“Thus, the source of judicial review as Americans understand it today lay not in the idea of fundamental law or in written constitutions, but in the transformation of this written fundamental law into the kind of law that could be expounded and constructed in the ordinary court system.” –Gordon Wood, Power and Liberty, p. 139

“When the Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville visited America in the 1830s, he pointed out that lawyers had come to constitute whatever aristocracy America possessed, at least in the North. Through their influence on the judiciary, they tempered America’s turbulent and unruly majoritarian governments and promoted the rights of individuals and minorities. ‘The courts of justice,’ Tocqueville said, ‘are the visible organs by which the legal profession is enabled to control the democracy.’ It is still a shrewd judgment.” –Gordon Wood, Power and Liberty, p. 148

Timeline of Judicial Review

- 1770s // Colonial judges reviled by American patriots

- 1780s // Most state judges appointed by legislatures; no Confederation judges

- 1787 // Article III powers vest independent federal judiciary with life appointment

- 1788 // Hamilton argues for judges as representative of people in Federalist No. 78

- 1790s // Hamiltonians and Jeffersonians collide over constitutional questions

- 1803 // Chief Justice John Marshall in Marbury v. Madison establishes precedent of federal judicial review for a case involving the 1789 (not 1801) Judiciary Act

- 1800s and beyond // Federal judges gain authority to “say what the law is” (p. 141)

Discussion Questions

- How did frustrating experiences with state legislatures and various failed attempts to codify American law contribute to the movement for establishing a strong national judiciary in the 1787 constitution?

- How did applying doctrines of “common law” become controversial and partisan during the days of the early republic?

- What does the concept of “judicial review” mean and why was its development in American jurisprudence so uncertain and complicated?

Vocabulary of American Constitutionalism

- Common Law –precedents and interpretations (judge-made)

- Coverture (married women’s dependency)

- Fugitive slave recaption (return of mobile property)

- Sedition (Federalist judges vs. Jeffersonian Republicans)

- Statutory Law –legislation (Congressional and legislative)

- Constitutional Law –fundamental

- Challenges: American federalism (state, federal, territorial)

- Challenges: co-equal branches or judicial supremacy?

- Challenges: Original intent, original meaning, or original principles?

Article III

Section 1

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

Annotated resources via The Founders’ Constitution

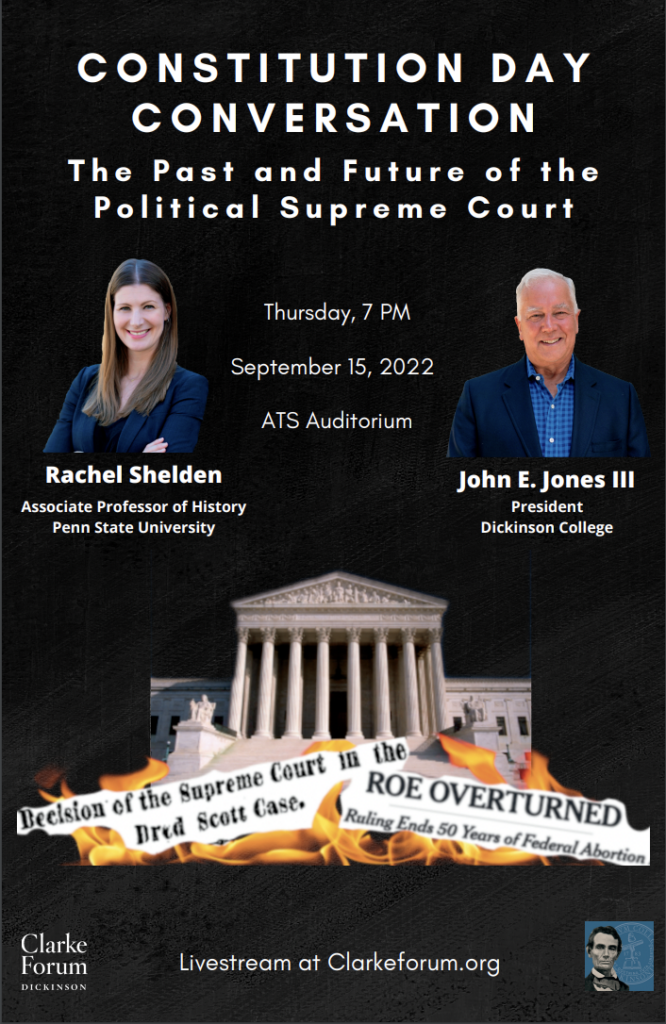

The Past and Future of the Political Supreme Court

“Today, the court has far more power to shape American life than it did in the 19th century.” –Rachel Shelden, Washington Post, May 7, 2022