If you cannot spark an interest in the first few sentences of a proposal, you may lose your chance. –Zachary Schrag, Princeton Guide to Historical Research, Chapter 13

Working to Scale

- “If you can state your most important findings in 180 seconds, you will also be able to state them in an 800-word op-ed, a 20-minute presentation, a 45-minute public lecture, a 10,000 -word article, and a 100,000-word book, the only difference being the level of detail, nuance, and evidence you can present.” (Chap. 13)

Know Your Ledes

- “An introduction to an analytical work must state a thesis. It may also include two additional parts. First, a lede –the journalist’s term for a short but provocative flash of narrative text … The second optional part is historiography, which highlights the novelty of the work’s findings.” (Chap. 13)

- Schrag’s thesis formula: “[Why] did [people] do/say/write [something surprising]? [Plausible alternative explanation], but in fact [better or more complete explanation.” (Chap. 13)

- SUMMARY: WHY people changed and HOW other historians missed it

- See also Methods Center handout on How to Write a Thesis Statement

Mastering Paragraphs

- From the Five-Paragraph Essay to the 22-paragraph term paper

- Why topic sentences matter

- Using section headings

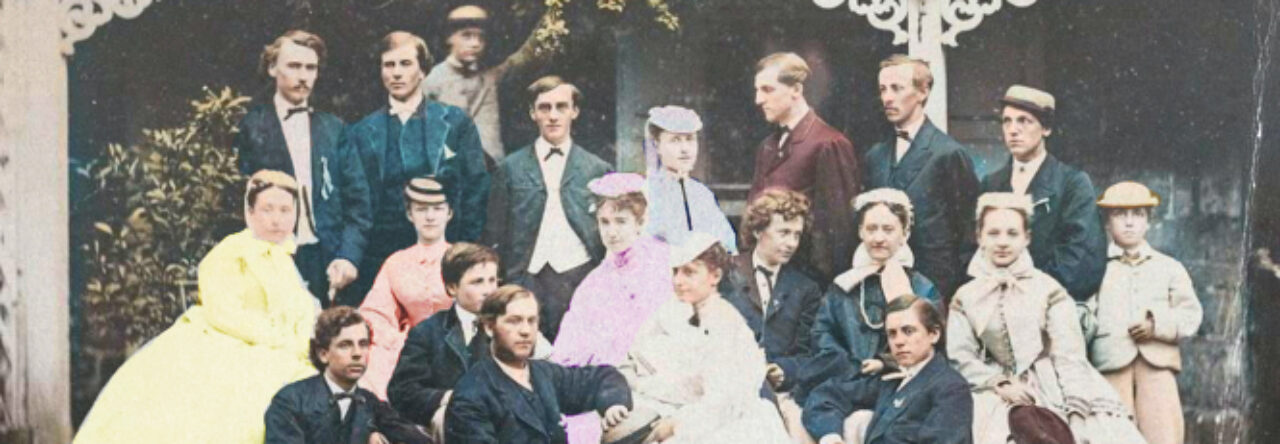

Characters

- “Strong protagonists make the best stories.” (Chap. 14)

- “devote the most time to trying to understand … villains” (Chap. 14)

- Witnesses!

- Always remember the dialectic: thesis, antithesis, synthesis

Sources

- “A historian is an alchemist who turns paper and ink into flesh and blood.” (Chap. 14)

Timelines

- “When in doubt, tell a story in chronological order.” (Chap. 14)