By Abby Marthins

In the heart of World War II, Jackie Loftus was only a child. She lived in Philadelphia with her mother, father, and older sister. When the war ended in 1945, she was just three years old. Although Loftus does not recall the war itself, she grew up hearing about her parents’ experiences. Both her mother and her father aided in the war effort. “My dad made gun shellings,” she explains, “and my mom stayed home. She was working for the soldiers, doing the cooking.”[1] Loftus does remember, however, how the war’s long-term effects impacted her childhood. She grew up practicing air raid drills and witnessing her family struggle to acquire enough food. “My mom was so hungry,” she claims, “and they didn’t have bacon or ham, so she would make onion sandwiches.”[2] While Loftus’s recollection adds depth to H.W. Brands’s description in American Dreams of everyday life in America during the World War II era, it also highlights several aspects that Brands overlooks.

World War II created many jobs for women. Although women had been in the work force prior to the war, their options were limited and did not require physical labor. When men left to serve in the war, their previous occupations became vacant, giving women the opportunity to step in. Brands claims that “during World War II women took jobs in shipyards and drydocks, on truck and airplane assembly lines, on road and bridge construction crews, among the girders and scaffolding of building sites.”[3] Brands’s interpretation aligns with Loftus’s recollection of women working during World War II. Loftus remembers, “My sister…knew somebody that did riveting…she worked in a factory. I guess it was for planes. The metal where they would rivet something together.”[4] This woman worked at an airplane assembly line, which became one of the most popular occupations among women in the war era. According to Kari. A Cornell in Women on the US Home Front, “In the years before the war, women made up a mere 1 percent of workers in this industry. By 1943, that number had skyrocketed to 65 percent.”[5] Brands also mentions that women had different motives for entering the work force during the war. “For some women the jobs were simply jobs, a means to put food on the table and a roof over the heads of themselves and their families,” he evaluates, “For others the new opportunities signaled an important advance toward gender equality.”[6] When asked about her sister’s acquaintance’s motive for getting a job at an airplane assembly line, Loftus mentions that she “was married with children and probably wanted to help support her family.”[7] Loftus confirms Brands’s analysis of women seeking jobs to support their families.

Woman prepares for a blackout drill (Women on the US Home Front)

Another result of World War II was the incorporation of safety drills in homes and schools. In fear of being attacked, the government ordered blackout drills and air-raid drills. During blackout drills, all lights were to be turned off. In the case of a bombing, people thought that aircraft would have a difficult time locating a city without light. There were many rules that civilians had to follow during these blackout drills. Newspapers, such as The Philadelphia Tribune, reiterated some of the regulations. “Persons are permitted to move about or sit on steps or porches during the blue period but not during the red alert,” the Philadelphia Tribune stated, “Smoking is permitted during blue periods, but smokers are not permitted to light matches or lighters. No smoking is permitted during the red alert.”[8] Loftus recalls participating in blackout drills. She explains, “When sirens went off…all the homes in the city had dark shades you’d pull down. They called them black shades. And you couldn’t have any light really coming through.”[9] Not only were there blackout drills, but people practiced air-raid drills in homes and schools. At home, families were encouraged to practice hiding under tables. Many families created supply kits and plans for shelter in case of an air raid. At schools, when an air-raid drill was in place, students were instructed to sit under their desks or against the wall in the hallway. “When we were in school after the war,” Loftus recalls, “there were rules that you had to follow. If the sirens went off while you were in class, you would hide under the desk…And it was a little scary…”[10] Loftus remembers the air-raid drills in a similar manner to Barbara Williams Roberts, who attended an elementary school in Clinton, New York during the war. She explains, “It was scary. I was still in grade school, and I remember hearing an airplane and looking up to see what it was. I think I expected the Japanese to bomb Clinton.”[11] Loftus and Roberts agree that the safety drills were a frightening and memorable aspect of everyday life during and after the war, but Brands fails to mention it.

Rationing was also a major result of World War II. With the nation at war, there was a high demand for many basic supplies like food, metal, paper, and gasoline. To combat the high demand for these supplies, the government initiated a rationing program that limited Americans’ purchases. Each person was allotted “points” in the form of stamps in a book. With each purchase, a person would have to hand over points. According to the National World War II Museum, “By the end of the war, about 5,600 local rationing boards staffed by over 100,000 citizen volunteers were administering the program.”[12] Loftus remembers this program. She remarks, “The government issued coupons. They were called ration coupons. And if you went to the store, you could only get maybe a small portion of butter or gas. So, it was the government controlling what you bought.”[13] One of the first items to be rationed was tires. Then gasoline and bicycles were rationed. Finally, sugar (which would be rationed until 1947), coffee, canned goods, meat, cheese, milk, butter, and other fats were rationed. Although rationing created a lack of supplies, it also allowed for creativity and the rise in certain products. In particular, “Macaroni and cheese became a nationwide sensation because it was cheap, filling, and required very few ration points. Kraft sold some 50 million boxes of its macaroni and cheese product during the war.”[14] Rationing was also complicated; newspapers, classes, and government organizations helped Americans. The Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger included a “Rationing Calendar” to assist Americans. The section read, “Here are the dates which it is important for you to remember in connection with the rationing program.”[15] It then listed several items and the expiration dates of their ration coupons. Brands does not include any details about the rationing program, even though it was a significant aspect of many Americans’ everyday lives.

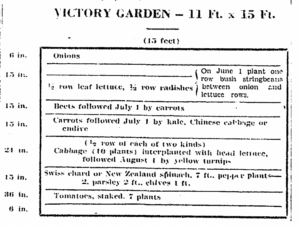

When the government incorporated the rationing program, it also encouraged many Americans to create gardens. These gardens were called “Victory gardens” and their outputs helped manage the shortage of food. According to the US Department of Agriculture, “9 to 10 million short tons of fruits and vegetables were harvested from Victory gardens during the war years—the same amount of veggies grown on commercial farms during that period.”[16] Loftus’s family participated in creating Victory gardens. “They’d make vegetables,” she describes, “I remember my uncle…he planted a lot of stuff like corn, watermelon, all kinds of stuff.”[17] Even Americans in cities were able to create Victory gardens. Places like San Francisco, Chicago, New Orleans, and Philadelphia were all homes to a plethora of Victory gardens. Living in Philadelphia, Loftus remembers what Victory gardens were like in cities. She explains, “Some people in the city didn’t have yards to plant stuff but they would have open fields and any place where they could plant stuff.”[18] The newspapers were also a source of information for and encouragement of Victory gardens. The Philadelphia Tribune included a section titled “Make City Backyards into ‘Victory’ Garden Plots” in which it embedded a diagram of a garden plot and gave advice such as “be sure to leave some space between the rows so that you may cultivate the plants.”[19] The Philadelphia Tribune also encouraged Americans to create Victory gardens by setting goals and holding contests. It read, “Last year 20 million gardens produced 8 million tons of food…the Victory garden goal for this year is 22 million gardens to grow 10 million tons of food,”[20] and “Conforming with the wish to the government, that amateur gardeners be encouraged to make more Victory gardens this year, the Tribune is inaugurating its second annual Victory garden contest.”[21] Victory gardens were an important part of everyday life for a lot of Americans; however, they are not mentioned by Brands.

Loftus’s recollection of everday life in America during World War II offers a lot more detail than Brands’s American Dreams. With a limited amount of space to discuss a large part of American history, it is easy to overlook many aspects. Since Brands focuses on the political perspective when discussing World War II, he is bound to omit the personal aspects of the war. Although Brands fails to consider the challenges of the home front during the war, the harsh emotions felt by many American should not be disregarded. “Times were really hard,”[22] Loftus remembers. “It was a really tough time,”[23] she mentions again.

[1] Zoom interview with Jackie Loftus, April 28, 2022.

[2] Zoom interview with Jackie Loftus, April 28, 2022.

[3] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 13.

[4] Zoom interview with Jackie Loftus, April 28, 2022.

[5] Kari A. Cornell, Women on the US Home Front (Minneapolis: Abdo Publishing, 2016), 34.

[6] Brands, 13.

[7] Email interview with Jackie Loftus, May 4, 2022.

[8] “Blackout Rules.” Philadelphia Tribune, Jul 17, 1943, pp. 9. ProQuest, https://envoy.dickinson.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fblackout-rules%2Fdocview%2F531732531%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D10506.

[9] Zoom interview with Jackie Loftus, April 28, 2022.

[10] Zoom interview with Jackie Loftus, April 28, 2022.

[11] Quoted in Cornell, 26.

[12] “Rationing.” The National WWII Museum, 2018, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/rationing.

[13] Zoom interview with Jackie Loftus, April 28, 2022.

[14] “Rationing.” The National WWII Museum, 2018, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/rationing.

[15] “December 23, 1942.” The Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger (1934-1969), Dec 23, 1942, pp. 9. ProQuest, https://envoy.dickinson.edu/loginqurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fdecember-23-1942-page-9-38%2Fdocview%2F1833143557%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D10506.

[16] Cornell, 44.

[17] Zoom interview with Jackie Loftus, April 28, 2022.

[18] Zoom interview with Jackie Loftus, April 28, 2022.

[19] “Make City Backyards into ‘Victory’ Garden Plots: Improve the Poor Soil with Ashes, Fertilizer; it’s Work but Full, Too.” Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Mar 13, 1943, pp. 8. ProQuest, https://envoy.dickinson.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fmake-city-backyards-into-victory-garden-plots%2Fdocview%2F531669058%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D10506.

[20] “22 Million Gardens Victory Garden Goal.” Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Mar 18, 1944, pp. 7. ProQuest, https://envoy.dickinson.edu/loginqurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2F22-million-gardens-victory-garden-goal%2Fdocview%2F531741123%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D10506.

[21] “It is again! the Tribune 2nd Annual Victory Garden Contest: For all the Backyard Gardeners.” Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Mar 11, 1944, pp. 8. ProQuest, https://envoy.dickinson.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fis-again-tribune-2nd-annual-victory-garden%2Fdocview%2F531694564%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D10506.

[22] Zoom interview with Jackie Loftus, April 28, 2022.

[23] Zoom interview with Jackie Loftus, April 28, 2022.

Americans’ Personal and Work Life During World War II

By Abby Marthins

“But during World War II women took jobs in shipyards and drydocks, on truck and airplane assembly lines, on road and bridge construction crews, among the girders and scaffolding of building sites.” (H. W. Brands, American Dreams, p. 13)

Interview Subject

Jackie Loftus, age 79, who recalls changes to personal and work life in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania during World War II

Interviews

–Zoom Call, April 28, 2022

Selected Transcript

Q: What was your family life like during World War II?

A: “World War II. My mom, at the beginning of the war, she was 28. Any my dad was 31. At the end of the war my mom was 34 and my dad was 37. And my sister wasn’t born in the beginning of the war, but at the end of the war she was five years old. And I wasn’t born in the beginning of the war, but I was three years old. So my mom stayed home. She was working for the soldiers, doing the cooking. Well, she was busy with two kids, not like your mom with seven.”

Q: Were there any major changes to peoples’ daily lives?

A: “Times were really hard…you couldn’t buy meat, you couldn’t get butter. And the government issued coupons. They were called ration coupons. And if you went to the store you could only get maybe a small portion of butter or gas. So it was the government controlling what you bought during that time because everything was a really tough time. For example, not everybody would get gas for their cars…it was like sacred. There wasn’t much available.”

Q: How would you get these ration coupons?

A: “My dad worked in a steel mill and they converted part of the steel mill to make ammo. My dad made gun shellings. He would make cannon shelling for the big tanks…out of steel. And he got coupons to go to work so he was lucky.”

A: “And also the women at home would have what they called ‘victory gardens.’ Everybody grew everything. From seed, vegetables, tomatoes, potatoes. And if you didn’t have a yard, like some people in the city didn’t have yards to plant stuff, but they would have open fields and any place where they could plant stuff. A lot of the people, and older men too I guess that weren’t involved in the war, they would help out with the victory gardens. They’d make vegetables, and even, I remember my uncle, my mom was telling me that he had a big yard so he planted a lot of stuff, like corn, watermelon, all kinds of stuff. But he also raised rabbits because meat was scarce. So they would eat rabbits. And the other thing is he would also sell them to people because meat was scarce. And I remember my mom saying that sometimes she was so hungry they didn’t have bacon or ham, she would make onion sandwiches. People were a lot thinner then.”

Q: What types of jobs did people have?

A: “Children worked at that time. I was talking to my sister and I talked to Uncle Dick, my sister’s husband, that him and his friend went out in the neighborhood and they took a wagon going from house to house looking for metal because they would save metal to melt down and use for something else. And I remember as a kid, it wasn’t during the war, but they saved everything at that time. Nothing went to waste. They had this man that would come around and he would collect rags. I could never figure out why he was saving rags or what they used them for. It was weird. But he would go through the streets and yell ‘Any old rags, any old rags!’ I don’t know what he did with them but that’s what I remember. And Aunt Jeanette, she would knit socks for the soldiers. And did you ever hear the word ‘Rosie the Riveter?’ A lot of women worked for the war cause too. They worked, of course my mom didn’t.”

Q: So your mom was more focused on taking care of you and your sister?

A: “Yes.”

Q: Did she have a previous job that she had to give up to help your family or the war?

A: “No. During that time, women didn’t work. It was just later in years that women started to go to work.”

Q: When men went to war a lot of women would take their jobs in factories. Do you know anything about that?

A: “My mom didn’t know anybody, but I was talking to my sister, she knew somebody that did riveting. She was like a ‘Rosie the Riveter.’ She worked in a factory. I guess it was for planes. The metal where they would rivet something together. I don’t know what they did.”

Q: Do you know if she had to leave a job to do that?

A: “Most likely not. Women did work because I remember my mom before she got married was a telephone operator. So I’m sure some women worked. Other women with children obviously stayed home and cooked for their man. I think that everyone at that time would work together for gold to help the war effort basically. Everybody saved something, everybody made something, worked for a cause. They worked for the war effort. And as I mentioned, at that time everything was saved. They used everything. Nothing was wasted. Nothing. Like paper. They even saved stamps from letters and would send them to the soldiers so they could collect them and say ‘Ooo look I have a stamp from Canada’ and that’s where all collecting and saving stamps came from.”

Further Research

- Claudia Goldin and Claudia Olivetti, “Shocking Labor Supply: A Reassessment of the Role of World War II on Women’s Labor Supply,” American Economic Review, vol. 103, no. 3, May 2013, pp. 257–62. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.3.257.

- Natsuki Aruga, “‘An’’ Finish School”,’” Labor History, vol. 29, no. 4, Fall 1988, p. 498. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1080/00236568800890331.

- Char Miller, “In the Sweat of Our Brow: Citizenship in American Domestic Practice During WWII—Victory Gardens,” Journal of American Culture, vol. 26, no. 3, Sept. 2003, pp. 395-409. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1111/1542-734X.00100.

- Stephen W. Sears, “Sorry No Gas,” American Heritage, vol. 30, no. 6, Oct. 1979, pp. 4-17. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx direct=true&db=31h&AN=20863705&site=ehost-live&scope=site.