By Patti Kotrady

Marc Weinberg, a 67-year-old photographer and retired lawyer from Frederick, Maryland, played a significant role in the anti-war movement during the Vietnam War. From 1968 to 1970, Weinberg spent the last two years of his undergraduate college career at Ohio State University participating in campus protests. He recalls, “Whenever there was an opportunity to get involved, I would gather and make my voice heard. I didn’t believe in violence…We wanted to end the war.” [1] Particularly, Weinberg remembers a campus-wide protest during the spring of 1970 that gained momentum partially in response to the United States invasion of Cambodia. During the spring of 1970, in an attempt to attack North Vietnamese refugees, President Richard Nixon ordered an American occupation of Cambodia as well as the bombing of Laos. [2] According to H.W. Brands, “The Cambodian invasion sparked the largest protests of the war. On hundreds of campuses across the country students boycotted classes and faculty suspended teaching in favor of discussions—which was to say, condemnation—of the war.” [3] Although Weinberg’s narrative of protest certainly resonates with Brand’s description, his experience expands significantly on Brands’s terse explanation. Ohio State University’s 1970 protests were about more than just the Vietnam War—they also confronted larger issues of racism, student power, and police brutality.

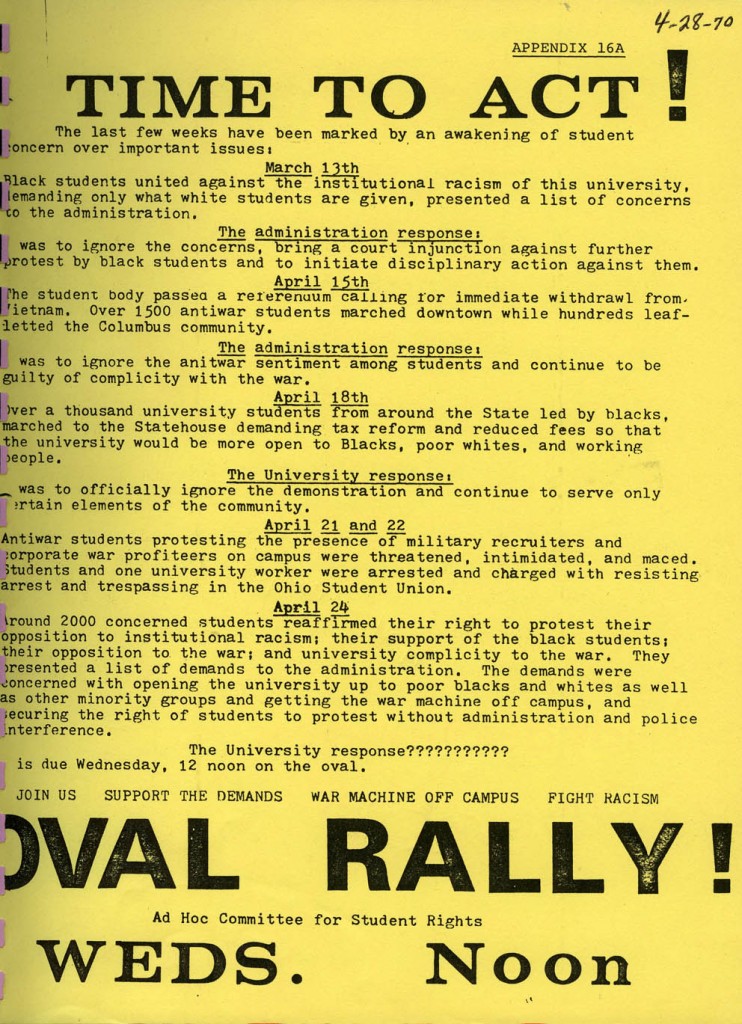

According to Brands, “Some Americans had objected to the war in Vietnam from the outset. They asked whether the status of a small country far away justified the expenditure of American blood and treasure.” [4] As a Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) student during his first two college years, Weinberg was not a part of the initial anti-war activism. He instead fit into what Rhodri Jeffrey-Jones categorizes as the third stage of campus protest from 1969 to 1972 in which students were “idealistic,” yet understanding of the importance of legislative politics. [5] By the late 1960s, students such as Weinberg became upset with the seemingly unjustified nature of violence in Vietnam and were willing to do all they could in order to end the war. In this effort, various groups on campus, including the Afro-American Society, the Women’s Liberation Front, the Anti-War Ad Hoc Committee, and the School of Social Work, submitted a series of demands to the Ohio State University Administration. [6] These demands included “that the University support the views of its students and condemn the continuation and expansion of the war in Southeast Asia,” “that ROTC courses not receive academic credit, and that ROTC instructors not have faculty status.” [7] In addition to these war-related demands, Ohio State students demanded “a degree-granting department in the field of ‘Afro-American Studies’ be established…,” “fees be lowered for all in-state and out-of-state students,” and “the establishment of a Planned Parenthood Center within the campus area.” [8] Yet, the administration refused to meet many of these demands. According to University Vice President James Robinson, “most demands have reflected only the concerns of self-appointed groups and have neither proposed nor suggested constructive programs that recognize what is already being done by the University to work toward our common objectives…” [9]

Students at Ohio State were not only concerned with issues regarding the Vietnam War, as Brands seems to suggest. They also advocated for racial inclusivity, women’s reproductive rights, and student liberties. Weinberg recalls, “We had a protest going for two things. One thing was a protest against racism on campus because black students on campus weren’t getting the same opportunities as white students were given, and the other thing was the war.” [10] Although Weinberg mentions that they had a “protest going for two things,” the student demands suggest that they advocated for rights of women and students as well. This can be further exemplified through a 1969 study by the Urban Research Corporation of Chicago. According to Jeffrey-Jones, researchers “surveyed 232 campuses and found that the draft was a major issue in less than 1 percent of protests. Whereas antimilitarism was a main issue in 25 percent of cases, two other issues counted for more: racial issues, at 59 percent, and student power, at 42 percent.” [11] Although Brands fails to mention African American, feminist, or student rights motivations for campus protests, these factors played a significant role in the activism of students at Ohio State University and other college campuses across the United States.

Ad-Hoc Committee of Ohio State University. “Time to Act!” Flyer, April 28, 1970. from the Ohio State University Library Archives

In addition to the Vietnam War, racism, and student rights, police brutality became a key concern of Ohio State students. When demands were not met, students fought back through both violent and non-violent protest. For example, Weinberg recalls a protest in April of 1970 in which students expressed their concerns: “To show that we believed in a closed campus, we decided that we would literally close the gates of the campus. And I was in that group, of course…the police came and said ‘Open those gates, dammit, or else.’ We didn’t open the gates, and they came busting through those gates, and that was the first time that I ever saw a police riot. They went ape…they were catching people and beating them over the head with their sticks. It was nasty and it was bad…From that moment on, that campus was in complete and absolute turmoil. [12] Due to the “turmoil,” administration put a dawn to dusk curfew on the campus [13]. Weinberg recalls, “I had no freedom…The police were running around in police cars with the police numbers taped black. They took off their badges and any identification. They had helicopters so if anybody gathered anywhere they dropped teargas from the helicopters.” [14] Historian Melvin Small further emphasizes the role of police on college campuses when he states, “during the academic year 1969-70, 7,200 young people were arrested on campuses.” [15] Weinberg’s story of police retaliation to student activism combined with Small’s statistic of general police involvement demonstrates the intensity and violence that arose from anti-war protests on college campuses.

In regards to police brutality on college campuses, Brands focuses on the shootings at Kent State. He writes, “At Kent State University in Ohio, protesters clashed with National Guard troops, who fired on the crowd and killed four students. Days later a similar tragedy occurred at Jackson State in Mississippi, where two students were killed by police fire.” [16] When the shootings at Kent State occurred, Weinberg and his peers were in the midst of a protest on their own campus. As news of the student deaths spread through the crowd, Weinberg remembers, “We were just shocked. They’re killing us. They’re killing us. It was very sobering. My friends and I, we were all gathered around and thought, ‘Is this the time to take up arms?’ I mean, it’s the army. How can you fight the army? You can’t do it…It felt like we were at war.” [17] As evident through Weinberg’s recollection, the shootings at Kent State represented a larger issue in which students and police forces were “at war” with one another. Weinberg even remembers that, when police forces charged the students, they shouted “kill, kill, kill, kill, kill.” [18]. As students resisted oppressive actions and beliefs, police forces, along with the National Guard, retaliated with force and intimidation. A Ohio State University peer, Don T. Martin, also remembers police activity during the 1970 campus protests: “Throughout the student Anti-Vietnam War Movement much was said about the ‘theatrics’ displayed by student protesters in their resistance to authority; yet what was not appreciated was the fact that the authorities in their counter-resistance efforts possessed and utilized far more theatrical resources than did the student resisters. For example, to walk through the night emptied by curfew and patrolled by carloads of policemen armed with shotguns and gas-grenade launchers, to be hit with searchlights from overhead helicopters, to see tanks and armed authorities putting on their gas masks with some jeeringly gesturing at students with hippie-type dress and demeanor created a surreal setting.” [19] Although Brands mentions shootings at Kent State and Jackson State, police and National Guard occupation, intimidation, and violence occurred on various college campuses, including the Ohio State University, ultimately resulting in a “war” between students and authorities.

Eventually, overwhelmed by the growing number of student protesters, increased violence, and mass boycotts of class, the President of the Ohio State University made an announcement on May 6th, 1970 that the University would shut down for a short period of time. [20] Students disbanded with demands unmet as they were forced to leave their campus. When students returned on May 19th, security measures tightened, but activists continued to rally, establishing a 2,000-person protest on the day of return. [21] Despite this continuation of activism, graduation commenced and momentum eventually waned. [22] According to Weinberg, “We wanted to change the world…but we failed” [23] Although student activists at Ohio State University may not have achieved most of their goals as documented through their demands of the administration, they experienced some victories. For example, an Afro-American Studies department was established and efforts were made to start a daycare service free to University women. [24] In order to understand the experiences of student protesters at Ohio State University and elsewhere, their efforts must be viewed outside of the context of anti-Vietnam War boycotts. Although the anti-war effort was certainly important to people such as Weinberg, students also advocated for the rights of African Americans, women, and the general student body in the wake of immense resistance from university administration and police forces.

Clip from Marc Weinberg’s interview:

Footnotes

[1] Video Interview with Marc Weinberg, Frederick, MD, March 14, 2015.

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 170.

[3] Ibid, 170.

[4] Ibid, 152.

[5] Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones, Peace Now! American Society and the Ending of the Vietnam War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 43.

[6] Novice G. Fawcett and The Ohio State University Administration, “University Administration Responds to Student Demands,” September 29, 1970 [Ohio State University Archives].

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Diary of a Dilemma,” The Ohio State University Alumni Monthly, June 1970, 9 [Ohio State University Archives].

[10] Video Interview with Marc Weinberg, Frederick, MD, March 14, 2015.

[11] Jeffreys-Jones, 85.

[12] Video Interview with Marc Weinberg, Frederick, MD, March 14, 2015.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Melvin Small, Antiwarriors: The Vietnam War and the Battle for America’s Hearts and Minds (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources Inc., 2002), 102.

[16] Brands, 170.

[17] Video Interview with Marc Weinberg, Frederick, MD, March 14, 2015.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Don T Martin, “Reflections of a Graduate Student at Ohio State University During the Anti-Vietnam War Movement, 1965-1970,” American Educational History Journal 30 (2003): 1-5 [ProQuest].

[20] “Diary of a Dilemma,” 15.

[21] “Diary of a Dilemma,” 18.

[22] Martin, 1-5.

[23] Video Interview with Marc Weinberg, Frederick, MD, March 14, 2015.

[24] Fawcett and The Ohio State University Administration. “University Administration Responds to Student Demands.”