Was the 1950s a “golden age” or more of a nightmare?

Brands, Chapter 4: Golden Age of the Middle Class, 1955-1960

- Boom! (pp. 68-70)

- General Eisenhower, Meet General Motors (pp. 70-73)

- The Magic Kingdom and the King (pp. 73-76)

- Our Town, Your Town (pp. 76-78)

- Men in Gray Flannel Suits (pp. 79-81)

- On the Road (pp. 82-84)

- From the Back of the Bus (pp. 84-88)

- Before the Eyes of the World (pp. 89-91)

- Reheating the Cold War (pp. 91-94)

- The Heavens Above (pp. 94-97)

- A Cold War Complex (pp. 97-99)

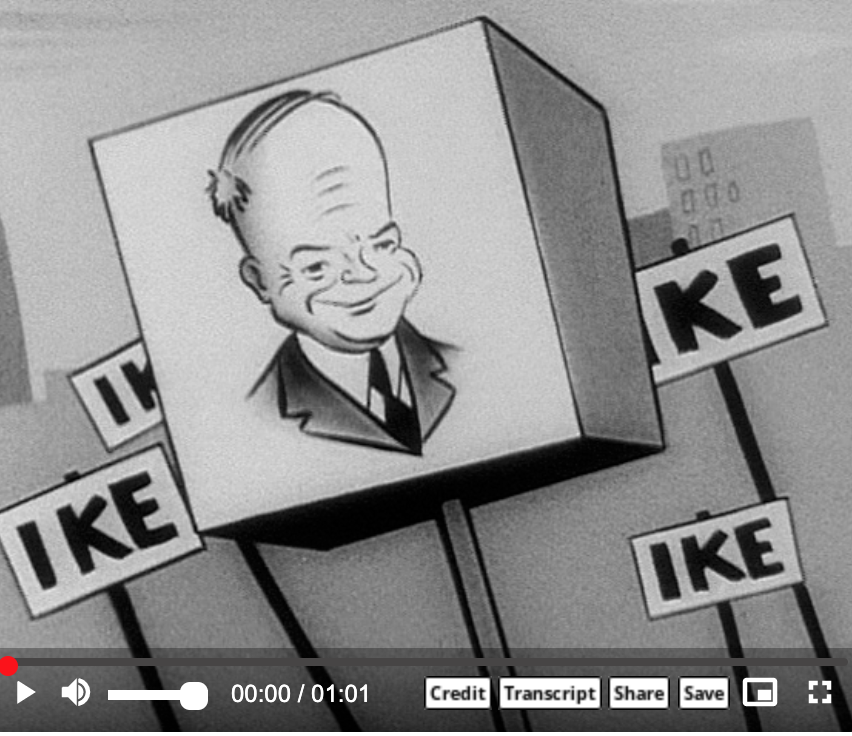

Image Gateway

Try to analyze these 1952 Eisenhower commercials courtesy of The Living Room Candidate.

Overview

H.W. Brands labels his chapter on the 1950s as “The Golden Age of the Middle Class,” but even Brands seems unsure how much to believe in this label. Were the Fifties a “Golden Age,” or a new “Gilded Age,” or more ominously, still the “Dark Ages” for race and gender discrimination? There were certainly real signs of widespread growth and prosperity for the American nation in this defining post-war decade, but also significant underlying tensions and growing social problems. Trying to fit all of these trends into a single narrative is challenging, but students in History 118 should be able to explain the contours of the period with a series of notable examples.

Baby Boom

The starting point might well be a consideration of population growth and the cultural consequences of the celebrated “Baby Boom.” US population soared between 1940 and 1960, from about 132 million people to over 180 million. The country gained about 30 million people during the 1950s alone –roughly equivalent to the entire population of Civil War era America. During this era of limited immigration (between the 1924 National Origins Act and the 1965 Immigration Act), the vast majority of these demographic gains came from an increased national birthrate. By 1964, Brands reports, four out of every ten Americans were Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964). The question for discerning students is how did all of these new children affect what Brands labels the “child-based culture” of the 1950s? One way to answer that question is by pointing to various trends in television, entertainment, music, sports, and other aspects of an emerging mass culture. But how much of this was a by-product of demographics or of new technologies remains an issue worth discussing.

Suburbs

The 1950s certainly marked an era of post-war industrial supremacy, rising consumerism, interstate highways, and general stability for American capitalism, but also the period showed signs of social strain as a new suburban-oriented and service-based economy developed. Post-war suburbs like the various Levitttowns offered both a model and a cautionary tale of the new age.

“When I was younger my dad did most of the talking and conversations were more solemn but when we moved out to the suburbs my mom definitely had more to say. I think working had given her the confidence to feel like she could contribute something more to the conversation.” [16] The television was a source of information for those conversations, “My mom would always tell us about the latest and greatest soap or new product that she saw on TV that would somehow greatly improve our lives!” [17]

Discussion Question

How would different types of post-war ideological movements characterize the rise of the suburbs? Consider examples such as conservatives, New Deal liberals, libertarians, and communists.

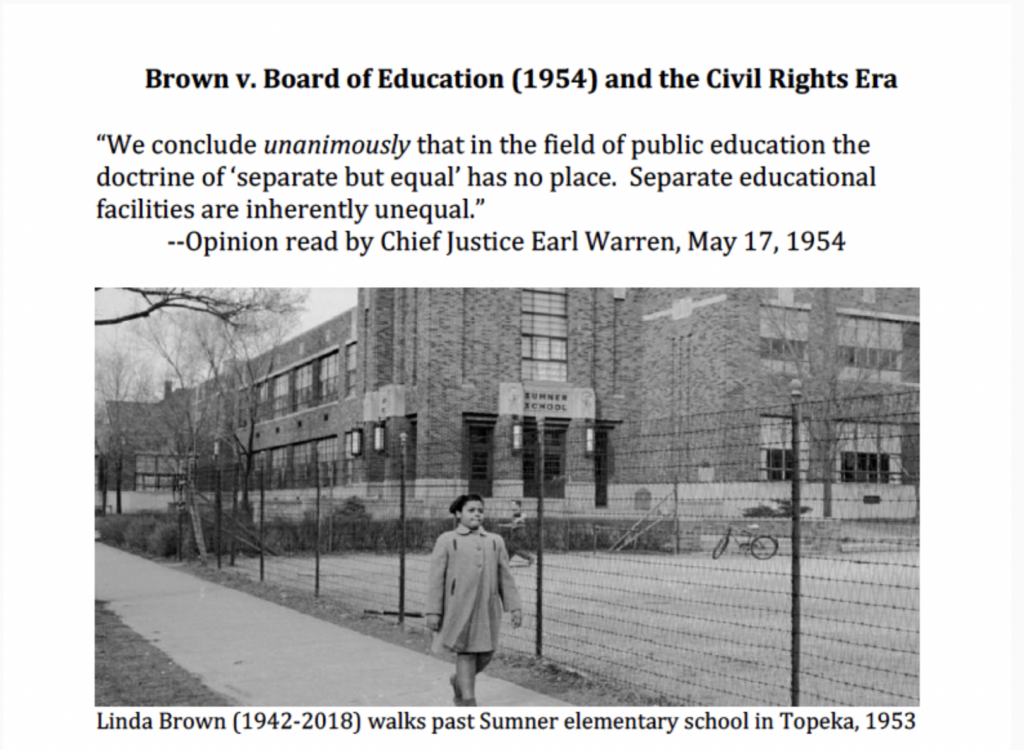

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

Elizabeth Eckford (pictured above) recalls her experiences as part of the Little Rock Nine

To learn more and to read a transcript of Eckford’s recollections, visit Facing History & Ourselves

Evolving Cold War

Many historians, including Brands, also find a revealing linkage between the domestic civil rights movement and the international Cold War. In particular, during the late 1950s and early 1960s, the struggle to contain communism seemed to migrate toward what was increasingly called the “Third World,” as American policymakers sought (often unsuccessfully) to influence events in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Thus, questions of race and geopolitical strategy often overlapped. Regardless of the regional challenge of the moment, however, leading the globalized Cold War proved to be an enormous burden for American policymakers. Brands ends his sprawling chapter on the 1950s by quoting from President Dwight Eisenhower’s now-famous farewell address (January 1961), which invoked a warning about the rising “military-industrial complex.” Yet this warning, however “sobering” in Brands’s words, was complicated, because Eisenhower, the former general and sometimes belligerent commander-in-chief, was by no means prepared to stand down in the global fight against what he termed in that speech a “hostile ideology … ruthless in purpose and insidious in method.” Clearly, whatever had been so golden about 1950s was also competing against many ominous shadows.