As a remedy for the democratic ills of the 1780s, [the Constitution] fell short of the mark. Still, it was better than the Articles of Confederation, and Madison and Hamilton began working for its ratification by the states. Together with John Jay, they wrote under the pseudonym “Publius” eighty-five papers, published initially in newspaper between October 1787 and the summer of 1788 and later collected in book form as THE FEDERALIST. The essays were designed principally to convince New Yorkers to ratify the new document. Precisely because the issue of the Constitution’s republican character seemed so much in doubt, the authors spent a considerable amount of time describing just how republican the new government was. In the Constitution, wrote Madison in Federalist No. 10, ‘we behold a republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republicanism.’ –Gordon Wood, Power and Liberty, pp. 86-87

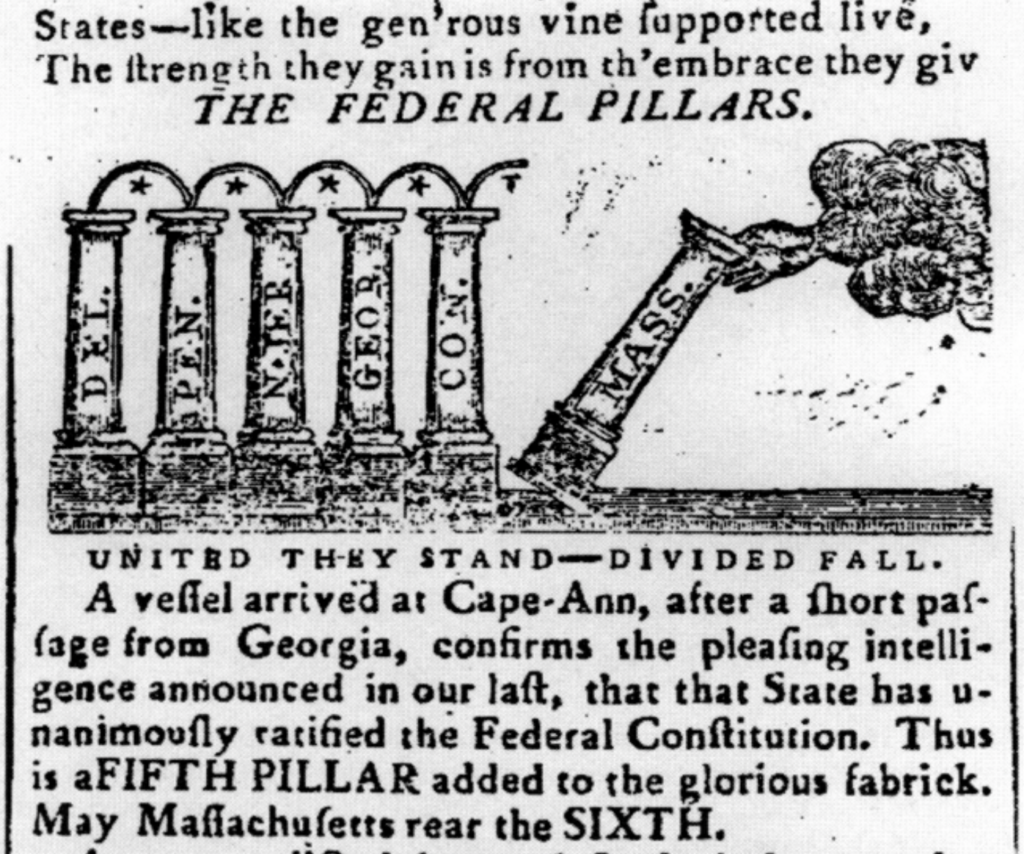

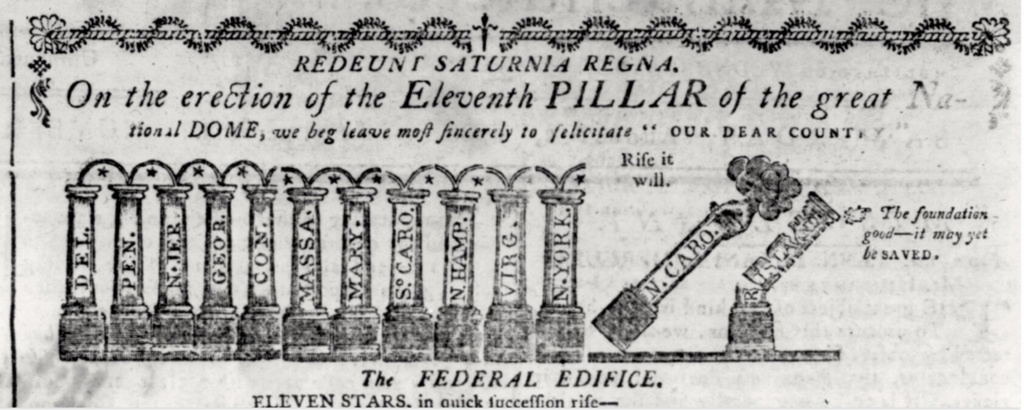

Ratification Timeline (CSAC / U Wisconsin)

| State | Convention | Vote on Ratification | Vote | Map | Introduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delaware | 3–7 December 1787 | 7 December 1787 | 30-0 | Map | Essay |

| Pennsylvania | 20 November–15 December 1787 | 12 December 1787 | 46-23 | Map | Essay |

| New Jersey | 11–20 December 1787 | 18 December 1787 | 38-0 | Map | Essay |

| Georgia | 25 December 1787–5 January 1788 | 31 December 1787 | 26-0 | Map | Essay |

| Connecticut | 3–9 January 1788 | 9 January 1788 | 128-40 | Map | Essay |

| Massachusetts | 9 January–7 February 1788 | 6 February 1788 | 187-168 | Map | Essay |

| Maryland | 21–29 April 1788 | 26 April 1788 | 63-11 | Map | Essay |

| South Carolina | 12–24 May 1788 | 23 May 1788 | 149-73 | Map | Essay |

| New Hampshire | 13–22 February 1788 (1st session) 18–21 June 1788 (2nd session) |

21 June 1788 | 57-47 | Map | Essay |

| Virginia | 2–27 June 1788 | 25 June 1788 | 89-79 | Map | Essay |

| New York | 17 June–26 July 1788 | 26 July 1788 | 30-27 | Map | Essay |

| North Carolina | 21 July–4 August 1788 (1st convention) 16–23 November 1789 (2nd convention) |

2 August 1788 21 November 1789 |

75-193 194-77 |

Maps | Essay |

| Rhode Island | 1–6 March 1790 (1st session) 24–29 May 1790 (2nd session) |

29 May 1790 | 34-32 | Map | Essay |

| Vermont | 6-10 January 1791 | 10 January 1791 | 105-4 | Map | Essay |

Federalist No. 10 (Madison // Nov. 23, 1787)

Liberty is to faction what air is to fire…

Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.

The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man; and we see them everywhere brought into different degrees of activity, according to the different circumstances of civil society. A zeal for different opinions concerning religion, concerning government, and many other points, as well of speculation as of practice; an attachment to different leaders ambitiously contending for pre-eminence and power; or to persons of other descriptions whose fortunes have been interesting to the human passions, have, in turn, divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to co-operate for their common good.

The smaller the society, the fewer probably will be the distinct parties and interests composing it; the fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of individuals composing a majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed, the more easily will they concert and execute their plans of oppression. Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other.

Federalist No. 51 (Madison // February 8, 1788)

Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.

But the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others. The provision for defense must in this, as in all other cases, be made commensurate to the danger of attack. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.

Federalist No. 70 (Hamilton // March 18, 1788)

Energy in the Executive is a leading character in the definition of good government.

THERE is an idea, which is not without its advocates, that a vigorous Executive is inconsistent with the genius of republican government. The enlightened well-wishers to this species of government must at least hope that the supposition is destitute of foundation; since they can never admit its truth, without at the same time admitting the condemnation of their own principles. Energy in the Executive is a leading character in the definition of good government. It is essential to the protection of the community against foreign attacks; it is not less essential to the steady administration of the laws; to the protection of property against those irregular and high-handed combinations which sometimes interrupt the ordinary course of justice; to the security of liberty against the enterprises and assaults of ambition, of faction, and of anarchy. Every man the least conversant in Roman story, knows how often that republic was obliged to take refuge in the absolute power of a single man, under the formidable title of Dictator, as well against the intrigues of ambitious individuals who aspired to the tyranny, and the seditions of whole classes of the community whose conduct threatened the existence of all government, as against the invasions of external enemies who menaced the conquest and destruction of Rome.

There can be no need, however, to multiply arguments or examples on this head. A feeble Executive implies a feeble execution of the government. A feeble execution is but another phrase for a bad execution; and a government ill executed, whatever it may be in theory, must be, in practice, a bad government.

Federalist No. 78 (Hamilton // May 27, 1788)

A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law.

According to the plan of the convention, all judges who may be appointed by the United States are to hold their offices DURING GOOD BEHAVIOR; which is conformable to the most approved of the State constitutions and among the rest, to that of this State. Its propriety having been drawn into question by the adversaries of that plan, is no light symptom of the rage for objection, which disorders their imaginations and judgments. The standard of good behavior for the continuance in office of the judicial magistracy, is certainly one of the most valuable of the modern improvements in the practice of government. In a monarchy it is an excellent barrier to the despotism of the prince; in a republic it is a no less excellent barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body. And it is the best expedient which can be devised in any government, to secure a steady, upright, and impartial administration of the laws.

There is no position which depends on clearer principles, than that every act of a delegated authority, contrary to the tenor of the commission under which it is exercised, is void. No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the Constitution, can be valid. To deny this, would be to affirm, that the deputy is greater than his principal; that the servant is above his master; that the representatives of the people are superior to the people themselves; that men acting by virtue of powers, may do not only what their powers do not authorize, but what they forbid. If it be said that the legislative body are themselves the constitutional judges of their own powers, and that the construction they put upon them is conclusive upon the other departments, it may be answered, that this cannot be the natural presumption, where it is not to be collected from any particular provisions in the Constitution. It is not otherwise to be supposed, that the Constitution could intend to enable the representatives of the people to substitute their WILL to that of their constituents. It is far more rational to suppose, that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority. The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body.