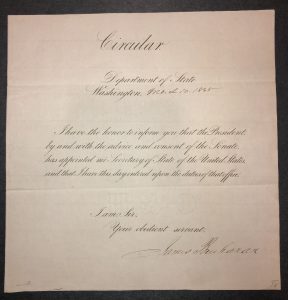

James Buchanan was born on April 23rd, 1791 in Cove Gap, Pennsylvania to a well-off family[1]. Buchanan graduated from Dickinson College in 1809, though he claimed little attachment to the school as “his life [there] had not been happy.”[2] James Buchanan was expelled in 1808 for poor behavior, but re-enrolled after a plea to his school minister.[3] Despite his performance as an undergraduate student, Buchanan continued on to study law in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.[4] As his law career grew and he gained recognition, Buchanan was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives.[5] Buchanan took on a plethora of different roles throughout his life, including Minister to Russia, US senator, Minister to Great Britain, and the 15th President of the United States from 1857-61. Additionally, Buchanan served as the Secretary of the United States Department of State.

James Buchanan was appointed Secretary of State under President James K. Polk in 1845.[6] Polk

appointed Buchanan as Secretary of State, in part, because of his constant interest and talent in connection to the foreign relations of the United States.[7] With this appointment to office, Buchanan was able to act upon his expansionist viewpoints. Under Polk and Buchanan, the territory of the United States significantly increased as a result of the Oregon Treaty and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This post will focus on the Oregon Treaty and Buchanan’s success in expanding US territory into the northwest.

The Oregon Treaty of 1846 was the result of one of the most important diplomatic disputes in the first half of the 19th century.[8] The disputed territory of Oregon was the focus of those who believed in was the United States’ duty and right to spread its control, laws, and liberties across North America. This rationale for expansion stemmed from the idea of Manifest Destiny, as well as the thought that US morals and way of life brought civilization to the territories it controlled. Originally, Spain, Great Britain, Russia and the United States claimed control of the Oregon territory. However, due to the decline in power and strength which characterized the Spanish empire at this time, the Spanish ceded control to the United States in the Transcontinental Treaty of 1819.[9] Following this, Russia attempted to secure ownership of the territory, but faced pushback in 1823 when President Monroe notified Russia that the US did not accept their claim.[10] The border dispute grew throughout the years as American westward expansion further pushed into the territory. James Buchanan decided that American border expansion westward and into Oregon was the best option as not many people had explored that area of what was, at the time, Canada. Initially Buchanan wanted to settle an agreement with the British at the 49th parallel, however President Polk insisted on America’s right to controlling even more land.[11] Democrats, supporting further expansion to spread American territory to cover westward settlers, started to coin the slogan “54°40’ or fight”.[12] These boundaries aimed to include the land north of Fort Simpson in British-controlled Canadian territory.[13] With the support of his constituents, Buchanan agreed to negotiate for further control stating, “war before dishonor is a maxim deeply engraved upon the hearts of the American people.”[14] This quote illustrates Buchanan’s idea to go to war with the British, had they disagreed with American terms and boundaries. However, President Polk changed his mind and once again decided it was in America’s best interest to settle with the British at the 49th parallel.[15]

Click to view the original Oregon Treaty

The final settlement came with the signing of the Oregon Treaty on June 15th, 1846 in Washington, DC. The first article states: “from the point of the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude… the line of boundary between the territories of the United States and those of her Britannic Majesty shall be continued westward along the said forty-ninth parallel of north latitude.”[16] Additionally, the treaty guarantees free passage of the channel and Fuca’s straits to both the United States and Great Britain.

James Buchanan was a controversial president of the United States, but his time as Secretary of State showed multiple successes. He was a successful diplomat as he had experience working as ministers abroad in Russia and Great Britain. This time abroad taught him the functions of British colonialism and gave him an informed perspective into the possibility of future British involvement in areas of disputed boundaries. Specifically, Buchanan was able to use his experience abroad to identify the possible threat that British control could pose in relation to American dealings in Oregon, Texas, and Mexico.[17] Positive and effective diplomacy greatly depends on experience and communication abroad, which is what contributed to the success of James Buchanan’s tenure as Secretary of State.

[1] “James Buchanan.” National Archives and Records Administration. [web]

[2] George Leakin Sioussat, “James Buchanan,” in The American Secretaries of State and Their Diplomacy, ed. Samuel Flagg Bemis (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928), vol. 5, 241.

[3] “James Buchanan (1791-1868).” Dickinson College Archives, 2005. [web]

[4] ibid.

[5] ibid.

[6] George Leakin Sioussat, “James Buchanan,” in The American Secretaries of State and Their Diplomacy, ed. Samuel Flagg Bemis (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928), vol. 5, 241.

[7] ibid.

[8] “The Oregon Territory, 1846.” U.S. Department of State. [web]

[9] ibid.

[10] ibid.

[11] Jean H. Baker, James Buchanan, (New York: Times Books, 2004), 40.

[12] ibid.

[13] ibid.

[14] Jean H. Baker, James Buchanan, (New York: Times Books, 2004), 41.

[15] ibid.

[16] Oregon Treaty, 5 August 1846, ARC 299808, National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives at Washington, DC, United States. [web]

[17] Jean H. Baker, James Buchanan, (New York: Times Books, 2004), 37.