The life of Wong Kim Ark exemplifies the shifting grounds on which birthright citizenship has been contested over the last 150 years. Newly discovered archival materials reveal that Wong and his family experienced firsthand, and at times shaped, the fluctuating relationship between immigration, citizenship, and access to civil and political rights.–Amanda Frost

- First Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) (National Archives)

- Background on Wong Kim Ark, litigant in Supreme Court case (1898)

- Jonathan Katz, “Birth of a Birthright,” Politico (2018)

Fourteenth Amendment (1866 / 1868) Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

ORIGINS: Civil Rights Act of 1866 SEC. 1: That all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States;

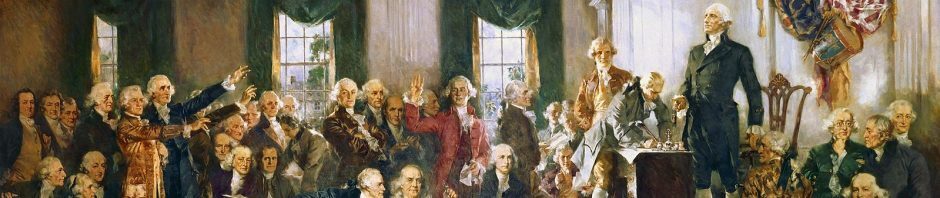

ORIGINS: Article IV of the US Constitution (1787): The Citizens of each State shall be

entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.

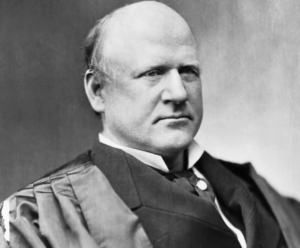

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896): “The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in power…. But in the view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” (Dissent by Justice John Marshall Harlan)

Wong Kim Ark (1898): “Generally speaking, I understand the subjects of the emperor of China—that ancient empire, with its history of thousands of years, and its unbroken continuity in belief, traditions, and government, in spite of revolutions and changes of dynasty—to be bound to him by every conception of duty and by every principle of their religion, of which filial piety is the first and greatest commandment; and formerly, perhaps still, their penal laws denounced the severest penalties on those who renounced their country and allegiance, and their abettors, and, in effect, held the relatives at home of Chinese in foreign lands as hostages for their loyalty. And, whatever concession may have been made by treaty in the direction of admitting the right of expatriation in some sense, they seem in the United States to have remained pilgrims and sojourners as all their fathers were.” —Fuller / Harlan Dissent in Wong Kim Ark (1898)

The decision in Wong Kim Ark was important, to be sure, but its primary effect was to shift the fight over birthright citizenship from the lofty GrecoRoman chambers of the federal courts to the drab administrative offices of immigration inspectors at ports of entry, where executive branch officials have nearly unfettered power to decide who is and is not an American. Likewise, birthright citizenship led both state and federal officials to erect new hurdles to proving citizenship—a prerequisite to exercising many civil and political rights, and in particular the right to vote. —Amanda Frost