The Process

This project is my first experience with archival research and I didn’t know where to begin. Luckily, Jim Gerencser and Malinda Triller Doran at the Dickinson College Archives had selected a document from our class year to examine. I received the anniversary address of the Belles Lettres Society in 1862. It was delivered by Martin Christian Herman, who coincidentally was one of the class members that I looked at in depth during my first research journal entry.

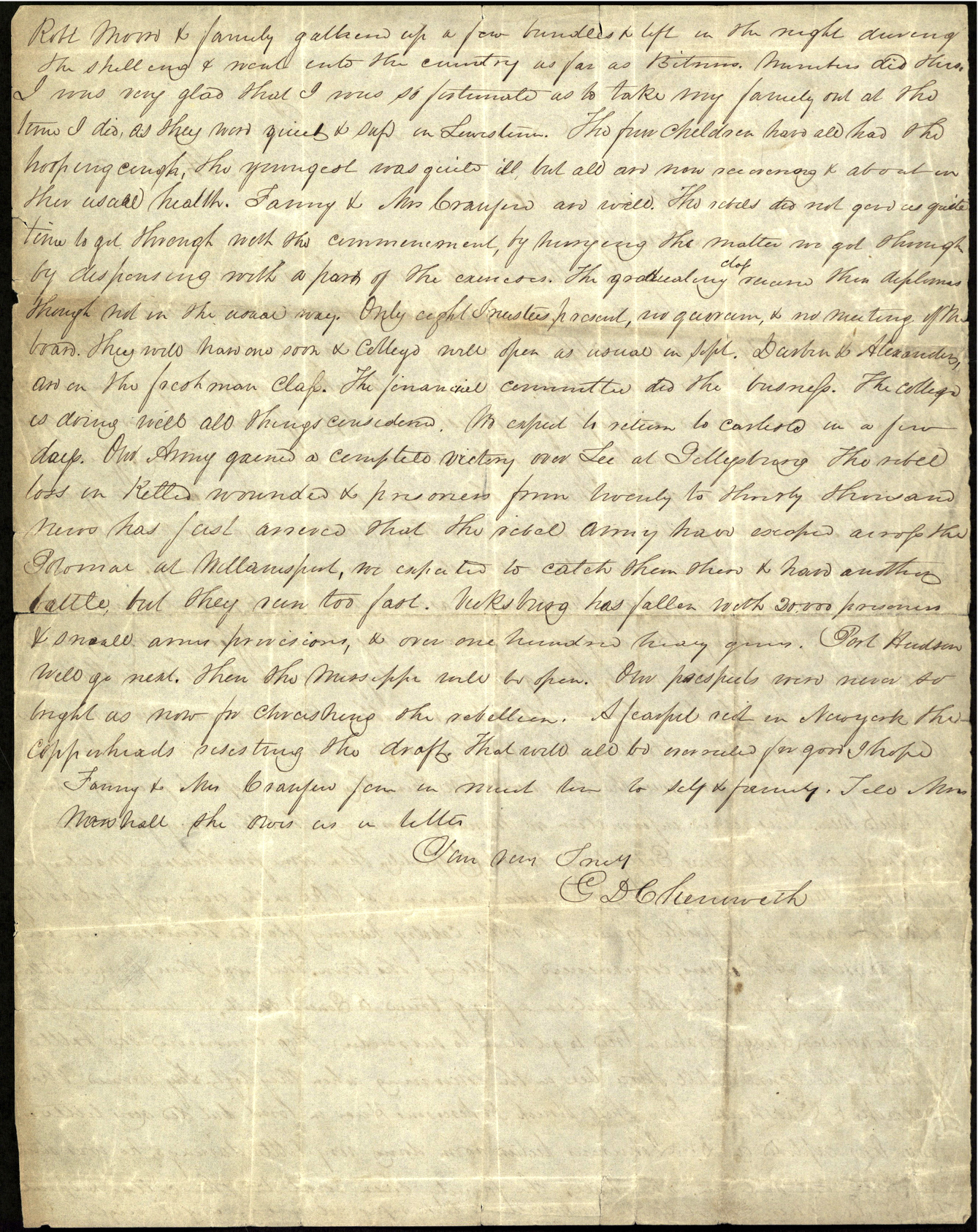

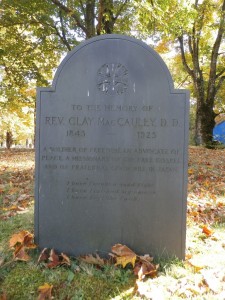

Belles Lettres Anniversary Address

The inside cover of the anniversary address of the Belles Lettres society in 1862. Document property of Dickinson College Archives.

This was the first time I have handled a historical document. The pamphlet was in good condition. From this document, one can learn about the writing style of the time period and what life at Dickinson was like. The document hints at a rivalry between the Belles Lettres and the Union Philosophical Society, the two literary societies at Dickinson.

The purpose of the item is to showcase the Belles Lettres literary society, their accomplishments, and their intellectualism. It also intends to discuss the progress of America. It addresses members of the grammar school who are preparing to enter Dickinson College and it gives them advice. It also promotes the Belles Lettres literary society to incoming students. The final paragraph is a farewell to the members of the class of 1862.

The anniversary address was very interesting. However, there was much more research to be done so I went back to the archives to start my own research.

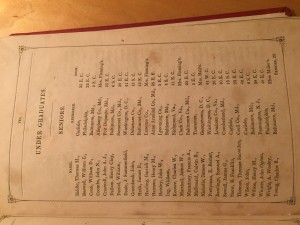

Dickinson College Catalog

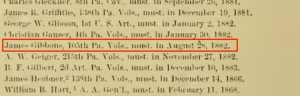

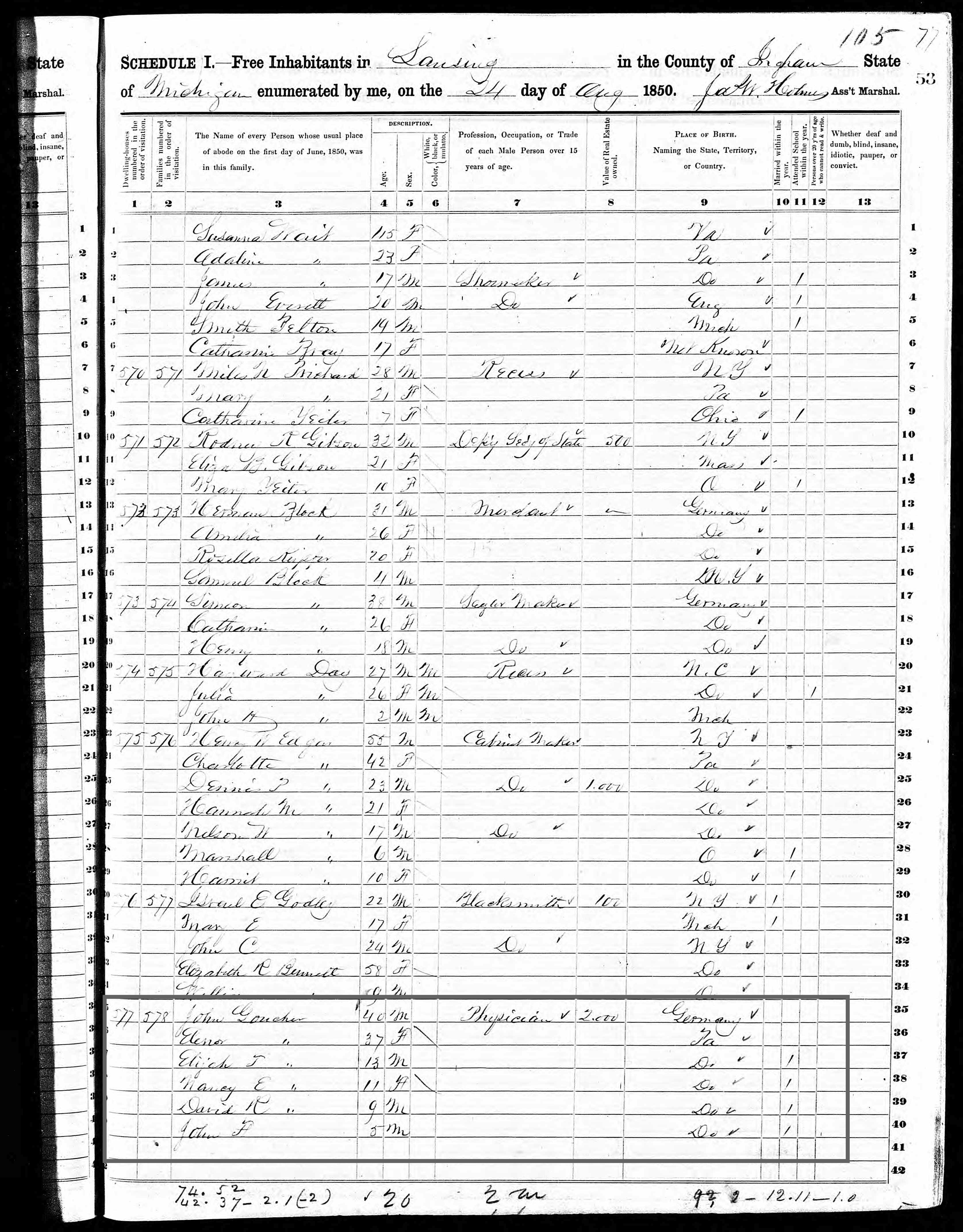

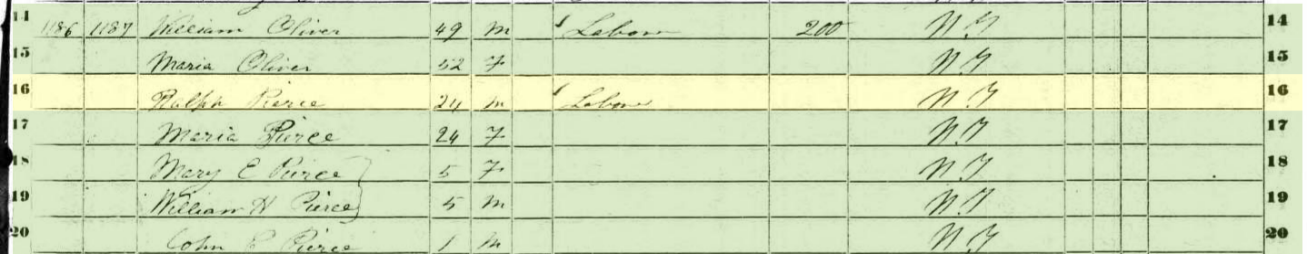

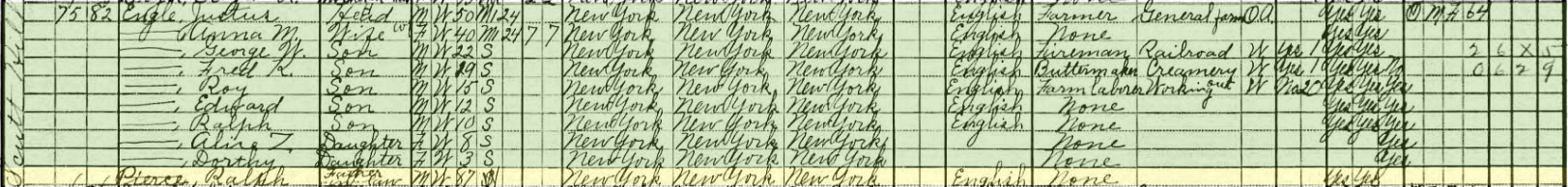

I began my archival search by searching for the Dickinson College catalog for 1862. The catalog is a very helpful tool because it details the curriculum of the time period, lists all the students by class year, and outlines the cost of tuition.The photo gallery below contains some important excerpts from the Dickinson College Catalog.

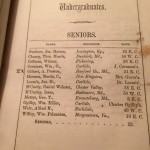

- List of the senior class of 1862.

- Excerpt from the Dickinson College Catalog. This page outlines some of the curriculum and provides insight on tuition.

- An excerpt from the Dickinson College Catalog. This page outlines the cost of tuition and certain student organizations on campus.

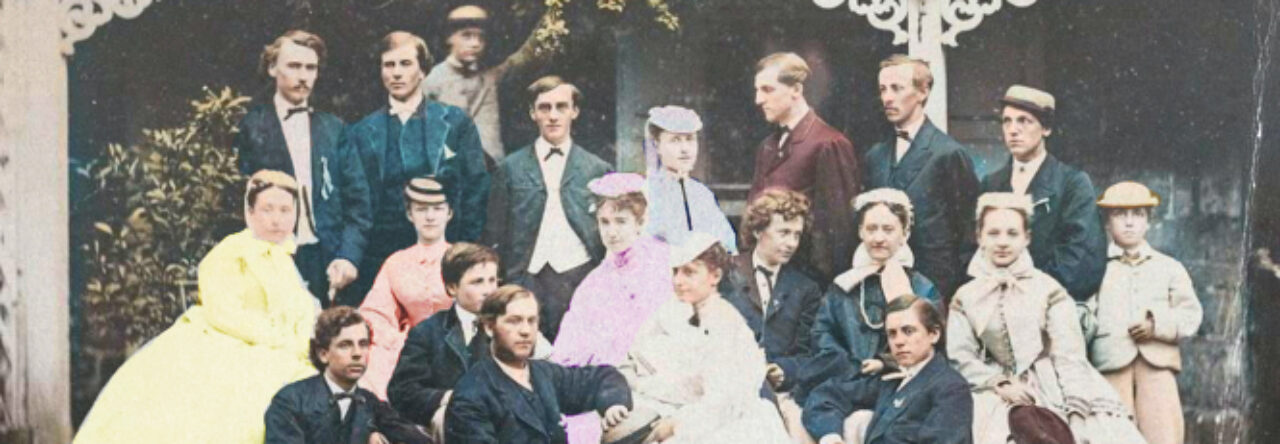

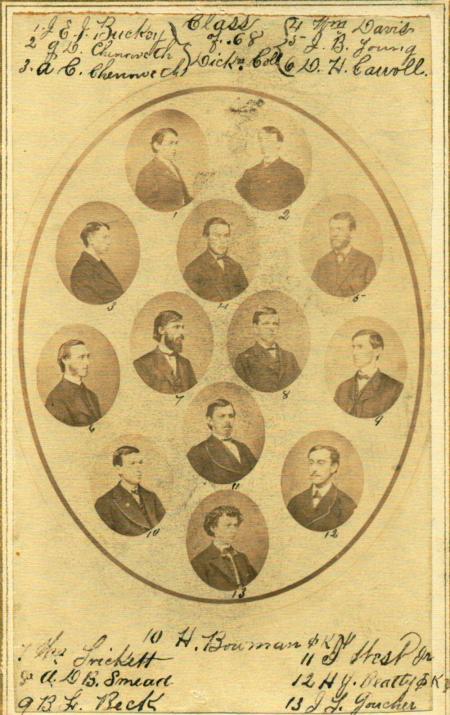

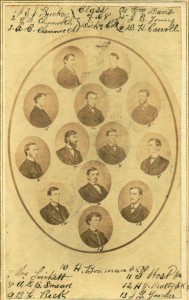

- The members of the Class of 1862 in their Junior year at Dickinson.

From the catalog, I could tell which members of the class of 1862 were at the college for their senior year compared to their junior year. The section on curriculum was particularly interesting. It outlined what topics the students studied, including religion, Latin, Greek, natural sciences, English, and German. The most shocking thing about the college catalog was the tuition. Fees and tuition for the entire year was $151, which would make any current college student very jealous. Overall, the college catalog does a great job of providing background on student life in 1862.

Images

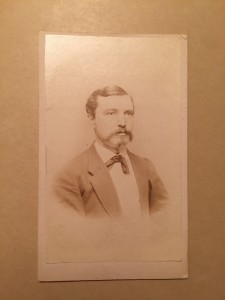

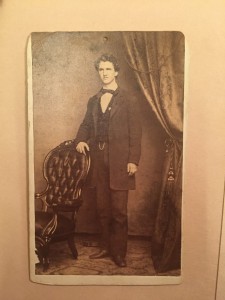

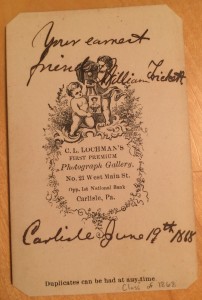

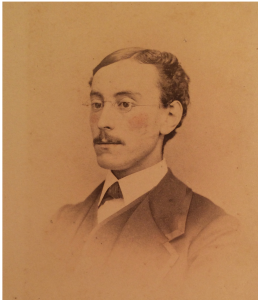

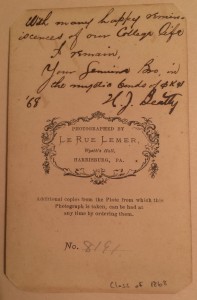

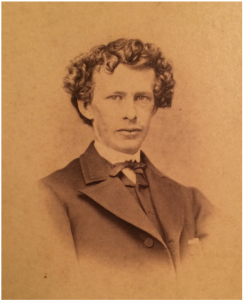

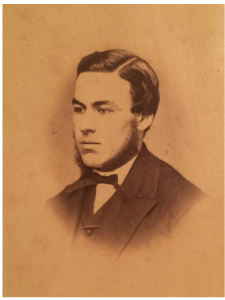

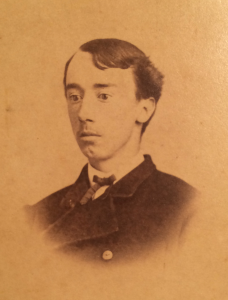

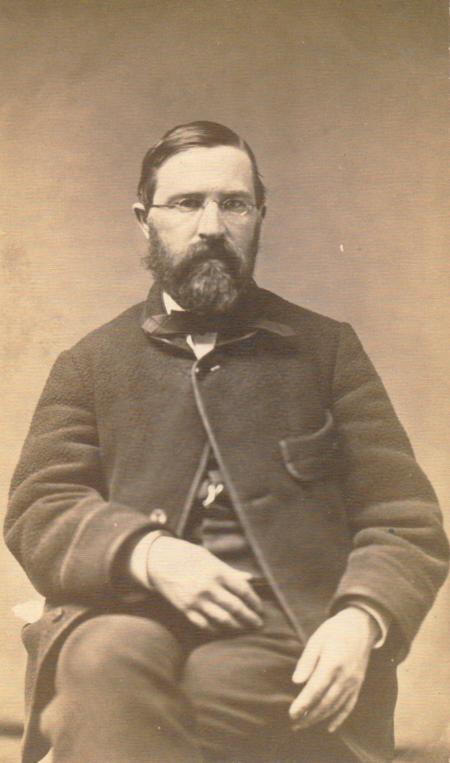

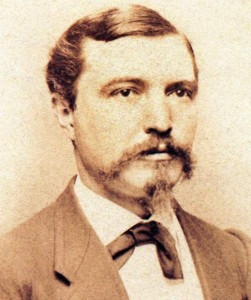

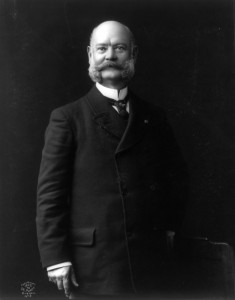

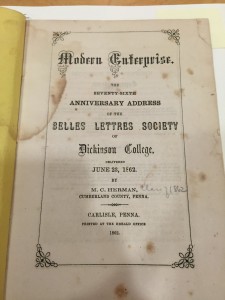

The next item I found in the Dickinson College archives was a carte de visite of Martin Christian Herman. I found this item thanks to the help of Frank Vitale, a member of Dickinson College archives staff.

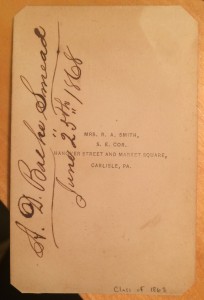

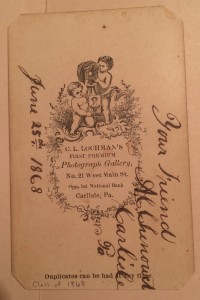

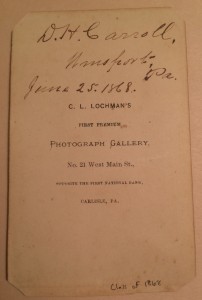

The back of the Martin Christian Herman carte de visite. Martin Christian Herman’s signature is on the back.

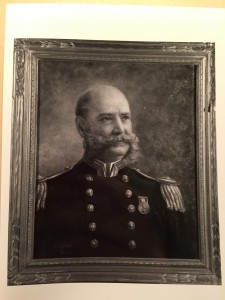

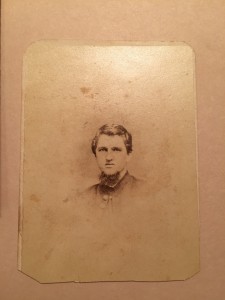

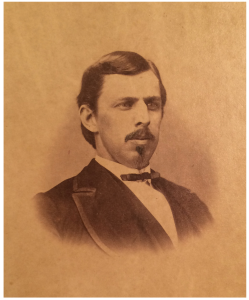

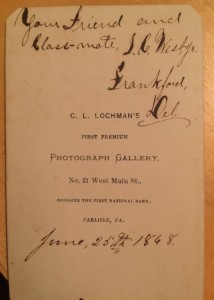

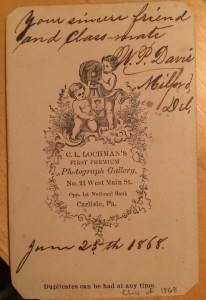

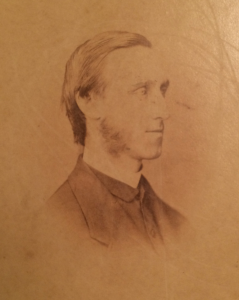

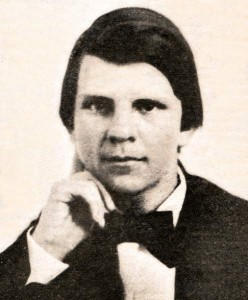

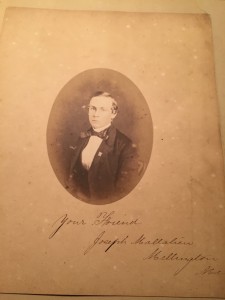

Frank Vitale Also helped me find images of two other members of the class of 1862, Benjamin Lamberton and Joseph Mallalieu. The two images are included below. My discovery of these images is all thanks to the staff at the Dickinson College Archives. Always make sure to reach out to the people who work in the archives because they know the archive better than anybody else and they will probably be able to find something that would otherwise be overlooked.

Image of Joseph Mallalieu, class of 1862. Handwriting reads: Your Friend, Joseph Mallalieu. Morllington (?) Md.

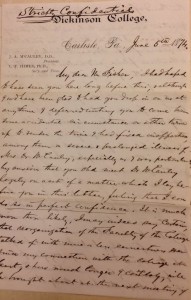

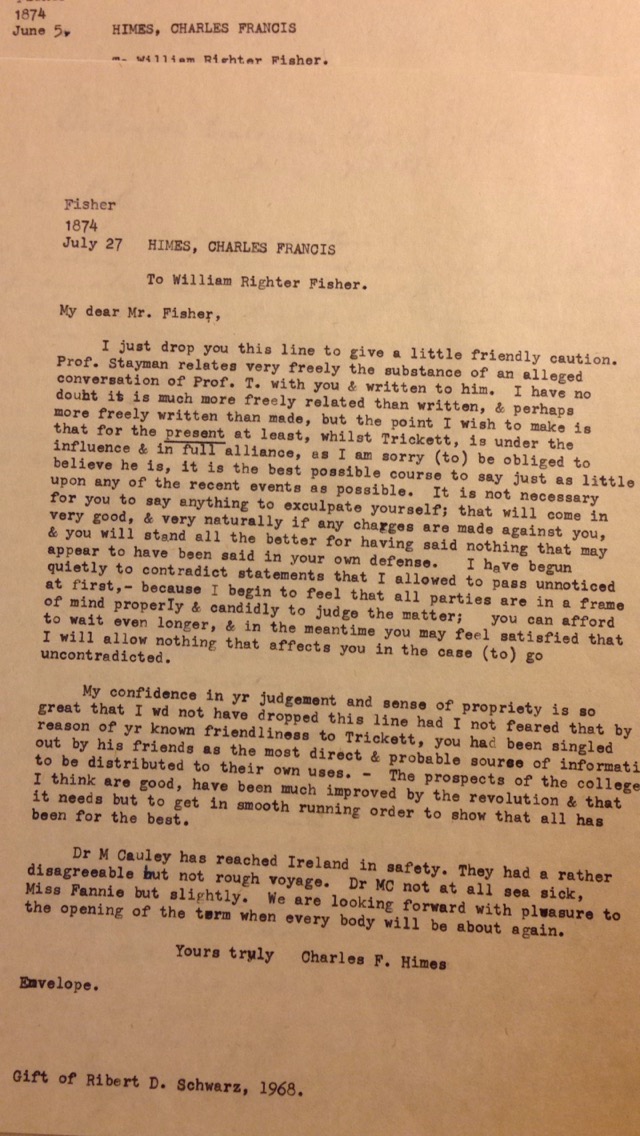

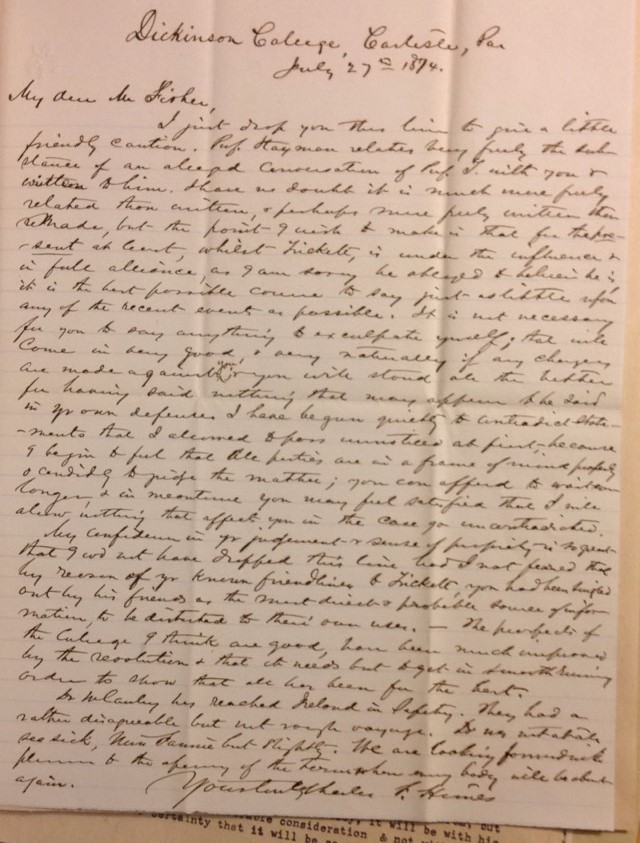

Card Catalog

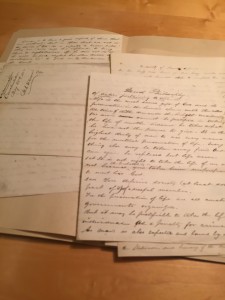

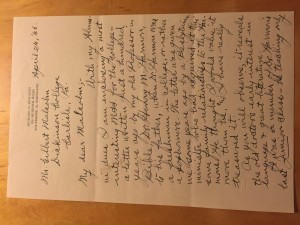

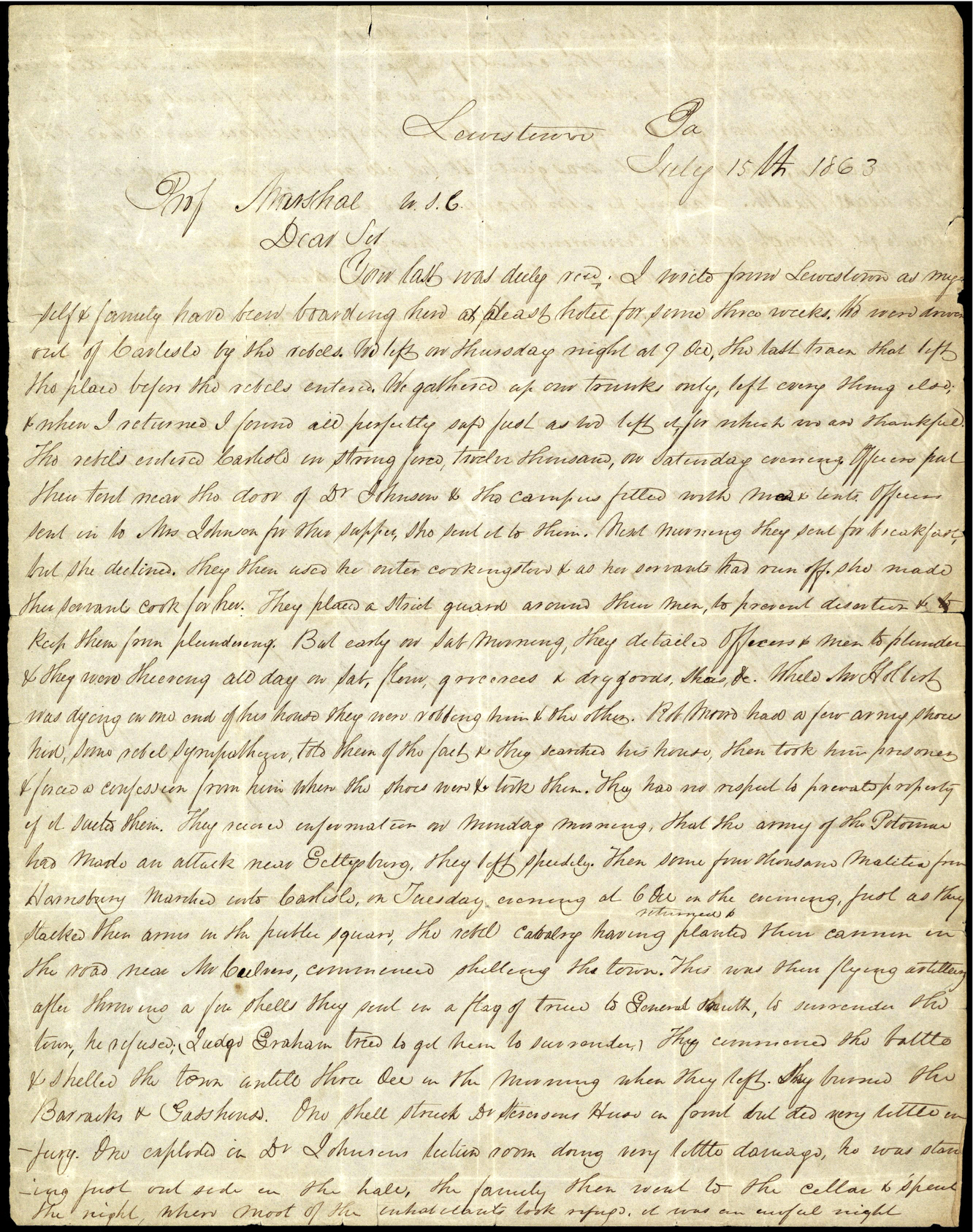

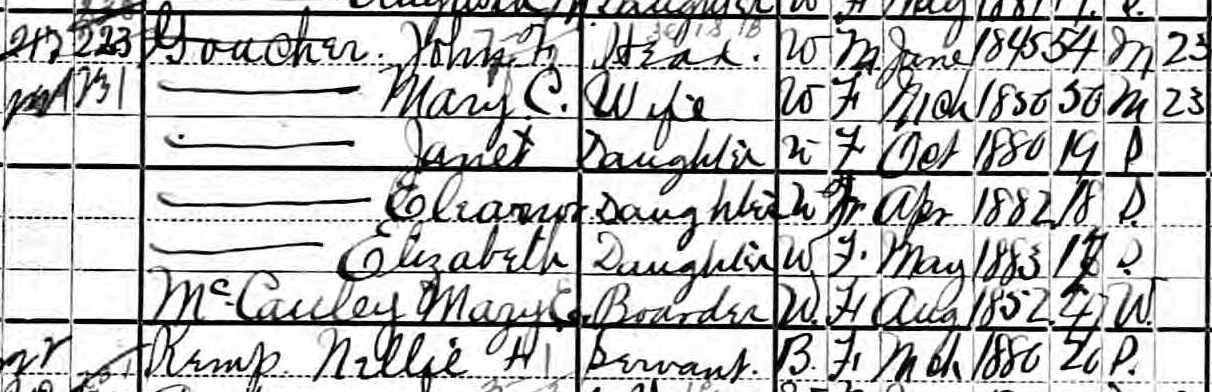

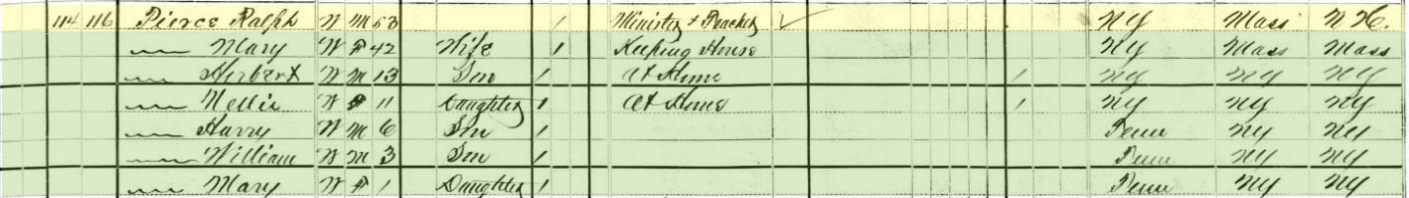

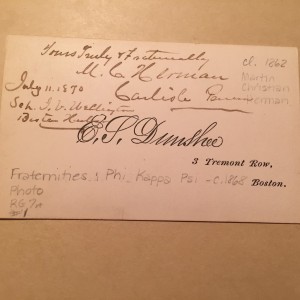

The next place I decided to look in the Dickinson College archives was the main card catalog. I started by looking up a few people from my class that particularly interested me. I started by searching for Benjamin Lamberton. Unfortunately, I did not find anything on him. I then searched for Clay McCauley. I was able to find two letters from his father, Isaac McCauley. They were addressed to Eli Slifer, the state treasurer at the time. The letters were written in script and were relatively hard to read. It briefly mentioned Clay McCauley but it was not the lead that I hoped it would be. It was a little disappointing considering how excited I was to find something on Clay McCauley. I definitely plan on going back to the archives and reading the letter again, in case I missed something amidst the 19th century handwriting.

One thing I did find of interest in the Isaac McCauley letter was the spelling of the name McCauley. As I discussed in my last research journal entry, there is a lot of confusion surrounding the spelling of Clay McCauley’s last name. In Isaac McCauley’s handwritten letter, he spells it as McCauley. This suggests that McCauley was the proper spelling of the name.

The next person I searched for in the card catalog was Martin Christian Herman. I found five compositions he wrote during his time at Dickinson. From these compositions and his anniversary address for the Belles Lettres society, it is clear that Herman was a skilled and prolific writer.

The compositions were in various conditions. One of the compositions had big stains on it so it was very hard to read. The compositions that I was able to read seemed to match the style of Herman’s writing for the anniversary address of the Belles Lettres society. The compositions demonstrate the expectations of students during the 1860s.

Overall, the card catalog in the Dickinson College archives is a very useful tool. It contains documents that are not yet listed on the Dickinson College Encyclopedia. No research trip to the archives would be complete without a visit to the card catalog.

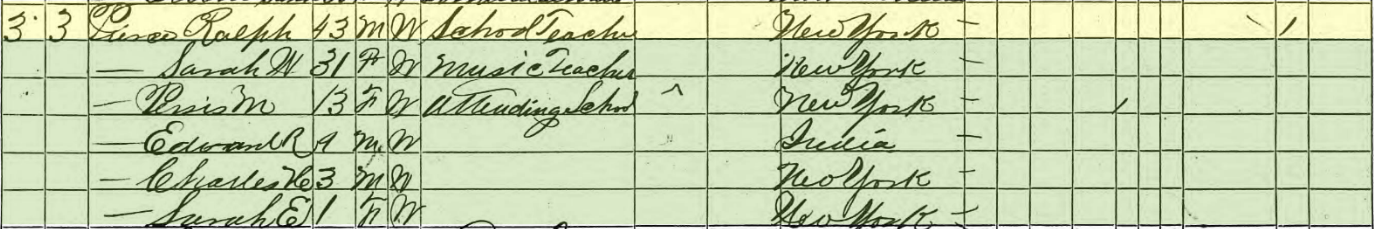

Collections Search

I turned my archival search to the Dickinson College special collections. The archives have extensive collections which are organized in binders of finding aids. I searched for who I believed to be the notable members of the class of 1862 in these binders. I did not find any of the people I searched. I immediately felt very frustrated. I decided to turn to the Dickinson College Archives website. They list all of their special collections, and you can search for specific collections. You can narrow down your search by time period. I narrowed my search to the time period of 1860-1879, and I sifted through the results until I came across the John Black, Jr. collection.

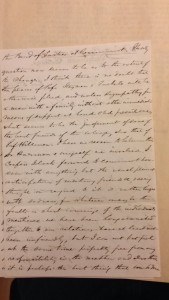

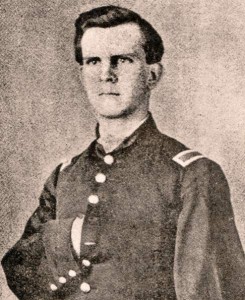

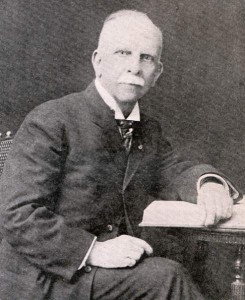

I was elated to find an entire collection on someone from the class of 1862. The John Black, Jr. collection contained many images, an artifact, various letters, a manuscript of family history, and a certificate of pharmacy.

I did not expect to find an entire collection on John Black, Jr. because he was not one of the members of the class of 1862 who I perceived to be the most interesting. The first leads you get in your research are not going to be your last. It is important to not close too many doors in regard to the subject of your research.

John Black, Jr. was a student at Dickinson College until 1860, when he was “honorably dismissed” from the college. He worked at a drug store until entering the Union Army. Black’s discharge letter is contained in the archives. Black spent most of his remaining years as a pharmacist. Black had two sons, who both died young. He also had a daughter and a step daughter. He was active in his community up until his death in 1915.

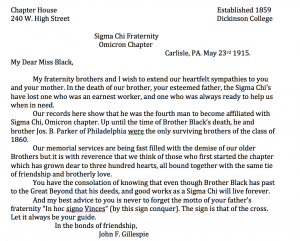

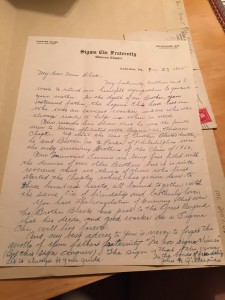

My favorite document in the John Black, Jr. collection was the letter that Sigma Chi Fraternity regarding the death of John Black, Jr. which I transcribed.

The letter is addressed to Alice Black, the daughter of John Black. It is from John Gillespie. It expresses his deep condolences for John Black’s death. I thought the letter was particularly interesting because it says that Black was the fourth man to become affiliated with Sigma Chi at Dickinson College. Even though this letter was written long after John Black’s time at Dickinson, it sheds light on John Black, Jr.’s life as a student at Dickinson and on the importance of greek organizations during that time period. It also suggests that John Black, Jr. was involved in Sigma Chi even after he left Dickinson College.

I must admit, John Black Jr. did not stand out to me during my initial research on the class of 1862. I would have never expected to find such an extensive collection on him. I was pleasantly surprised at this result. Sometimes research presents leads in unexpected places.

Reflection

I found this research assignment to be much harder than the first assignment. This was not research I could complete on my own schedule. The archives are only open at certain times during the week. My advice for anyone doing research in the archives is to manage your time. Make sure you know the hours that the archives is open and make sure that you make time for yourself to do research. Heading to the archives before class will be worth it.

Another piece of advice I have for anyone completing this assignment is try not to be discouraged. I hit many dead ends during my research. For instance, I spent a great deal of time looking at meeting minutes from different clubs and reading documents in Dickinson college president, Herman M. Johnson’s collection in the hopes of finding something relevant to my project. None of this ended up being fruitful but it is important to never give up.

Citations and Thanks

I would like to give special thanks to Jim Gerencser, Malinda Triller Doran, and Frank Vitale for helping me during my research at the archives.

Citation for transcribed material:

Gillespie, John, Carlisle to Black, Alice, 23 May 1841. , John Black, Jr. Papers, Archives and Special Collections, Carlisle, PA.