intervening event on that issue was Watergate which completely destroyed Nixon’s presidency, but I think the student protest movement made the made public officials realize that the public sentiment will no longer gonna be a war, it was gonna be antiwar and I did think it changed a lot of minds.”

Did you see a drastic change in the student protests after the Kent State University shootings?

Yeah, after the shooting they became much more vocal much more confrontational. A lot more students became involved in protesting, students that would not normally get involved who would sort of stand on the side and kind of watch and making sure that they were far enough away that they wouldn’t get involved or hurt or you know injured. Now, those students were actively involved and after Kent State happened the students who were standing on the side and watching were the ones at Ward Circle, you know, vocally are testing so it really was a game-changer.

What impact did the shooting have on students?

It was a shocking event in that all these protests are going on, on all these campuses around the country, but it was a shocking event because you had National Guard troops on a college campus firing live ammunition and killing four students and I’m sure you’ve seen that famous photograph of the Kent State shooting with the student lying, you know, in the street, I think that turned out to be the photo of the year. I think that that picture captured that moment. The horrible reality of that moment. So, that was, I mean, overnight there was a game-changer in the way people viewed these protests. Not only worry, now just vocally stating our objections, but it was a confrontation between the police and the students. The students were the ones who didn’t have the guns, the police were the ones who had the guns, and it was the students that were getting killed. So that was a big game-changer in the minds of a lot of students as to what was going on in the country.

Did any students oppose the protests?

We did have a block of students, as I said, my guess would have been it was about 20% of the student body were more conservative politically, a little bit more supportive of the war in Vietnam. Although it was very hard by May of 1970 it was very hard to find a student that would defend the war in Vietnam, but they were more willing to defend Richard Nixon and the conservative movement, and so there was some debate and division among students. I remember a lot of debates I had with students who were friends of mine on campus who were much more conservative about the war and about the protests than I was, debating the pros and cons of the protests and the war and up until Cambodia, you could find a lot of students who would engage [with] you in some very good discussions about the validity of the war or, you know, the impropriety of the war or the illegality of the war. But after Cambodia, it was hard to get students to get into that debate because most students became very anti-Vietnam. Now, I wouldn’t say they were pro protests, but they were anti-Vietnam and there was a divide there. I mean, you may have been opposed to the war in Vietnam, but it was stressful. Then to get to the active protest groups and there were a lot of students that were in that area in between that were against the war but didn’t want to get involved in protesting for whatever reason you know, but by large clear majority of students were willing now to take the next step and get much more involved.

Further Research

Michael T. Kaufman, “Campus Unrest Over War Spreads With Strike Calls,” New York Times, May 4, 1970 [ProQuest].

Robert D. McFadden, “Students Step Up Protests On War,” New York Times, May 9, 1970 [ProQuest].

Howard Means, 67 Shots, Kent State and the End of American Innocence (Philadelphia: Da Capo Press, 2016).

Washington Area Spark, “American University Strike: 1970”, Flickr.com. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://www.flickr.com/photos/washington_area_spark/albums/72157706590903731

“Strike: Faculty Adapts and Supports” American University: The Eagle, (Volume 44, No. 22), May 8, 1970. (And other articles from this issue of The Eagle). http://digital.olivesoftware.com/olive/apa/wrlc/?href=AUE%2F1970%2F05%2F08&page=3&entityId=Ar00300#panel=document

Richard E. Peterson and John A. Bilorusky, May 1970: The Campus Aftermath of Cambodia and Kent State (The Carnegie Foundation, 1971).