By Cole Pellicano

“The 1950s were the heyday of the modern corporation. Detroit’s Big Three- General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler- were models of stability and steady growth.”- (H.W. Brands, American Dreams, p. 71)

“Manufacturing, having supplanted farming as the signature occupation of the American people around the turn of the century, remained the beating heart of the economy, but a growing segment of the workforce provided services.” – (H.W. Brands, American Dreams, p. 72)

Jerry Emerson was just like every other baby boomer of his time, a young adolescent trying to find work in the postwar era. Emerson recalled, “On the farm you could never get more than thirty hours a week. Our Chrysler factory opened in fifty-five and offered the most pay in the area.”[1] H.W. Brands expresses the idea that the “Big Three” automotive makers of Detroit were symbols of stability and growth. However, after conducting research and interviewing Emerson, there is evidence that challenges Brands’ claim and portrays a different angle of the automotive industry throughout the postwar era. Through the descriptions of the earliest Chrysler factories, the bailout the company faced in 1979 and the foreign production that would cripple the company completely. By the turn of the twenty-first century, the Chrysler Corporation was anything other than stable.

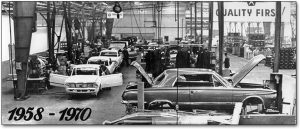

When World War II ended, a wave of domesticity crashed over America, and with this wave came a surge in the demand for automobiles. The “Big Three” companies, General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler received this wave with open arms.[2] Facing high demand, the assembly line was vital to the manufacturing of cars at this time. The increase of demand for Chrysler’s cars led to a much tougher life for the men and women on the assembly line. Low level workers were starting to become severely mistreated across the entire auto industry. It was this mistreatment of employees that would eventually lead to the formation of the Union of Automotive Workers (UAW).[3] The UAW was formed to eliminate the mistreatment of assembly line workers and relieve some of the pressure on lower level managers. In 1937, the UAW had their first organizational drive, it ended up being a major success.[4] The drive won the Union recognition from General Motors and the Chrysler Corporation. By bringing Chrysler and General Motors to terms, the UAW was able to put itself on the map.[5] Since it’s recognition, the UAW has won privileges for assembly line workers that would have never been gained had the workers fought alone. These privileges could consist of anything between lengthening lunch breaks to a bump up in pay. When WWII ended, the baby boom spiked America’s population and eventually created a working class larger than any before.[6] It was within this group of baby boomers that Emerson found himself applying to the Chrysler Corporation. Although the Union had gained national recognition, the fight for automotive workers was not over. There still remained a shortage of breaks, poor factory quality, and workers were not given the proper safety equipment. However, people of the post war era needed to find jobs and the automotive industry was notorious for providing a large amount jobs and good pay. This is what attracted Emerson to work for Chrysler in 1966.[7] Emerson claimed that everyone was interested by the Chrysler Corporation after the war, “People were constantly asking me what it was like to work there and if there was any availability.”[8]

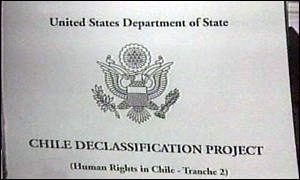

Although Brands described the “Big Three” as stable, Emerson’s experience with the company was quite unstable. Emerson worked for Chrysler from 1966-2000 and speaks very highly of the work that the UAW did during his time on the line. When first asked about his experience with the UAW, Emerson said, “If it wasn’t for the UAW we wouldn’t have gotten a decent wage, safety improvements, any type of job security, or a decent retirement plan.”[9] However, it seemed that during his time at Chrysler, there still had not been any major changes to how workers were treated or the quality of the factories. Emerson described the factories as, “horrible…hot, dusty, and dirty,” and later saying that they were treated as disposable by management.[10] Managers were also distanced from the workers, they were given a number of cars to produce and would meet that quota by any means necessary.[11] Safety was never a priority and workers were never standing still, Emerson explained, “We used to joke around by calling ourselves the hourly dogs.”[12] Throughout his career, Emerson eventually became a Union official for the UAW and was able to have a first hand vote in some of the negotiations for better work quality and help be a voice for his fellow employees. Emerson encountered many experiences in his time at the Chrysler Corporation that were not astray from the trends of general history. Every three years the UAW would do a progress evaluation at various plants across the country. If it had been a good three years the union would make a push for more rights, if it had been a bad three years, the union would struggle to even keep previous rights.[13] Emerson was able to recall vivid memories of some of these three year evaluation meetings. Emerson commented “You never wanted to be a part of one of those negotiations after a bad three year mark, I only sat in on one evaluation in my time, but I was one of the lucky ones that got an evaluation after three positive years.”[14] Emerson also was a part of the Chrysler Corporation during the Chrysler Bailout of 1979. The Chrysler Bailout of 1979 was the first major hit Chrysler took in its tenure.[15] Out of fear of being overrun by foreign importers, Chrysler attempted to take its operation overseas.[16] Unfortunately, the Chrysler European division failed miserably, Europeans did not share the same love that Americans had for Chrysler’s American muscle look.[17] Chrysler was forced to ask the government for a loan, the government granted the loan, but not without requiring major federal involvement. Emerson recalled his experience of the bailout, “They kept us in the dark, especially us UAW workers, they didn’t want us asking questions, the worst part was that the only thing that wasn’t in the dark was the dollar and a half that came off of our hourly pay, that definitely hurt.”[18] At the end of his career at the Chrysler Corporation, the company had begun a steep downhill decline. The 1980’s and the turn of the twenty-first century brought with it an oil crisis that would allow foreign car companies with incredible gas mileage to dominate the market.[19] This was the last hit Chrysler could withstand, they simply could not keep up with the foreign importers that were now the new American favorite. Emerson claimed, “People wanted better gas mileage which allowed the Japanese to market how great their gas mileage was, by the time we caught on to that it was too late, the Japanese were very smart for that.”[20]

There are many major events that happened over the course of Emerson’s time at Chrysler that enable a transparent look into what life truly was like on the assembly line at one of the “Big Three” corporations. Emerson’s memories are so important due to the fact that he had a first person experience as an employee and labor union official in the postwar era. Emerson was a part of a Union that gained national recognition in 1937, almost thirty years before he joined the work force. Even in today’s society, the UAW is still relevant and fights for assembly line workers’ rights in the auto industry. This allows for a different perspective of history that Brands is unable to truly capture. In today’s society, when people recall the “Big Three,” the idea of three corporate giants that are rooted in American culture is conceived. What people don’t get to see is the true practices that these corporations used to achieve their wealth, or eventual downfall in the case of Chrysler. The transcripts also give insight for people to see the undercover horror that these assembly line workers had to go through on a day to day basis. Emerson’s experiences can also be correlated with literary works. In Kevin Boyles novel The UAW and the Heyday of Liberalism, Boyle discusses functions of the UAW in the postwar era that are reflected by Emerson’s personal experience as a UAW official. Emerson’s memories allow for insight into a lifestyle that was not irregular for the postwar time period and is why it challenges Brands’ claim.

H.W. Brands claims that corporations such as the “Big Three” of Detroit were symbols of the modern corporation due to their stability and growth. After closer research and analyzing the transcripts provided by Emerson, it can be argued that corporations such as Chrysler were not as modern and stable as Brands claims. Emerson offers a closer look into the Chrysler Corporation that Brands would never be able to attain. The auto industry’s poor treatment of employees and lack of rights was far from how a modern corporation in today’s society would treat its employees. If it had not been for the UAW and its officials like Emerson, the workers would have been treated even worse.[21] Along with a lack of modernistic ideas, Chrysler was unable to make it to the twenty-first century without being merged with Mercedes Benz and eventually Fiat.[22] These facets joined together challenge Brands’ portrayal of the “Big Three” as being signs of stability and growth.

[1] Audio Interview with Jerry Emerson, November 7, 2017.

[2] Kevin Boyle, The UAW and the Heyday of American Liberalism 1945-1968 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995) [Dickinson Library]

[3] Kevin Boyle, Rite of Passage (Labor History 27 no. 2) [Google Books]

[4] Kevin Boyle, Rite of Passage (Labor History 27 no. 2) [Google Books]

[5] Kevin Boyle, Rite of Passage (Labor History 27 no. 2) [Google Books]

[6] Ronald Freeman on American Population Growth: A View from 1957 (Population and Development Review) [Ebsco}

[7] Audio Interview with Jerry Emerson, November 7, 2017.

[8] Audio Interview with Jerry Emerson November 7, 2017.

[9] Audio Interview with Jerry Emerson November 7, 2017.

[10] Audio Interview with Jerry Emerson November 7, 2017.

[11] Kevin Boyle, Rite of Passage (Labor History 27 no. 2) [Google Books]

[12] Audio interview with Jerry Emerson December 4, 2017.

[13] Kevin Boyle, The UAW and the Heyday of American Liberalism 1945-1968 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995) [Dickinson Library]

[14] Audio interview with Jerry Emerson December 4, 2017.

[15] James M. Bickley Chrysler Corporation Guarantee Act of 1979: Background, Provisions, and Cost (Ithaca NY: Cornell University, 2008) [Digital Common]

[16] Charles K Hyde Riding the Rollercoaster: A History of the Chrysler Corporation (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2003) [Google Books]

[17] Charles K Hyde Riding the Rollercoaster: A History of the Chrysler Corporation (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2003) [Google Books]

[18] Audio Interview with Jerry Emerson December 4th 2017

[19] Charles K Hyde Riding the Rollercoaster: A History of the Chrysler Corporation (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2003) [Google Books]

[20] Audio Interview with Jerry Emerson December 4th 2017

[21] Kevin Boyle, The UAW and the Heyday of American Liberalism 1945-1968 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995) [Dickinson Library]

[22] Charles K Hyde Riding the Rollercoaster: A History of the Chrysler Corporation (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2003) [Google Books]

Timeline

Selected Transcript

From Phone call on November 7, 2017

Q. Can you describe for me what the factory was like?

A. In one word, horrible, we were treated as disposable by the management, but we needed the money. You typically worked five eight-hour days and you were constantly moving. It was hot, dusty, dirty. There was no such thing as ergonomics. The safety was non-existent, we were at risk every day. I’ll give you an example, one of my good buddies Mel Underwood went to work every day and sprayed the carriages under the cars with this lubricant. They never gave Mel respiratory gear to keep the harmful fumes out of his lungs. He was forced to wrap his face with old towels and t-shirts. In the end, the damn stuff ended up being what killed him. Same thing with my good buddies that worked in the tire durability station of the line. They would spin the wheels and burn rubber and I swear these rooms would fill with smoke you couldn’t even see into them. They never got any safety gear for that, not until a few years down the road they added some ventilation. However, that didn’t come until Nixon signed OSHA into law. OSHA definitely helped a decent amount with safety inspections, but like I said that wasn’t until the seventies. If you saw a problem, management didn’t want to hear about it, all they wanted was to see sixty cars roll out the door every hour.

Q. What do you remember about the UAW(United Automobile Workers)?

A. What don’t I remember would be a better question. If it wasn’t for the UAW we wouldn’t have gotten a decent Wage, not as many safety improvements, any type of job security, or a decent retirement plan. By the way, I was an appointed Union official in the joint union and management division of the quality program. That was designed to give the hourly employees some input to help ensure quality.

From Phone call on December 4, 2017

Q. What do you recall about the Chrysler bailout of 1979?

A. We took a big hit, they kept us in the dark, especially us UAW workers, they didn’t want us asking questions, the worst part was that the only thing that wasn’t in the dark was the dollar and a half that came off of our hourly pay, that definitely hurt.

Q. What were labor management relations like during your years at Chrysler?

A.You never had a relationship with your manager, they were the bosses we were the workers. We used to joke that we were the hourly dogs, you may have liked the guy but never had a great relationship. It wasn’t until after the bailout that we as workers were able to have a say in the quality of car parts. It was a part of the product quality improvement program, which was used as more of a marketing strategy. Besides making sure you had the right tools, you would do what they say and sometimes make a suggestion.