I have never found census records to be particularly emotional. Names, numbers, and dates are supposed to objective things. When I began this assignment, I expected it to be interesting, but hardly emotional. By the end of my research, I had been proven wrong. Henry Spradley, my subject of study, has become more than just a name and a set of numbers. Through census records, marriage and death certificates, and the quickly growing family tree I have constructed, I discovered respect and admiration for Spradley’s family, a family I will never meet.

As with many subjects of historical research, I am far from being the first person to research his family, so I began where others had left off. Cursory searches of Dickinson’s House Divided and the Dickinson and Slavery pages were fruitful. I found the work of Colin Macfarlane, a 2011 student of Professor Pinsker’s who had researched Henry Spradley’s life. I watched his engaging video and read over the many blog entries he created. Next, I skimmed the encyclopedic entries about him on the House Divided page, gaining the valuable basic information about Spradley that I could use later (birth date, death date, birthplace, and so forth.) My goal from this secondary source research was to gather key terms or facts in order to use the Ancestry database as effectively as possible. So, armed with a master document of all the information I found, and most importantly, the primary sources these articles cited, I was ready for my next step.

One of the most impactful skills I learned using Ancestry was the art of narrowing my search requests down. Searching “Henry Spradley” without any supplementary information brought up thousands of results, so I became adept at plugging in the necessary supplements. From my secondary research, I knew he was formerly enslaved and born in Winchester City, Virginia, so at the suggestion of Professor Pinsker, I turned to the 1850 U.S Federal Census Slave Schedules. I tried every possible description of Spradley I could think of, typed in his birth year, and found… nothing. Without knowing where in Winchester City he had lived or what his “owner,” for lack of a better term, was named, the slave schedules were simply too vast for my research. The earliest documents were the Civil War-era registration records of Spradley entering the Union army on July 1st, 1863.

I may have had a rocky start, but this find propelled me forward. I immediately took notice of Spradley’s marital status – married. I knew Spradley had freed himself from slavery and escaped to Pennsylvania, thanks to the secondary sources, so that meant this “marriage” couldn’t have been legal. I tucked this thought away for research at a later date.

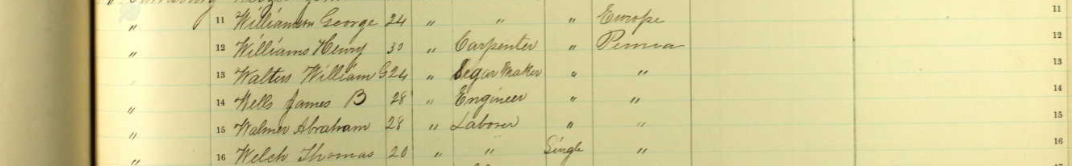

Another point to mention is Henry’s decision to use the last name Williams instead. I attribute this difference to the same reason as found by previous researchers of Spradley, like Colin McFarlane. It appears to be a choice Henry made to identify with Williams during the war as he had just freed himself from slavery. After the war, he used Spradley. The change in middle names later in his life in student publications like The Dickinsonian and the Microcosm, I believe, can be explained by typos or misunderstandings.

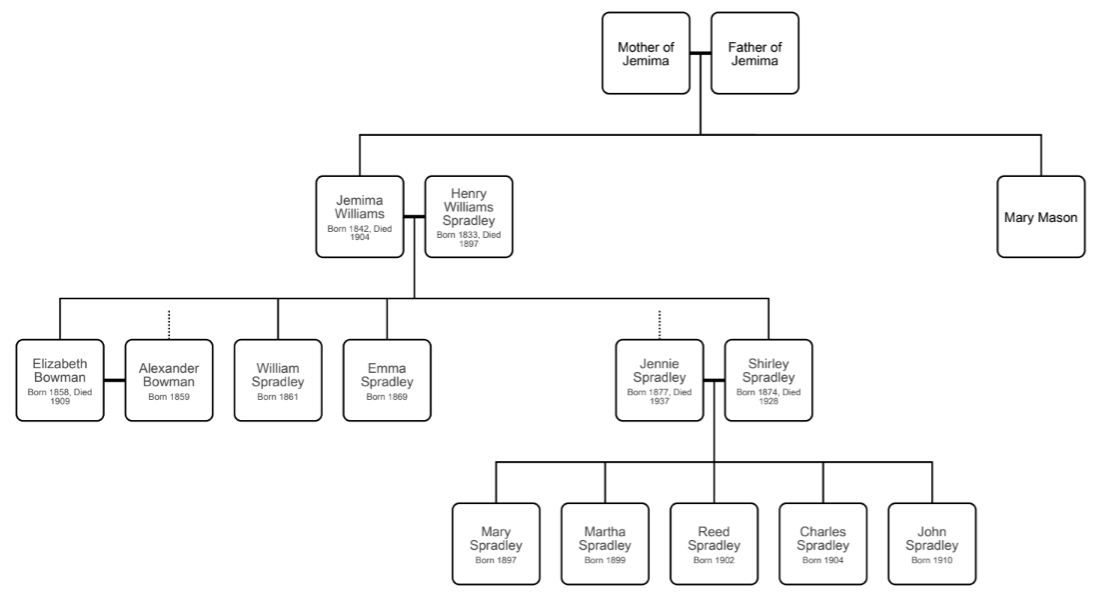

Next, I found the Pennsylvania Civil War Muster Rolls, where more information about his unit could be found. I was on a search for his family, however, so I moved on from his time served. His household appeared in the 1870 Federal Census and provided me with the first glance at his children (Elizabeth, Alexander, William, and Shirley) and wife (Jemima).

I took down the names and age estimates and began my family tree on a website called Family Echo.

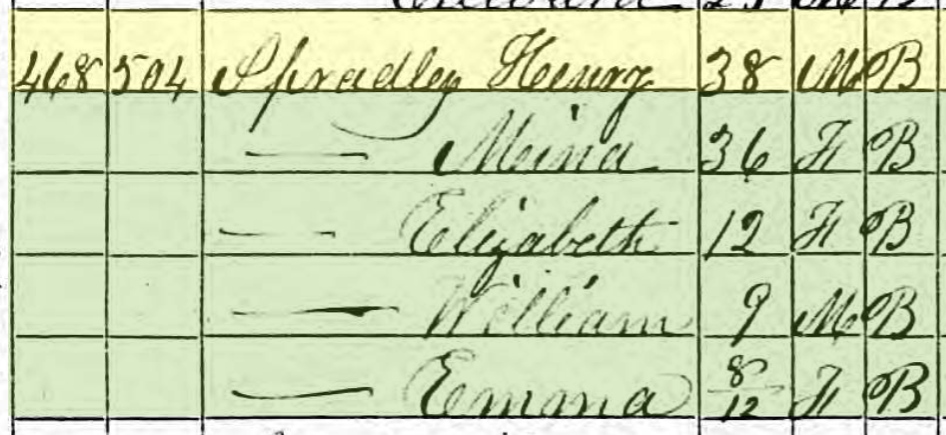

I jumped ahead to the 1880 Federal Census, where Spradley’s occupation was described as “laborer,” along with the first official mention of his son Shirley.

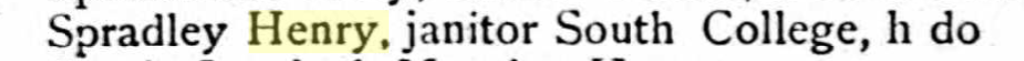

In an 1882 U.S City Directory, Henry Spradley’s address is listed as South College, and his job as “janitor.” He passed in 1897, as attested to by his death record. Satisfied with the overview I gained about Henry Spradley, I began what I can only call “the name game.”

To find more about their children, I moved on to Spradley’s wife, Jemima. Quickly, I discovered there was a host of names she was identified by – Mina, Minie, and Jennie. She was born around 1842, based on her age of 38 in the 1880 Federal Census.

Under the name Jennie in the 1900 United States Federal Census, I found her living with her then-married daughter, Elizabeth. I was excited to find three obituaries, dating her death to be in 1904, which had been unmentioned by any previous research. Unfortunately, behind a paywall, I couldn’t get access to them.

Next, I focused heavily on Elizabeth Spradley and her spouse, Alexander Bowman. Elizabeth, following the legacy of her mother, appeared as both Elizabeth and Lizzie. She was born around 1858, according to her age of 12 in the 1870 Federal Census, and lived with her family during the 1880 Census. She married Alexander Bowman in 1894 while Alexander was working as a dairyman. No children appeared in the record as far as I could tell. Elizabeth worked as a laundress in 1900, while she lived with her husband and mother. Alexander, like the Spradley family, was from Virginia. In 1900, he worked as a day laborer.

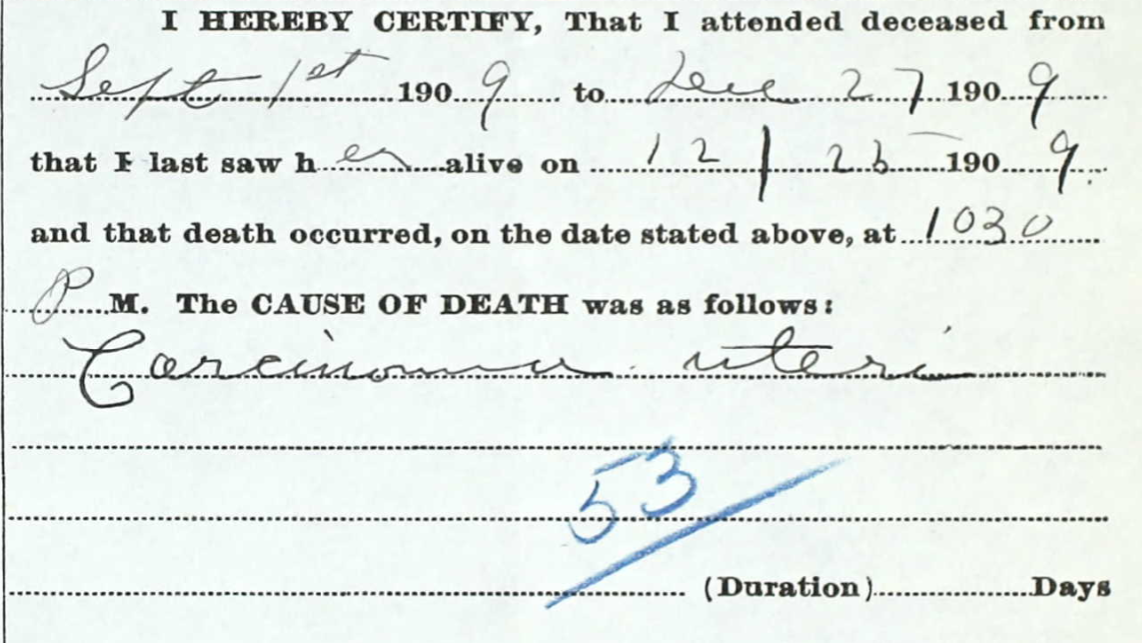

In 1909, Elizabeth passed away, and from what I could understand of the cause of death, it may have been cancer in her uterus. If I had more time, I would try harder to understand this entry and consult other people’s opinions.

After her death, I found Alexander living with his sister in the 1910 United States Federal Census. In 1920, he lived as a boarder in a house full of mostly children.

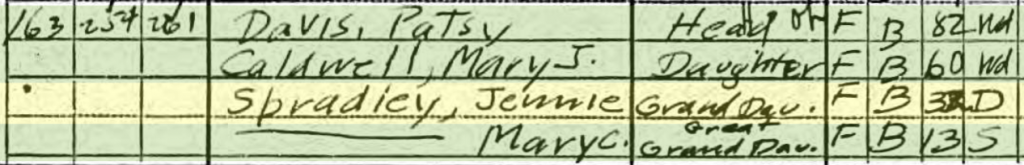

Shirley, Elizabeth’s brother, was born in 1874, according to the 1880 census. In 1896, he married Jennie Caldwell (yes, just like Jemima “Jennie” Spradley). In the 1900 census, Shirley and Jennie’s children, Mary and Martha are mentioned. The family lived with Patsy Davis, Jennie’s grandmother, and Mary, Jennie’s mother.

In 1910, Jennie identifies herself as divorced from Shirley, as well as mentioning her son Reed. Shirley enlists in the U.S army in 1917, but continues to refer to Jennie as his wife. In the 1920 census, Jennie and Shirley appear as still married. In 1928, Shirley passes. Jennie lives until 1937, working as a cook for 15 years in a hotel.

These were all only names and numbers, but through them, I followed an extended family as they moved, changed jobs, married, divorced?, and died. I found myself smiling when I calculated the dates of all the family’s marriages. Jemima and Henry both barely survived long enough to see Shirley and Elizabeth marry their spouses.

Lessons Learned and Loose Ends

Using the Ancestry database truly tested my ability to keep track of information effectively and efficiently to maximize my findings. Conflicting dates and names tripped me up, but by keeping detailed notes helped me power through. Though I was satisfied with the family tree I was able to construct, there remain some intriguing loose ends I hope to research in the future:

- the life of Alexander Bowman, especially as related to Dickinson College

- the remaining children of Henry and Jemima – William and Emma

- the marriage of Jennie and Shirley Spradley

Dr Barbara spradley king Mclaughlin

wow thank you so much on my 80th birthday this is the best gift I could receive information on my family tree I have travel many places looking for information on my family tree and call my self the historian I knew about Henry but not his family.i am thankful for your research. thank you Barbara spradley king Mclaughlin