Driving down Vermont street

By Heidi Kim

Fires erupting, glass being broken, people running with items they have stolen from stores, police driving up and down the streets, civil unrest; the latter is what most use to describe the Los Angeles Riots of 1992. Judy Daley had been living in the neighborhood in which the riots erupted and recalls the “whole situation [feeling] surreal because I was in the car and everything is happening around me as if I was watching a movie.”[1] She remembers her disbelief in the actions of the civilians after news broke of the acquittal of four white officers. Daley recounts, “it was kind of scary because you know what’s good and bad and you see all the people stealing. So, you’re thinking, “My God, what is happening in the world?”[2] The LA Riots are an important event that is omitted from H.W. Brands’ book, American Dreams. Brand mentions and describes the Watts Riots of 1965, but omits any description of the LA Riots. The omission of the LA Riots and its outcome does not enlighten readers about the continued racial tensions and injustices that have occurred and continued to occur in the U.S. well after 1945.

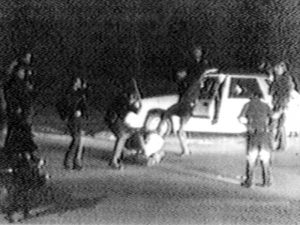

The LA Riots were a result of the acquittal of four white police men who severely beat a black motorist, Rodney King, during a routine arrest stop. Unbeknownst to the arresting officers, the arrest was recorded by local, George Holliday, who “sold [it] to a local television station, [which] subsequently broadcasted on television thousands of times.”[3] The video clip sparked national debate and produced many reactions. The police men responsible were indicted, but their trial was moved from Los Angeles to Simi Valley in the Ventura County, a “white, prosperous, suburban [neighborhood].”[4] Moving the trial gave an advantage to the police men awaiting their trial because the trial would now be held in a community that was predominantly white, upper-class citizens. By the end of the trial, while many were angry at the video, they were even more furious at the verdict. This erupted into angry crowds and mayhem; the riots lasted from April 29th – May 4th and resulted in “more than 50 people killed, more than 2,300 injured, thousands arrested, 1,100 buildings damaged, and total property damage [at] about $1 billion, [making] the riots one of the most-devastating civil disruptions in American history.”[5] Many extreme measures were taken because of the severity of the riots; these measures included shutting down public transportation, cancelling schools, and deploying the California National Guard. The LA Riots became another symbol for racial tensions that progressed and continue progress in urban cities.

As stated previously, the LA Riots resulted in looting of stores and physical violence amongst races. The LA Riots were also known as a “race riot” because of the tensions between different races. One of the focal points of the riots was the beating of Reginald Denny. Reginald Denny was a white truck driver who “was pulled from [his truck] by several black men, kicked and knocked to the asphalt, where one of the men smashed his skull.”[6] This, in addition to the looting and arson, contributed to the increasing tensions and disputes.

The LA Riots further intensified the racial tensions not only between blacks and whites, but among other races as well, in particular, Asian-Americans. Many Asian-owned business were targeted for looting and destruction. Historian Shelley Lee explains that the LA Riots represented a “shattered ‘American Dream’ and brought focus to their hold on economic mobility in a society fraught by social and ethnic tension.”[7] Many Asian-Americans looked forward to their hard-earned success with their businesses because Asian-Americans lie in the gray area between whites versus blacks. For Daley, being an Asian-American during these looting and arson incidents of Asian-owned businesses made her fearful because “what was happening on the streets, you don’t know if you’re going to be the next victim. You see that these people are looting already, then what is the next thing they are going to do?”[8] Asian-Americans were a significant part of the LA Riots and a part of racial tensions in history. Brands’ omission allows for readers to forget the racial tension between blacks and other races rather than just blacks and whites. The impact it had on Asian-Americans was a saddening thought to Daley because “these Asians worked hard to get their business up and running and they were being looted by these bad people.”[9] Driving down Vermont street (the main street leading into the Asian populated area of Los Angeles), many storefronts had shattered glass and broken structures. Daley recalls witnessing “a lot of people who were carrying appliances, like TVs, stereos and bags and carts of goods and foods; I saw them coming in and out of the stores.”[10] Tensions between the black community and the police had already erupted, so while the riots occurred police efforts were no match for the angry citizens. Many took advantage of the uprising and of “the ‘no police watching’ and [thinking] that they could take anything they want.”[11] Brands’ omission of the consequences of the LA Riots in his book does not reinforce that racial tensions are still high and very much alive even after previous events.

The rioting continued until May 4th, when “6,000 National Guardsmen and another 4,000 federal troops and Marines”[12] were deployed to ratify the incident. For most, many had started to resume their day-to-day activities towards the end of the riots. Public transportation that had been shut down was up and running again, children were going back to school, and adults were going back to work. For others who were spectators, like Daley, work did not really stop; “yeah, we still have to go to work. It’s not like the work is going to close. People are just talking about it [riots] at work; what they have seen, what has happened, what’s going on.”[13]

Daley’s account of her experience of the LA Riots offers a different perspective on racial tensions. While Brands does not discuss the LA Riots, Daley’s memories are able to give insight to the chaos that was a result of racial injustice.

[1] Phone Interview with Judy Daley, November 11, 2017.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Jacobs, Ronald N. Race, Media and the Crisis of Civil Society: From Watts to Rodney King. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed November 10, 2017).

[4] Reference List. 1992. “Days of rage.” U.S. News & World Report 112, 20. Readers’ Guide Full Text Mega (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOhost (accessed November 10, 2017).

[5] Wallenfeldt, Jeff. “Los Angeles Riots of 1992.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Last modified November 17, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/event/Los-Angeles-Riots-of-1992.

[6] Reference List. 1992. “Days of rage.” U.S. News & World Report 112, 20. Readers’ Guide Full Text Mega (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOhost (accessed November 10, 2017).

[7] Lee, Shelley Sang-Hee. “Asian Americans and the 1992 Los Angeles Riots/Uprising.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. Accessed November 11, 2017. http://americanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-15?rskey=jAFWiP&result=1

[8] Phone Interview with Judy Daley, November 11, 2017.

[9] Interview conducted by e-mail with Judy Daley, December 3, 2017.

[10] Phone interview with Judy Daley, November 11, 2017.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Staff, History.com. “Los Angeles Riots.” History.com. 2017. Accessed December 4, 2017. http://www.history.com/topics/the-los-angeles-riots

Phone Interview with Judy Daley 11.11.17

H: In your own experiences, what were the LA Riots of 1992?

J: Well, let’s put it this way: I was oblivious of what’s going on because I’m not really watching the news, but the day of, I had to pick up your uncle Dick at the airport at LAX and I drove downtown – not downtown – to LAX, not knowing that the riots were happening. So I was on the freeway on my way to pick up uncle Dick and your uncle Dick was saying, “how come at the airplane, when looking out the window, there’s a lot of fires?” And I said, “I don’t know.” So I picked him up, I drove him to his place, came back to LA, but there’s a lot of traffic already. The next day, when I went out, that’s when I see troubling sceneries. So, it was like watching a movie and I was driving. The people are more interested in looting the stores than hurting people.

H: Oh, okay.

J: So that’s why when I was driving at Vermont, between Beverly and 3rd street. So there’s a lot of people who were carrying appliances, like TVs, stereos and probably, uh, bags and carts of goods and foods. And I see them coming in and out of the stores, and I see all the stores on that street before, the glasses – the front glasses – are broken. So they’re just – for them it’s like having a party where they could just get everything. It was kind of scary because you know what’s good and bad and you see all the people stealing. So you’re thinking, “My God, what is happening in the world?”

H: So did you feel the need to call someone? Or you were just like, “This isn’t my problem”?

J: No, like I said, it was like watching a movie. I was like a spectator, I was just seeing all this happening in front of my eyes. So it’s not just like black people are stealing, it’s everybody: Asians, even those white people.

H: So how was it being an Asian-American during that time?

J: Well, it was kind of scary because what was happening on the streets, it’s like you don’t know if you’re going to be the next victim. You see that these people are looting already, then after what is the next thing they are going to do? It’s like they’re having a big party of something doing bad. So you don’t know what the next thing they’re going to do.

H: Do you remember watching all of this during the six-day period?

J: It was just like, um, during that week it was more on the vigilantes, because we still have to go to work.

H: Really?

J: Yeah, we still have to go to work. It’s not like the work is going to close. Because I was at the City of Commerce at the time, which is more industrial, so people are just talking about it at work; what they have seen, what has happened, what’s going on. So we feel secure when we’re at work, but then when you go to the street, especially in the streets with retail [stores]. You start to wonder, “Okay, are there they again? What’s the next move they’re [rioters] going to do?”

H: Did they ever try and aim for neighborhoods or did they stick to stores?

J: Where we live, they’re more [focused] on the stores.

H: Oh, okay.

J: So I think it was like people took advantage of the situation. The people who were looting during that time was taking advantage of this ‘no police watching’. That they could take anything they want.

H: Do you remember where you were when you, I guess, or when the news that the police men were acquitted of the Rodney King arrest?

J: I think it was Thursday/Friday. I’m not really sure, I might be at work.

H: So was that day kind of normal until you left work?

J: Until we went home. So it’s like, you know, after watch The Purge [movie], everybody stays inside. And all these people who wanted to do something bad are all on the street. So that was the part where we don’t really go out as much at night during that week. And then I think it was concentrated on some areas. It’s not like everybody just went berserk.

H: So when did you guys come to the U.S.? Around the sixties?

J: No, oh my God, you have to talk to your mom more often, haha. [We came here] in the eighties.

H: So you guys came in the eighties, what were your expectations of America and how did seeing the mayhem of the riots kind of changed that, if it changed at all?

J: Well, we were at Riverside, so which is more of a rural place. And then, ten years after – we came here in [nineteen] eighty-two and now it’s [nineteen] ninety-two, ten years – we have nothing to compare it except for what we know, which is that the United States is cold, weather wise. Okay? But other than that, it was like more of a fascination of what we see. We’re fascinated that they have all these freeways, we’re fascinated that people are driving. So it’s not like, how would you say it? It’s not like we would say that – I would say probably America was really rich. That everywhere you go, there is – its organized. Because in the Philippines it’s not that way; people are being resourceful, they do their own thing.

H: So you guys thinking that the U.S. is organized, it’s rich, and it’s well resourced, what was your guys’ initial reactions?

J: Oh, when the riot came?

H: Yeah.

J: Yeah, we were just saying, “Where did these people come from?” That people started beating each other, that there’s no remorse. Why are people being violent? Because we were not raised in a violent environment. And then you are seeing people, there’s so much hatred. So we were saying, “Where did this come from?”. Because in the Philippines, even though we had typhoons, we had all these monsoons, people tend to look at it – people tend to look at the brighter side.

H: And so seeing the LA Riots…

J: Seeing the LA Riot, we were just starting to say, “Why is there so much hatred? Why is it that you hate something and then suddenly they become violent with everybody else who’s not hurting you? Why are you taking their belongings that’s not yours?”

H: So prior to the actual riots, did you know of the case of Rodney King? Were you following the case?

J: Not closely, but it’s more of a what we call a “cooler” – “water cooler” discussion. It’s a “water cooler” conversation. Because before water bottles, when people wanted to get a drink of water in the office, there’s a water cooler, which is like what your Lola has at home. And then we just go there and get our water and then the people are going to say “oh did you hear? Oh did you know?” Things like that. And then people started discussing. And that’s how I know my news.

H: Is there anything else that you want to add?

J: Nothing I’ve already told you.

H: Okay, thank you!

Email Interview with Judy Daley

H: How did it feel being an Asian-American during this period of “white v. black”? Why did it you feel this way?

J: The whole situation felt surreal because I was in the car and everything is happening around me as if I was watching a movie. The people looting didn’t bother me at all. They were focused on getting as much as they can from the store.

H: How did it feel seeing Asian stores being looted and destroyed?

J: I felt bad because morally, what the they are doing was wrong. Felt disappointed to the looters because these Asians worked hard to get their business up and running and they were being looted by this bad people.

H: What was the difference in Asian-Americans rioting (if there were any) versus the Blacks rioting?

J: I think black rioting is more physical riots – hurting people of other races.

H: What were the reactions of other Asian-Americans during the riots?

J: Some Asians were indifferent because they don’t want to be involved. Very few Asians were involved with the protesting.