Schrag’s Checklist of Non-Text Primary Sources (chap. 7)

- Numbers

- Maps

- Images

- Portraits

- Motion Pictures and Recordings

- Artifacts

- Buildings and Plans

- Places

Case study: The Scourged Back

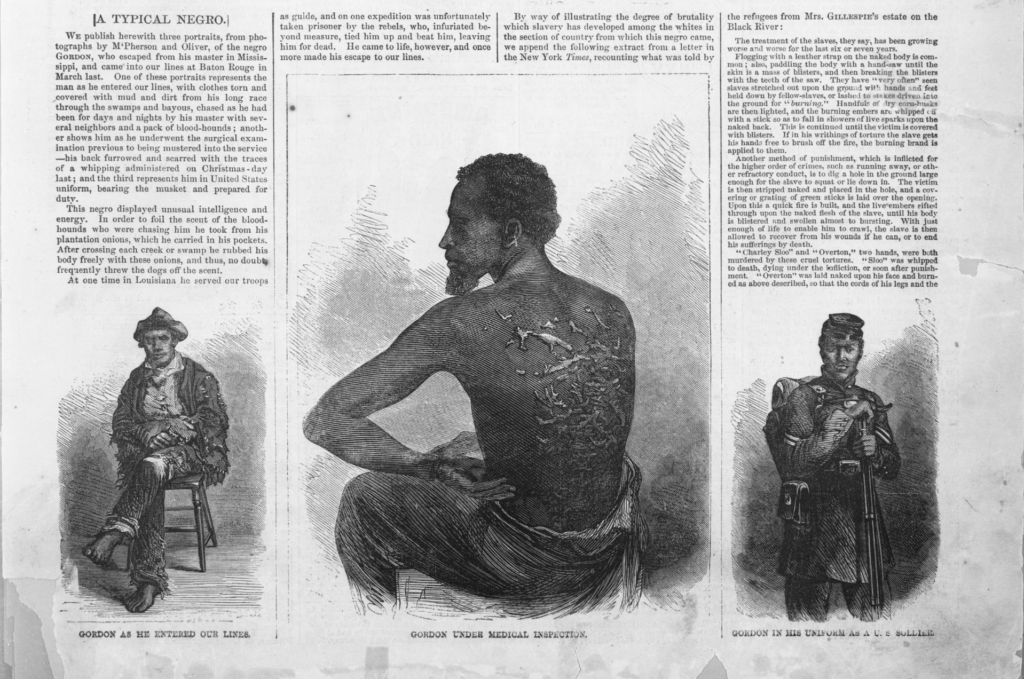

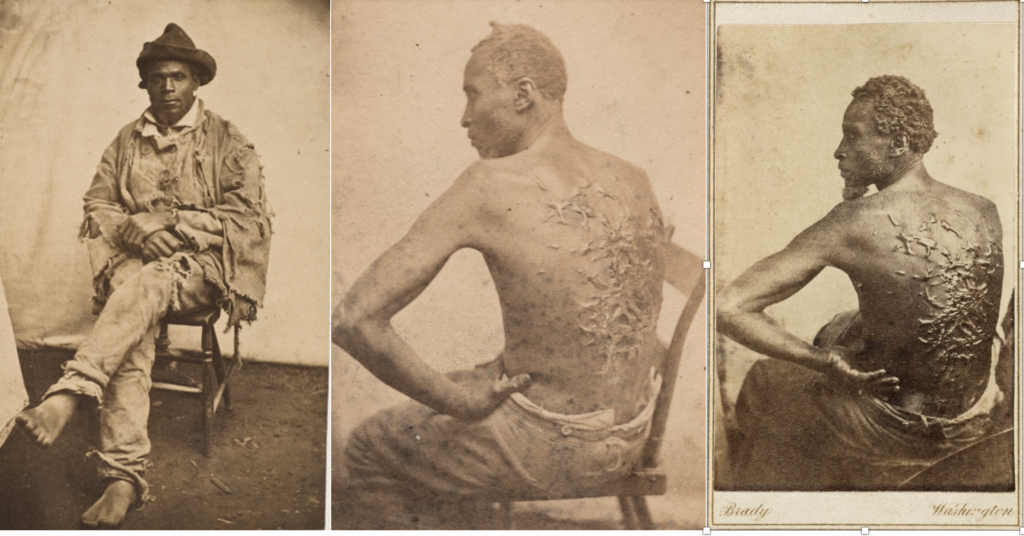

Photographic sources for Harper’s illustrations, taken behind Union lines in Louisiana, April 1863 (Library of Congress)

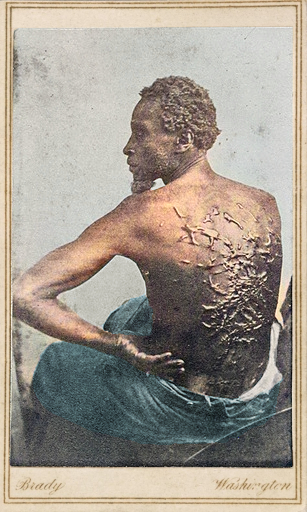

“Scourged Back” by William D. McPherson, Baton Rouge, 1863, colorized in 2023 using artificial intelligence (AI) programs

The Independent from New York, an antislavery periodical, first described the “Scourged Back” photographs on May 28, 1863, in an article that urged the likeness to be distributed widely as a “card-photograph” or carte de visite (CDV; see Brady version on far right above). The new editor, Theodore Tilton, wrote:

“This card-photograph should be multiplied by the hundred thousand, and scattered over the States. It tells the story in a way that even Mrs. Stowe cannot approach; because it tells the story to the eye.

You can read a reprint of that original May 28th article in The Liberator, June 19, 1863, which had just the week before begun selling the “Scourged Back” CDVs for 15 cents per card. That same week, William Lloyd Garrison, Jr. also provided his own reaction to the “Scourged Back” in a piece for his father’s newspaper on June 12, 1863. The editor’s son quoted a letter from a white surgeon in a black union regiment (First Louisiana) reporting that he had seen “hundreds” of such scourged backs among his men and that the image was important, because, “It is a lecture in itself.”

Especially following the publication on the illustrations in Harpers in July 1863, Southern and some Northern Democratic newspapers denied the authenticity of the story behind the scourged back images. The Southern Illustrated News wrote on July 25, 1863: “A more palpable falsehood was never published in any Yankee newspaper.”

Under the headline, “Poor Peter,” the New York Tribune provided a fuller description of the background behind the infamy of the “scourged back” images, explaining that there were two different, French-speaking “contrabands,” Peter (whipped back) and Gordon (ragged clothes), not a single transformed runaway, who appeared behind Union lines near Baton Rouge. The description, including a translation of an interview with Peter, appeared in an article from December 3, 1863.

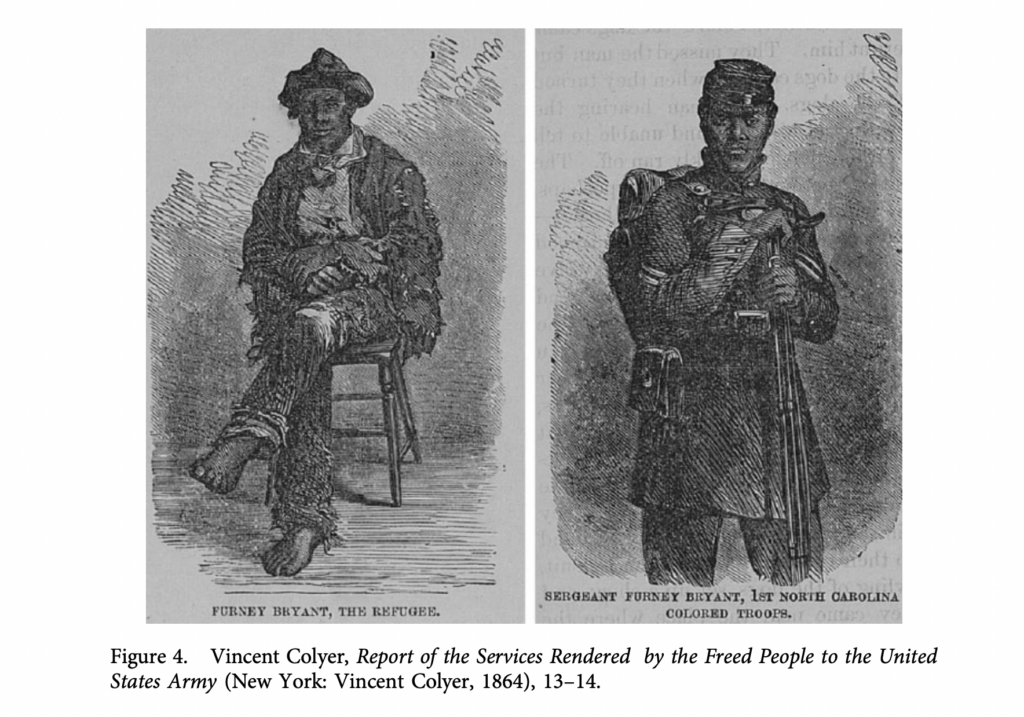

The best scholarly account of the “scourged back” image comes from David Silkenat, “‘A Typical Negro’: Gordon, Peter, Vincent Colyer, and the Story behind Slavery’s Most Famous Photograph,” American Nineteenth Century History 15 (2014): 169-86 (America: History & Life). Silkenat identifies the likely Harper’s illustrator and author of the “A Typical Negro” article as Vincent Colyer, showing how the artist and government agent re-used two of the images (the before & after illustrations) in a book about his experiences in North Carolina. In that volume, Colyer claimed the black soldier who had appeared in Union lines was a runaway named Furney Bryant. However, Silkenat doubts the veracity of this claim. He does seem more willing to accept the possibility that the December 1863 Tribune article distinguishing between “Peter” and “Gordon” was accurate, though even on this critical point, he lacks certainty.

“Emancipation” (2022)