Vietnam Through A Veteran’s Eyes

Sam Schmidt, History 118

One November morning in 1968, twenty-five-year-old Jerry Begley disembarked from a military aircraft at Travis Air Force Base in California. He and a cohort of other young veterans were thanking their lucky stars for returning home from Vietnam in one piece. Buses whisked the tired troops to San Francisco International Airport for their flights home. None of them anticipated that they would soon be intercepted by the city’s many antiwar protesters. “We were there at three o’clock in the morning”, Begley recalls incredulously, “and there were lots of protesters”.[1] The bus driver promised to drop the veterans as close to the door as possible as the protesters began to approach the buses. As their bus neared the entrance, Begley remembers, “The protesters…[were] throwing stuff against the buses…[then] we got off. I didn’t get hit with anything. Some guys got hit with eggs. We got inside and from that point on, then everything was okay”.[2]

Whatever Begley and the other Vietnam veterans expected of their return, surely it was not bitterness from their own countrymen. Begley had guarded convoys, patrolled the streets of Saigon, and defended the American Embassy during the Tet Offensive of 1968. He had involuntarily weathered twelve months of harsh and dangerous Army life at the nexus of one of the most controversial foreign-policy engagements in American history. In his book American Dreams: The United States Since 1945, H.W. Brands says that Vietnam “seared itself onto the American mind”.[3] Brands’ own coverage of the Vietnam War is appropriately detailed and complex. However, it does not fully encapsulate the experience of Vietnam veterans like Begley, who fought and returned home only to often find themselves relegated to the fringes of both collective memory and any discussion of the war.

Click above for background on Vietnam and Begley’s thoughts on the conflict before his service.

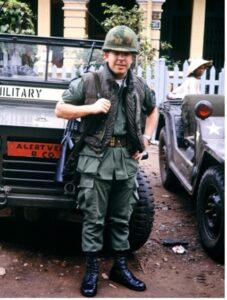

Begley was drafted into the Army in 1966 and arrived in Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, in late 1967, where he worked as an MP (military policeman). Cycles of routine security patrols soon devolved into the war’s turning point: the 1968 Tet Offensive, wherein a supposedly handicapped Viet Cong coordinated elaborate attacks across South Vietnam. Begley and other MPs witnessed Viet Cong sappers bomb the US Embassy; Brands calls this event the “handwriting on the…wall” for the war’s future.[4] Begley says he realized then that the war was a “losing affair”, despite assurances otherwise from the military brass.[5] Brands similarly contends that many U.S. generals acted unfazed by the offensive.[6] However, this posturing was belied by changes in policy on the ground. Before the offensive, Begley was instructed, “We were told to respect the Vietnamese…and only return fire. We couldn’t shoot first. After [Tet], it was different. All of that went away”.[7] Brands effectively corroborates this situation, recalling Marine Philip Caputo’s encounters with frightened Vietnamese confronted with forceful American suspicion.[8] Already-wary American troops had to treat the people they were supposed to defend as foes. The war had taken a turn, and not for the better. However, Begley was out by November 1968. He had been fighting the Vietnam War a world away; he returned to a country fighting itself over the deteriorating situation there. He had not chosen Vietnam service, but he now found himself representing the divisive war, for better or worse.

The airport reception was the only antiwar protest Begley ever witnessed. San Francisco specifically was a hotbed of pacifist activism at the time, which Brands connects to the growing 1960s counterculture movement.[9] Condemnation of the war varied from complex accusations of imperialism to simple moral outrage. Verified accounts of the directly anti-soldier protests Begley saw are uncommon. However, Begley remembers an officer warning his bus cohort to ignore the insults and projectiles, knowing that any reaction would play into the protesters’ hands.[10] Evidently, this was a repeat experience for the officers. However, the situation for returning veterans varied significantly, and it remains a source of debate.

Accounts of veteran-protester interactions like Begley’s form a complex tapestry. The sociologist Jerry Lembcke asserts that the infamous stories of protesters spitting on returning veterans were likely fictitious.[11]Brands doesn’t really weigh in on these events, only offering vague accounts of Vietnam veterans participating in a diverse march on the Pentagon.[12] Begley never protested the war, and he was not sympathetic of the protesters: “I thought they were totally wrong, because they’re protesting the soldiers that were there under orders. We didn’t make the decision to go there”.[13] Jerry’s return to conservative rural Iowa was much warmer, and most veterans likely didn’t experience what he had in San Francisco.[14] But it was still not the welcome many had hoped for. 53 percent of surveyed Vietnam veterans called the often-lukewarm reaction to their return a “big letdown”; 79 percent agreed that people “just didn’t understand” what they had endured.[15]Jubilant parades welcoming returning WWII veterans still loomed large in the national memory; many Vietnam veterans glumly wondered where that sentiment had gone.

The country debated Vietnam until its end, but evidently, many veterans simply felt shut out of that discourse. Brands never really covers their postwar experience. Of course, he cannot document everything, but he gives significant attention to WWII veterans and their role in the growing postwar economy, from the demobilization to the GI Bill to the baby boom.[16] Although he assures the reader that people simply wanted to move on from WWII, one wonders if that sentiment is really more applicable to Vietnam.[17] WWII had vindicated America’s economy, military might, and national spirit. The ever-decaying effort to prop up South Vietnam was fostering little more than doubt about all three. But whatever the case, life moved on back home.

Begley finished another year of service in Chicago before returning to Springville, Iowa, in 1969. He settled into a job and started a family. He didn’t discuss his service much afterwards. “Military service was respected” there, Begley remembers.[18] However, he also recalls, “For a long time you would hear the occasional comment about drugged-up Vietnam vets”.[19] Begley says he never saw hard drug use in Vietnam, although he concedes that his fellow MPs, as enforcers, would be less likely to partake.[20] Nonetheless, drugs were very present in Vietnam, and fed a common stereotype of the troops as demoralized, lazy junkies. Brands somewhat feeds this narrative of chronic addiction among the troops, citing a 1971 report alleging that one-sixth of the Vietnam force was addicted to heroin.[21] Epidemiologist Lee Robins disputed this assertion, also noting that Vietnam veterans rarely resumed drug use once home.[22] These comments, probably coming from Iowan conservatives who likely supported the war, reflect the social complexities of the time. The rising tide of drug alarmism was adopted by Nixon in 1971 in the “War on Drugs”, and many citizens flinched to see drugs proliferate in the proud U.S. Army. Desertions, heroin, crumbling resolve? What had become of the Vietnam war effort?

The unpopular and unsuccessful war did not last much longer. In 1973, the U.S. withdrew its last troops from South Vietnam; by 1975, the North Vietnamese communists overran the country and negated nearly two decades of American effort. Begley’s second daughter was a toddler by then. Besides the home loan, his service was fading into the background. Indeed, he recalls little reaction to the war’s end. He was happy to see long-imprisoned American POWs freed, but otherwise he recalls thinking, “The war’s over now…put it behind us, I guess”.[23]

Evacuation of the US Embassy in Saigon, 1975. Begley helped to defend this building during the Tet Offensive in 1968. (PBS)

Many Americans certainly wanted to put Vietnam behind them. Lembcke calls the loss a “tough pill to swallow”, particularly given the lingering triumphalism of WWII.[24] Jerry reflects, “It was definitely a waste of 58,000 American lives. Definitely a waste of tons of material…and a bunch of money. To prove nothing”.[25] If the war proved anything, it was that the U.S. was not an omnipotent power. As Brands puts it, Vietnam unveiled the lesson that “When in doubt, America must not [fight]”, a stark reversal of the hyper-vigilant anticommunism of the early Cold War.[26] The country is still yet to fight another war on Vietnam’s scale.

Scale defined the Vietnam War. The commitment of 2.6 million soldiers, 58,000 lives, and some one trillion 2023 dollars was precisely what made the loss so harsh.[27] Brands’ book covers grand figures and broad trends in American history like these, and for good reason. However, the individual stories of the war are equally valuable. They have often been defined by political strife, memories of addiction and desertion, or just the defeatist pity of an ugly loss. As with all wars, though, life went on. Begley himself worked, raised two daughters, traveled the world, and enjoys a comfortable retirement today. His service did not define him, but neither is it invisible. However unpleasantly forgettable Vietnam proved to be, it was an experience that personally impacted millions of Americans. Brands is right to argue that Vietnam “seared itself on the American mind”.[28] It divided and challenged the country in more ways than historians can expect to document, stirring both the unfamiliar fidgeting of loss and the militant fires of protest. Americans both immortalized the war and tucked it away. Begley balances these instincts. “The war probably shouldn’t be remembered,” he reflects. “The people that lost their lives, like the Vietnam War tribute wall, that’s very appropriate. The only memory I would cherish would be the wall”.[29] And neither can the living be forgotten.

Begley (far left) and other veterans revisit the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 2023. It commemorates 58,276 soldiers who gave their lives in Vietnam. Currently, it is estimated that over 500 Vietnam veterans die every day. [30] (Russell Hons Photography)

[2] Ibid.

[3] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York, Penguin Books, 2010), 175.

[4] Ibid., 155.

[5] Brands, 175.

[6] Brands, 157.

[7] Video Interview with Jerry Begley, Carlisle, PA, and Stalker Lake, MN, December 4, 2023.

[8] Brands, 143-145.

[9] Ibid., 147.

[10] Video Interview with Jerry Begley, Carlisle, PA, November 27, 2023.

[11] Jerry Lembcke, “The Myth of the Spitting Antiwar Protester,” The New York Times, October 13, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/13/opinion/myth-spitting-vietnam-protester.html. [Google]

[12] Brands, 154.

[13] Video Interview with Jerry Begley, Carlisle, PA, November 27, 2023.

[14] Email Interview with Jerry Begley, December 4, 2023.

[15] Loch Johnson. “Political Alienation Among Vietnam Veterans,” The Western Political Quarterly 29, 3 (September 1976): 398-409, https://doi.org/10.2307/447512. [JSTOR]

[16] Brands, 13, 17, 27, 69, 78.

[17] Ibid., 22.

[18] Email Interview with Jerry Begley, Carlisle, PA, December 4, 2023.

[19] Video Interview with Jerry Begley, Carlisle, PA, November 27, 2023.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Brands, 170.

[22] Lee N. Robins et al., “How Permanent Was Vietnam Drug Addiction?,” American Journal of Public Health 62, 12 (December 1974): 38-43, 10.2105/ajph.64.12_suppl.38. [PubMed Central]

[23] Video Interview with Jerry Begley, Carlisle, PA, November 27, 2023.

[24] Lembcke, 2017.

[25] Video Interview with Jerry Begley, Carlisle, PA, November 27, 2023.

[26] Brands, 175.

[27] “The War’s Costs”, Digital History, 2021, https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtid=2&psid=3468.

[28] Brands, 175.

[29] Video Interview with Jerry Begley, Carlisle, PA, November 27, 2023.

[30] Mary Jordan and Kevin Sullivan, “The Unclaimed Soldier: A Final Salute for the Growing Number of Veterans Who Have No One to Bury Them,” The Washington Post, November 11, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/11/11/unclaimed-soldier/ (accessed December 1, 2023). [Google]

[31] Video Interview with Jerry Begley, Carlisle, PA, November 27, 2023.

Appendix I: Additional Photos

Marines resting after a Tet Offensive battle, one of some 120 that occurred across the country in late winter 1968. (Associated Press)

Celebratory parade in Seattle for returning troops, 1969. Such pictures of returning troops are rare, and none exist of the protests Begley encountered. (HistoryLink)

Begley in 2023 returning from an Honor Flight. These trips to Washington, D.C. are provided free of cost to veterans. Jerry described the celebratory welcome as “something I’ve never experienced before”.[31] (Russell Hons Photography)

“The vain struggle…seared itself on the American mind” (H.W. Brands, “American Dreams”, 175)

Interview subject: Jerry L. Begley, age 80, former U.S. military policeman, served at American Embassy in Saigon, South Vietnam from 1967-1968 before returning to the U.S. and reentering civilian life in his home state of Iowa.

Zoom Interview with Jerry L. Begley from Carlisle, PA and Stalker Lake, MN, November 27, 2023.

Q: What were your feelings on the Cold War in general before your service?

A: I agreed with the [containment doctrine] in my own evidently, perhaps naïve way sometimes, but yeah, I thought it was the right thing to do, because we didn’t want Soviet aggression in all those countries. So I thought that was okay.

Q: What were your feelings on military service before and during your being drafted?

A: I wouldn’t have decided to [volunteer]. But when I entered military service, it was still okay. It was a Midwestern thing to do. There was no protests going on of the war – in Iowa, anyway. Okay, so yeah, we’ll go do this. It was the thing to do.

Q: How did your views of the war evolve during your service?

A: Initially, I thought, this is what we gotta do, I’m in the army, I’ll do what I’m told to do. But I was there during the Tet Offensive on January 31st, 1968, at that time, what I would call a disconnected NVA and Viet Cong army overran military installations, they bombed the embassy [in Saigon]. And from that point on, I thought, if they can still do this in 1968, we’re never going to defeat them. That turned a lot of people against the war, and us also, because if they continue to do so, this is going to be a losing affair…it was definitely a waste of 58,000 American lives. Definitely a waste of tons of material…and a bunch of money. To prove nothing.

Q: What was your experience with commonly narrated tropes about Vietnam veterans: drugs, desertion, violence, et cetera? Did you experience this?

A: There wasn’t much drug use within the MPs because if you got caught, you were out the door to [an] infantry unit or whatever…but there was drug use amongst troops…There were desertions in Vietnam amongst troops. As a matter of fact, our military police unit would conduct raids at times on a refugee area just outside of Saigon where deserters were known to stay. So we’d go in there and search that and yes, we’d find some deserters. I didn’t really feel [any emotion either way about that]…it was just a job. A couple I remember in particular were just plain afraid of the war. They weren’t mad or anything. They were just afraid…they were young guys – they were just afraid.

Q: What were the reactions to your service when you came home?

A: I flew into Travis Air Force Base in California to get processed out and then we went from there in buses to the San Francisco International Airport. There were protesters outside the Travis Air Force Base, protesting us and throwing stuff against the buses and stuff. We got to San Francisco International, and we were there at three o’clock in the morning. And there were lots of protesters there…so we got off [the bus]. I didn’t get hit with anything. Some guys got hit with eggs. We got inside and from that point on, then everything was okay. So after that, I came back to Iowa. There was no protesting in Iowa. Every once in a while you’d hear some comments about some drugged-up Vietnam vets, but there wasn’t any protesting.

Q: What did you think of the protests?

A: No I thought they were totally wrong. Because they’re protesting the soldiers that were there under orders. We didn’t make the decision to go there…the politicians made those decisions. And that was the general feeling. Why do they want to protest us? And you’d hear terms like “baby killers” and all that, and that may well have happened, but they were protesting our involvement in the war.

Q: How did you feel about the conclusion of the war after you had come home?

A: As part of the peace accord…they got to bring all the POWs home…I thought, that’s wonderful…[Otherwise] the war’s over now. They’re home safe. But uh, put it behindd behind us, I guess.

Q: How did you feel about how Vietnam should be remembered?

A: The war probably shouldn’t be remembered. The people that lost their lives, like the Vietnam War tribute wall that’s now up to them, that’s very appropriate. Everything else…yeah. The only memory I would cherish would be the wall.

Further Research:

Boyle, Brenda M. “Naturalizing War: The Stories We Tell about the Vietnam War” In Looking Back on the Vietnam War: Twenty-first-Century Perspectives, 175-192. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2016. [JSTOR]

Michael Clark. “Remembering Vietnam,” Cultural Critique 3, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 46-78. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354165. [JSTOR]

- Drummond Ayres Jr, “Army Is Shaken by Crisis In Morale and Discipline,” The New York Times, September 5, 1971. https://www.nytimes.com/1971/09/05/archives/army-is-shaken-by-crisis-in-morale-and-discipline-army-is-shaken-by.html (accessed November 15, 2023). [New York Times Archive]

David Flores. “Memories of War: Sources of Vietnam Veteran Pro- and Antiwar Political Attitudes,” Sociological Forum 29, no. 1 (March 2014): 98-119. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43653934. [JSTOR]

Eric T. Jean, Jr. “The Myth of the Troubled and Scorned Vietnam Veteran,” Journal of American Studies 26, no. 1 (April 1992), 59-74. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27555590. [Article, Waidner-Spahr Library]

Loch Johnson. “Political Alienation Among Vietnam Veterans,” The Western Political Quarterly 29, no. 3 (September 1976): 398-409. https://doi.org/10.2307/447512. [JSTOR]

Jerry Lembcke, “The Myth of the Spitting Antiwar Protester,” The New York Times, October 13, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/13/opinion/myth-spitting-vietnam-protester.html (accessed November 15, 2023). [Google]