How did Progressives differ from Populists?

American Yawp, Chapter 20: The Progressive Era

- I. Introduction

- II. Mobilizing for Reform

- III. Women’s Movements

- IV. Targeting the Trusts

- V. Progressive Environmentalism

- VI. Jim Crow and African American Life

- VII. Conclusion

- VIII. Primary Sources

- IX. Reference Material

Image Gateway

Discussion Questions

- How might some Americans of that era, male or female, perceive this type of parade down Fifth Avenue on a Saturday afternoon to be dangerously provocative?

- Can you put the mobilization of suffrage parades, like this one by Harriot Stanton Blatch in New York City in 1912 into the context of other political rights struggles from the late nineteenth or early twentieth century?

Overview

“Widespread dissatisfaction with new trends in American society spurred the Progressive Era, named for the various progressive movements that attracted various constituencies around various reforms. Americans had many different ideas about how the country’s development should be managed and whose interests required the greatest protection. Reformers sought to clean up politics; Black Americans continued their long struggle for civil rights; women demanded the vote with greater intensity while also demanding a more equal role in society at large; and workers demanded higher wages, safer workplaces, and the union recognition that would guarantee these rights. Whatever their goals, reform became the word of the age, and the sum of their efforts, whatever their ultimate impact or original intentions, gave the era its name.” –Mary Anne Henderson, ed., Chapter 20: The Progressive Era, American Yawp [WEB]

Discussion Question

- How should historians distinguish late 19th-century populists from early 20th-century progressives?

Chinese Exclusion

During a 50-year period (from 1870-1920), over 25 million immigrants arrived in the US mostly from Southern and Eastern Europe (Yawp, chap. 19)

- First Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) (National Archives)

- Background on Wong Kim Ark, litigant in Supreme Court case (1898)

- Jonathan Katz, “Birth of a Birthright,” Politico (2018)

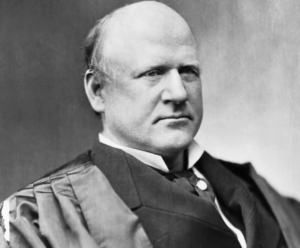

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896): “The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in power…. But in the view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” (Dissent by Justice John Marshall Harlan)

Wong Kim Ark (1898): “Generally speaking, I understand the subjects of the emperor of China—that ancient empire, with its history of thousands of years, and its unbroken continuity in belief, traditions, and government, in spite of revolutions and changes of dynasty—to be bound to him by every conception of duty and by every principle of their religion, of which filial piety is the first and greatest commandment; and formerly, perhaps still, their penal laws denounced the severest penalties on those who renounced their country and allegiance, and their abettors, and, in effect, held the relatives at home of Chinese in foreign lands as hostages for their loyalty. And, whatever concession may have been made by treaty in the direction of admitting the right of expatriation in some sense, they seem in the United States to have remained pilgrims and sojourners as all their fathers were.” —Fuller / Harlan Dissent in Wong Kim Ark (1898)

Women’s Movements

Election of 1912

Gifford Pinchot, former head of the US Forest Service, was actually the chief author of the Theodore Roosevelt’s 1910 “New Nationalism” speech, described above by the Wall Street Journal. Ex-president Roosevelt’s startling break with the Republican establishment helped lead to a four-way presidential contest in 1912. It also encouraged other precedents. Roosevelt was the first national candidate to openly endorse women’s suffrage. Jane Addams seconded his nomination at the Bull Moose convention, and over one million American women in six different western states were eligible to participate in this ground-breaking election.