CHAPTER 14: “A Novel Burden Far From Our Shores”: Truman, the Cold War, and the Revolution in U.S. Foreign Policy, 1945-1953

- 1945 // Ministers Meeting

- 1946 // Stalin’s Election Speech

- 1946 // Kennan’s Long Telegram

- 1946 // Iron Curtain Speech

- 1946 // Philippine Independence

- 1946 // Iranian Crisis

- 1946 // Turkish Crisis

- 1947 // Truman Doctrine

- 1947 // National Security Act

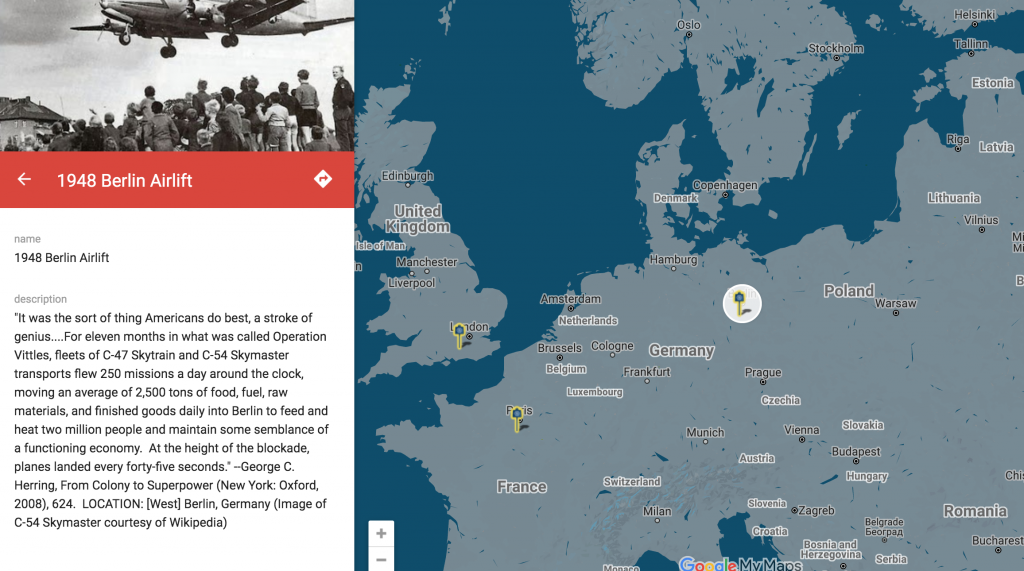

- 1948 // Berlin Airlift

- 1948 // Marshall Plan

- 1949 // NATO

- 1949 // Communist China

- 1950 // NSC-68

- 1950-53 // Korean War

From Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech in Fulton, Missouri (1946)

Churchill’s stern 1946 warning about the Soviets highlighted a growing tension in superpower relations, a period that columnist Walter Lippmann described memorably as “The Cold War.” The US policy toward the Soviet Union which subsequently defined this Cold War period has come to be known as containment. State Department official George Kennan helped develop this containment doctrine, principally through two powerful documents, the so-called “Long Telegram,” and an anonymous article for the journal Foreign Affairs, titled, “The Sources of Soviet Conduct.” Here is an excerpt from the now-famous 1947 article:

These considerations make Soviet diplomacy at once easier and more difficult to deal with than the diplomacy of individual aggressive leaders like Napoleon and Hitler. On the one hand it is more sensitive to contrary force, more ready to yield on individual sectors of the diplomatic front when that force is felt to be too strong, and thus more rational in the logic and rhetoric of power. On the other hand it cannot be easily defeated or discouraged by a single victory on the part of its opponents….In these circumstances it is clear that the main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.

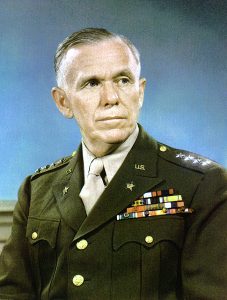

KEY PLAYERS

George Kennan (1904-2005)

“The namesake of a distant relative who in the late nineteenth century had documented for enthralled US. audiences the horrors of the Siberian exile system, the younger [George] Kennan was one of a handful of men trained after World War I as experts on Bolshevik Russia. Conservative in his tastes and politics and scholarly in demeanor, he developed a deep admiration for traditional Russian literature and culture and, from service in the Moscow embassy after 1933, an even deeper antipathy for the Soviet state. Frustrated during the war when the Roosevelt administration ignored his cautionary recommendations, he eagerly responded when Truman’s State Department requested his views. ‘They had asked for it,’ he later wrote. ‘Now, by God, they would get it.’ In highly alarmist tones, he delivered over the wires [in early 1946] a lecture on Soviet behavior that decisively influenced the origins and nature of the Cold War.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 604)

“The namesake of a distant relative who in the late nineteenth century had documented for enthralled US. audiences the horrors of the Siberian exile system, the younger [George] Kennan was one of a handful of men trained after World War I as experts on Bolshevik Russia. Conservative in his tastes and politics and scholarly in demeanor, he developed a deep admiration for traditional Russian literature and culture and, from service in the Moscow embassy after 1933, an even deeper antipathy for the Soviet state. Frustrated during the war when the Roosevelt administration ignored his cautionary recommendations, he eagerly responded when Truman’s State Department requested his views. ‘They had asked for it,’ he later wrote. ‘Now, by God, they would get it.’ In highly alarmist tones, he delivered over the wires [in early 1946] a lecture on Soviet behavior that decisively influenced the origins and nature of the Cold War.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 604)

VS.

Henry Wallace (1888-1965)

“The firing of dissident Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace just two weeks before delivery of the Clifford-Elsey report solidified the Cold War consensus. For years Wallace had been the torchbearer for American liberals. After most other New Dealers had left office or jumped aboard the Cold War bandwagon, he kept the faith, privately and publicly pleading for cooperation with the Soviet Union and questioning the get-tough approach….Like Kennan, Wallace harked back to Russian history to explain Soviet insecurity, but he drew very different conclusions, warning of their sensitivity to U.S. moves they viewed as provocative. He sharply criticized U.S. atomic policy and the get-tough approach. “The tougher we get, the tougher the Russians will get,” he averred.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 610-11)

“The firing of dissident Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace just two weeks before delivery of the Clifford-Elsey report solidified the Cold War consensus. For years Wallace had been the torchbearer for American liberals. After most other New Dealers had left office or jumped aboard the Cold War bandwagon, he kept the faith, privately and publicly pleading for cooperation with the Soviet Union and questioning the get-tough approach….Like Kennan, Wallace harked back to Russian history to explain Soviet insecurity, but he drew very different conclusions, warning of their sensitivity to U.S. moves they viewed as provocative. He sharply criticized U.S. atomic policy and the get-tough approach. “The tougher we get, the tougher the Russians will get,” he averred.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 610-11)

KEY TERMS: Long Telegram (1946) // Berlin Blockade (1948-49)

Long Telegram (1946)

“Less than two weeks later [in February 1946], [George] Kennan unleashed on the State Department his famous and influential “Long Telegram,” an eight-thousand-word missive that assessed Soviet policies in the most gloomy and ominous fashion. The namesake of a distant relative who in the late nineteenth century had documented for enthralled U.S. audiences the horrors of the Siberian exile system, the younger Kennan was one of a handful of men trained after World War I as experts on Bolshevik Russia. Conservative in his tastes and politics and scholarly in demeanor, he developed a deep admiration for traditional Russian literature and culture and, from service in the Moscow embassy after 1933, an even deeper antipathy for the Soviet state. Frustrated during the war when the Roosevelt administration ignored his cautionary recommendations, he eagerly responded when Truman’s State Department requested his views. ‘They had asked for it,’ he later wrote. ‘Now, by God, they would get it.’ In highly alarmist tones, he delivered over the wires a lecture on Soviet behavior that decisively influenced the origin and nature of the Cold War.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, p. 604

Discussion Questions

- George Kennan was one of the most influential diplomats in American history and yet never rose above the status of senior staff at the State Department or later (briefly) as an ambassador overseas. How did Kennan make such an outsized impact on US policymaking?

- How would you describe the US policy of “containment” that emerged after Kennan’s “Long Telegram” in a series of actions and strategic statements during 1946 and 1947?

Berlin Blockade (1948-49)

“The Berlin Blockade [of 1948] posed a major challenge for the United States and its allies. They correctly perceived that Stalin did not want war, but they also recognized that the blockade created a volatile situation in which the slightest misstep could provoke conflict. Certain that the Allied position in West Berlin was militarily indefensible, some U.S. officials pondered the possibility of withdrawal. Others insisted that the United States could not abandon Berlin without undermining the confidence of Western Europeans –a ‘Munich of 1948,’ warned diplomat Robert Murphy. Previously more open to negotiations with the Soviets than Washington, [Gen. Lucius] Clay now urged sending an armed convoy through East Germany to West Berlin. Truman and Marshall chose a less risky course, ‘unprovocative’ but ‘firm’ in Marshall’s words. Drawing on the Army Air Force experience carrying supplies over the Himalayas to China in World War II and a mini-airlift during a Soviet ‘baby-blockade’ of West Berlin just months before, they turned to air power to maintain the Western position in Berlin and sustain its beleaguered people. It was the sort of thing Americans do best, a stroke of genius.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, p. 624

Discussion Questions

- How was the US airlift response to the Berlin Blockade a classic illustration of containment doctrine as it was emerging in the late 1940s?

- What were some of the most significant consequences of the Berlin Blockade?