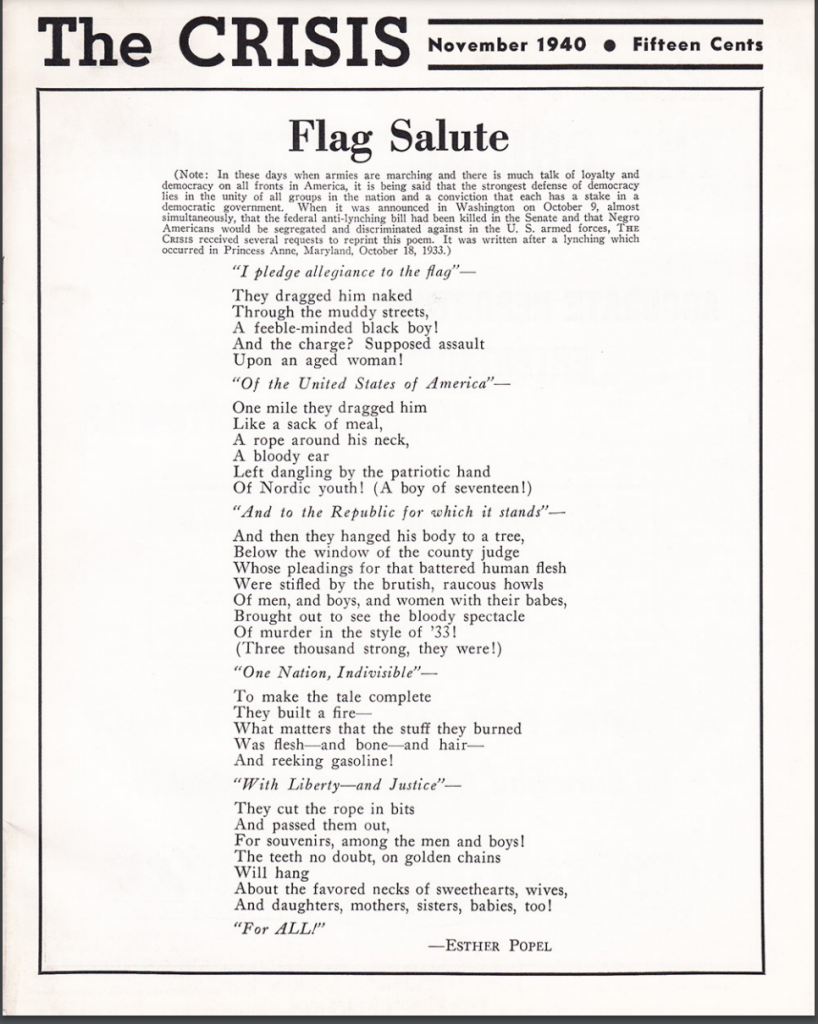

Esther Popel (1896-1958) became the first black female graduate of Dickinson College in 1919. She later married William Shaw and worked for most of her adult life as a teacher in Washington, DC. She had one daughter. Popel achieved her greatest national renown as poet and writer, often identified as an example of the dynamic “Harlem Renaissance” from the early twentieth century. The country’s leading civil rights organization, the National Association for the Advanced of Colored People (NAACP) often published Popel’s work in its magazine, The Crisis. Her best known poem, “Flag Salute,” actually appeared in The Crisis twice, once in 1934, following the lynching of a young black man in Maryland, and then again in November 1940, after the continued threat of filibuster in the US senate seemed to kill off any hopes of passage for a federal anti-lynching bill. Lynching refers to extra-judicial killings, intended as punishment but not authorized by law and usually targeting racial or religious minorities. The US senate did finally pass an anti-lynching measure in 2018, but there was no House action at that time. However, in March 2022, the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act finally became federal law.

Popel also wrote a short, fascinating memoir entitled, “Personal Adventures in Race Relations” (1948) that is available online through the Dickinson College Archives and which probably conveys her smart, witty but subtly combative personality as well as any source. To learn more about how students at Dickinson are engaging with the legacy of Esther Popel in their own lives, visit the Popel Shaw Center for Race & Ethnicity.

Passages from Personal Adventures in Race Relations (1948)

“The constant and soul-searing humiliation that is the outgrowth of the dangerously reactionary policies of prejudice and biracialism serves to undermine the faith of the Negro, and other minorities, in the very foundation of the democracy they are asked to defend. Tensions have reached the explosive stage, and intelligent action is needed if we are to prevent consequences that can be utterly disastrous. In an atomic age we need atomic understanding!” (p. 3)

“The Negro director of a Federal Housing Project in Chicago [Robert Taylor] was asked to find a place on his staff for a Japanese-American girl just out of a relocation center. She was seeking employment. When the director approached his colored office workers on the subject they all objected most strenuously. They didn’t want to work with a “Jap”. In order to change this feeling the director gave a long and stirring lecture to them on proper racial attitudes, until he finally succeeded in overcoming their objections. The Japanese-American girl came, and as the weeks passed she and the one girl in particular who had at first so bitterly opposed her employment became good friends. One day the latter was talking about the Nisei girl to her director. After expressing her affection for the new office worker she said: “You know, Mitsui is very glad she’s working here with us. She said she’d so much rather be here than with those Jews in the downtown office!” (p. 6-7)

“Encountered recently in a pre-Christmas crowd while [this black teacher] was on her way to do her Christmas shopping, she gave forth this amazing piece of evidence of the deep-seated, inner resentment which controls her life whether or not she realizes its import. These were her words as she joked about Christmas shopping: ‘I just love Christmas time, and Christmas shopping. It gives me a chance to get my arms full of bundles and go barging through the stores where I can bump into these old “crackers” and step on their toes and push them out of my way. And they can’t do or say anything about it because in a Christmas crowd nobody has to be bothered about being polite to them!’ Christmas Spirit in the 1940’s! This is as eloquent an indictment of racial proscription as one may cite. And the tragedy underlying it is significant also, for hers is not the only soul that has become warped in such fashion.” (p. 19)