Image Gateway

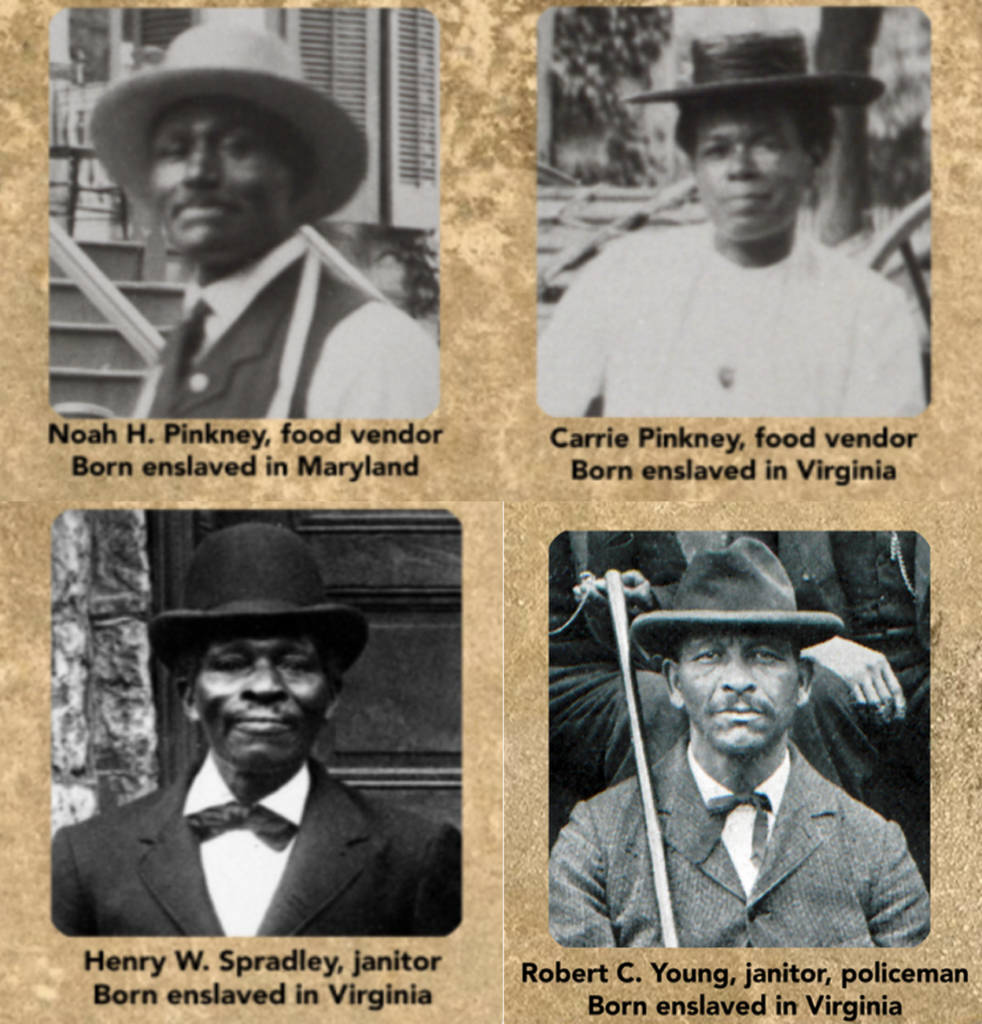

For more information, see Freedom’s Legacy at Dickinson & Slavery and watch this video with the descendants of Henry Spradley and Robert Young.

Discussion Question

- Did the Second Founding of the Constitution (1865-70) succeed in transforming American society?

Thirteenth Amendment (JAN 1865 / DEC 1865) Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

ORIGINS: Northwest Ordinance (1787) Art. 6: There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted…

Fourteenth Amendment (1866 / 1868) Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

ORIGINS: Civil Rights Act of 1866 SEC. 1: That all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States;

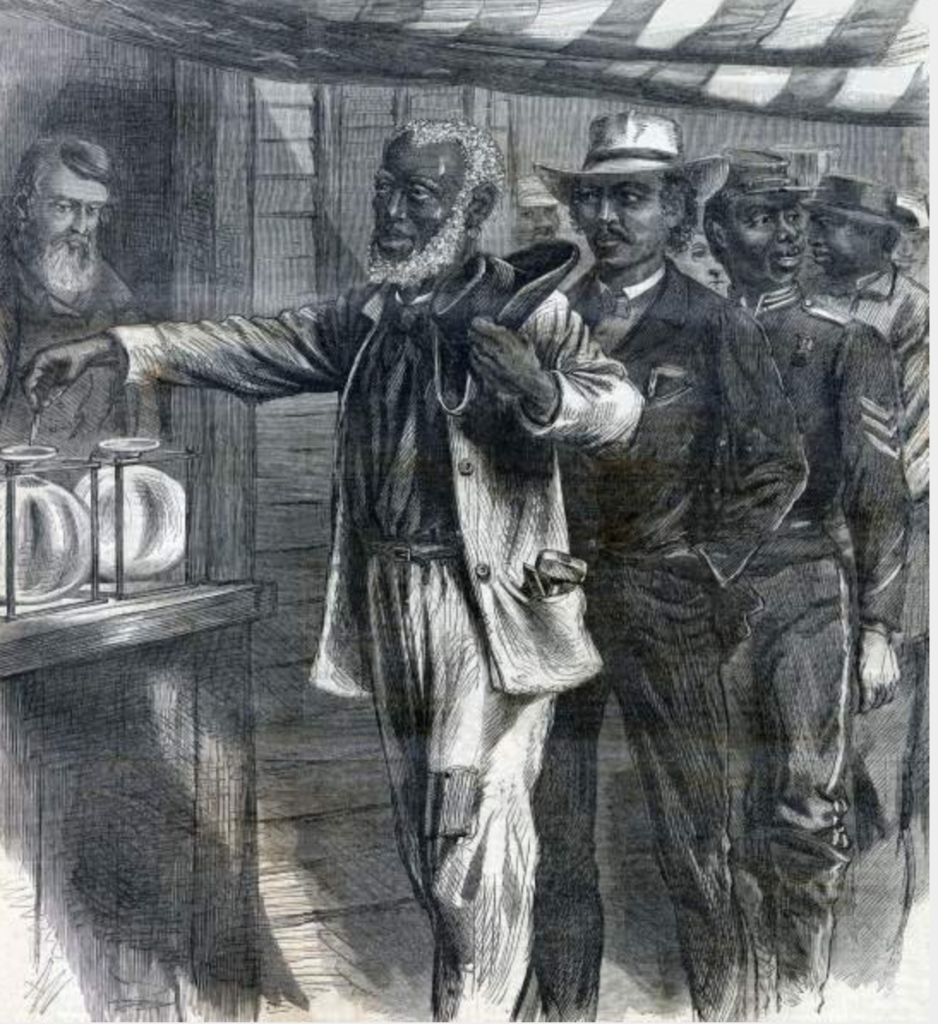

Fifteenth Amendment (1869 / 1870) Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

ORIGINS: Reconstruction Act (1867) SEC. 5: And be it further enacted, That when the people of any one of said rebel States shall have formed a constitution of government in conformity with the Constitution of the United States in all respects, framed by a convention of delegates elected by the male citizens of said State, twenty-one years old and upward, of whatever race, color, or previous condition

Featured Supreme Court Decisions

- Civil Rights Cases or US v. Stanley (1883): “When a man has emerged from slavery, and, by the aid of beneficent legislation, has shaken off the inseparable concomitants of that state, there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws, and when his rights as a citizen or a man are to be protected in the ordinary modes by which other men’s rights are protected.” (Majority opinion by Justice Joseph Bradley)

- Plessy v. Ferguson (1896): “The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in power…. But in the view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” (Dissent by Justice John Marshall Harlan)