In the first part of this research project I was challenged to conduct my own research and find primary sources using the Dickinson College Achieves. In that time, I was able to identify two students, William Laws Cannon and John Henry Grabill, who I believe will be the subject of my final project and primary sources concerning the two members of the class of 1860. Coming out of that assignment I was pretty confident in the research I was able to accomplish and felt as thou I learned valuable skills concerning research in archives. The next step of this project, is to identify newspapers that are related to our assigned class year of specific or “explore stories of students from their assigned class.”

In my previous part I mentioned that I was able to find John Grabill’s journal from the civil war from an online source, on the website it mentions that the journal was printed in the Shenandoah Herald, a newspaper that Grabill was the editor of later in his life. The journal was split up in three parts and printed the three consecutive issues spanning from January 8,15, and the 22 of 1909. Going into this second assignment focusing on newspapers I knew I wanted to find either digital or microfilm versions of the original newspapers the diary appeared in. Considering there was a requirement that we had to identify at least one microfilm that is relevant to our research I wanted to try and find a microfilm for the Shenandoah Herald from with these three issues on them. Unfortunately, I was unable to find microfilm for the Shenandoah Herald in either the Dickinson College microfilm collection or the Cumberland County Historical Society microfilm collection. After I realized I was not going to be able to find microfilm for the Shenandoah Herald, I decided that I should turn to digital databases in order to find these three specific issues.

website it mentions that the journal was printed in the Shenandoah Herald, a newspaper that Grabill was the editor of later in his life. The journal was split up in three parts and printed the three consecutive issues spanning from January 8,15, and the 22 of 1909. Going into this second assignment focusing on newspapers I knew I wanted to find either digital or microfilm versions of the original newspapers the diary appeared in. Considering there was a requirement that we had to identify at least one microfilm that is relevant to our research I wanted to try and find a microfilm for the Shenandoah Herald from with these three issues on them. Unfortunately, I was unable to find microfilm for the Shenandoah Herald in either the Dickinson College microfilm collection or the Cumberland County Historical Society microfilm collection. After I realized I was not going to be able to find microfilm for the Shenandoah Herald, I decided that I should turn to digital databases in order to find these three specific issues.

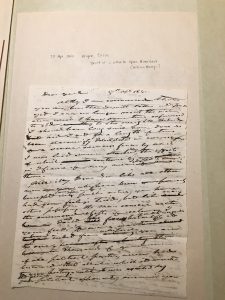

As Shenandoah is located in Virginia I decided to find  an archival database focused on Virginia. I was able to identify that the Library of Virginia had a digital archive of Virginia newspapers, available online. Using this website, I was able to find digital copies of all three copies the Shenandoah Herald that Grabill’s diary was printed in. The first issue that Grabill’s journal appeared in was January 8th, 1909. The journal appeared in the fourth column on the front page. This first part of the diary explains how Grabill found his old diary, presumably sometime in 1908 and decided to publish it in his newspaper. This part of the diary contains Grabill’s account of his time in the Stonewall Brigade, during the start of the civil war. With this issue I also decided to double

an archival database focused on Virginia. I was able to identify that the Library of Virginia had a digital archive of Virginia newspapers, available online. Using this website, I was able to find digital copies of all three copies the Shenandoah Herald that Grabill’s diary was printed in. The first issue that Grabill’s journal appeared in was January 8th, 1909. The journal appeared in the fourth column on the front page. This first part of the diary explains how Grabill found his old diary, presumably sometime in 1908 and decided to publish it in his newspaper. This part of the diary contains Grabill’s account of his time in the Stonewall Brigade, during the start of the civil war. With this issue I also decided to double  check that John Grabill was the editor of the newspaper at the time and to no surprise I found his name on the second page of the paper as the editor. Unless there was another John Grabill in Virginia who also published a newspaper, I found my guy. The following two issues of Shenandoah Herald contained the other two thirds of Grabill’s diary, both of which appeared on the front page of the issue.

check that John Grabill was the editor of the newspaper at the time and to no surprise I found his name on the second page of the paper as the editor. Unless there was another John Grabill in Virginia who also published a newspaper, I found my guy. The following two issues of Shenandoah Herald contained the other two thirds of Grabill’s diary, both of which appeared on the front page of the issue.

To this point in my research I was able to find the three issues of the Shenandoah Herald that I sought out to find, but I was unable to find a microfilm that was relevant to my research. I knew I had to find at least one article on microfilm, so I brainstormed possible topics I could attempt to find on microfilm. I decided I should skim through Grabill’s journal to find an event I could find on microfilm. On the entry of July 21, 1861 he recounts his view of the battle of Manassas, or more commonly known as Bull Run. As Bull Run is one of the most well-known battles of the Civil War, I decided that I would try to find newspaper articles covering the battle and see how they reported on the battle compared to Grabill’s recount on the civil war.

I started with trying to find an article covering the battle in the New York Times. (ViewScan_0000)I went to the Dickinson College library’s collection of microfilm and found the reel of the Times spanning from July-September 1861. I loaded the reel in to the microfilm readers and skimmed through until I found an issue printed approximately around the time of Bull Run. I was able to find an article covering Bull Run in the July 21, 1861 issues of the Times. The article entitled, The Fight at Bull’s Run, gives a brief account of both armies and their positions. As the article was printed prior to the end of the battle, the actual result was not encompassed in the article. As the article did not talk about the Union defeat, I once again spewed through microfilm attempting to find another article that did.

I eventually found an article in the Carlisle Herald. On the reel spanning from April 26, 1861 to September 28, 1866 I identified an article printed in the July 26 issue of the paper. A report with the date of July 22, 1861 covers the Confederate victory of Bull Run and the disorganized retreat of Union forces. The report has the heading of “Terrible Battle” and “3,000 Killed!” (ViewScan_0002) I found that this particular report and the prior report in the Times, were simply just reporting the facts of the battle. Compared to Grabill’s recount of the battle who was focused on his firsthand account of the events that took place.

While this focus on newspapers was the goal of this assignment, I found that the focus was a natural fit for me. In my previous research I found that Grabill printed the journal he used during the Civil War, in the newspaper he ran later in life. Using these newspaper records I have further fleshed out his journal for my larger project and learned how to use microfilm to me advantage.