Did Americans embrace imperialism in the late nineteenth century?

CHAPTER 8: The War of 1898, the New Empire, and the Dawn of the American Century, 1893-1901

“To be sure, the nation broke precedent by acquiring overseas colonies with no intention of admitting them as states. At the same time, in its aims, its methods, and the rhetoric used to justify it, the expansionism of the 1890s followed logically from earlier patterns, built on established precedents, and gave structure to the blueprint drawn up by James G. Blaine in the previous decade.” (Herring, p. 299)

–George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 299.

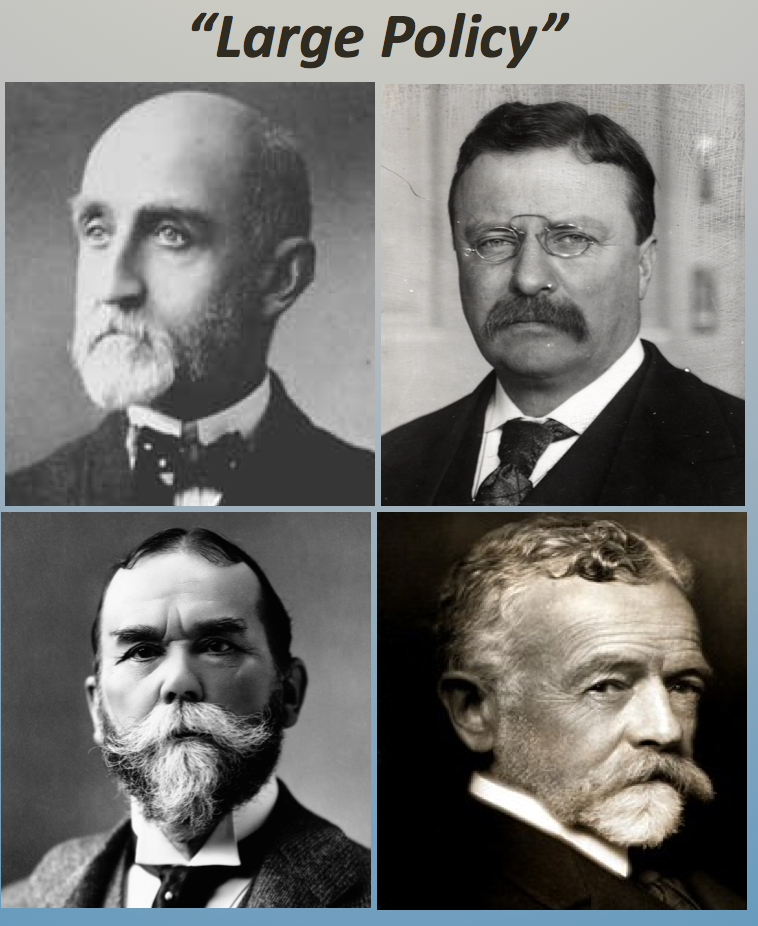

KEY PLAYERS

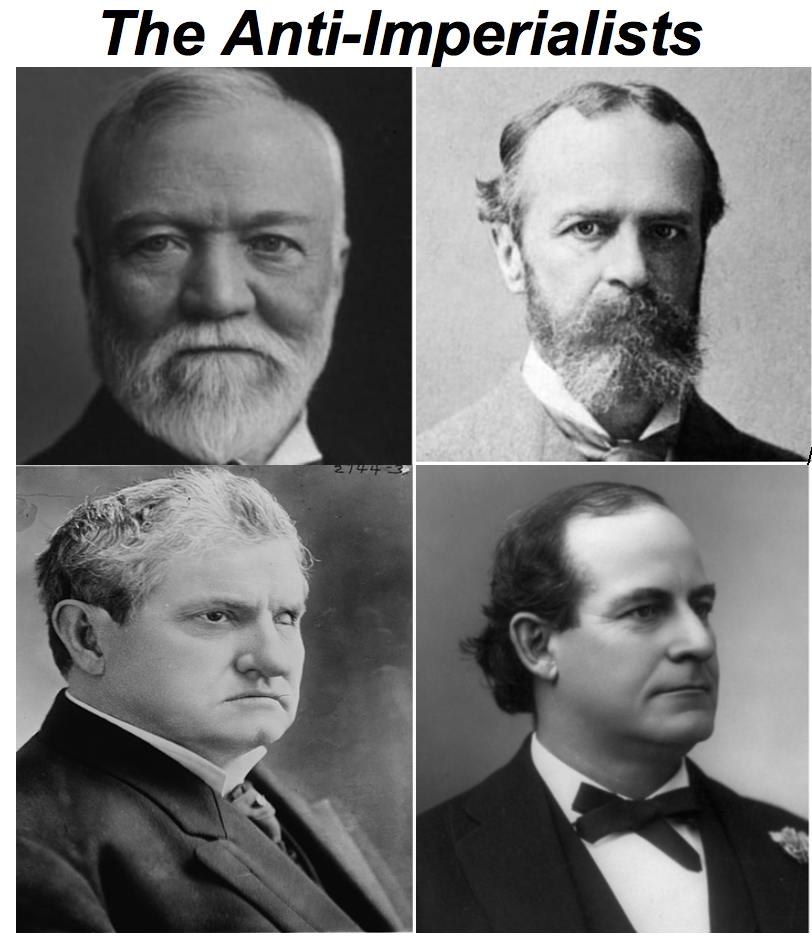

A businessman, a philosopher and two politicians. Can you identify these four leading anti-imperialists?

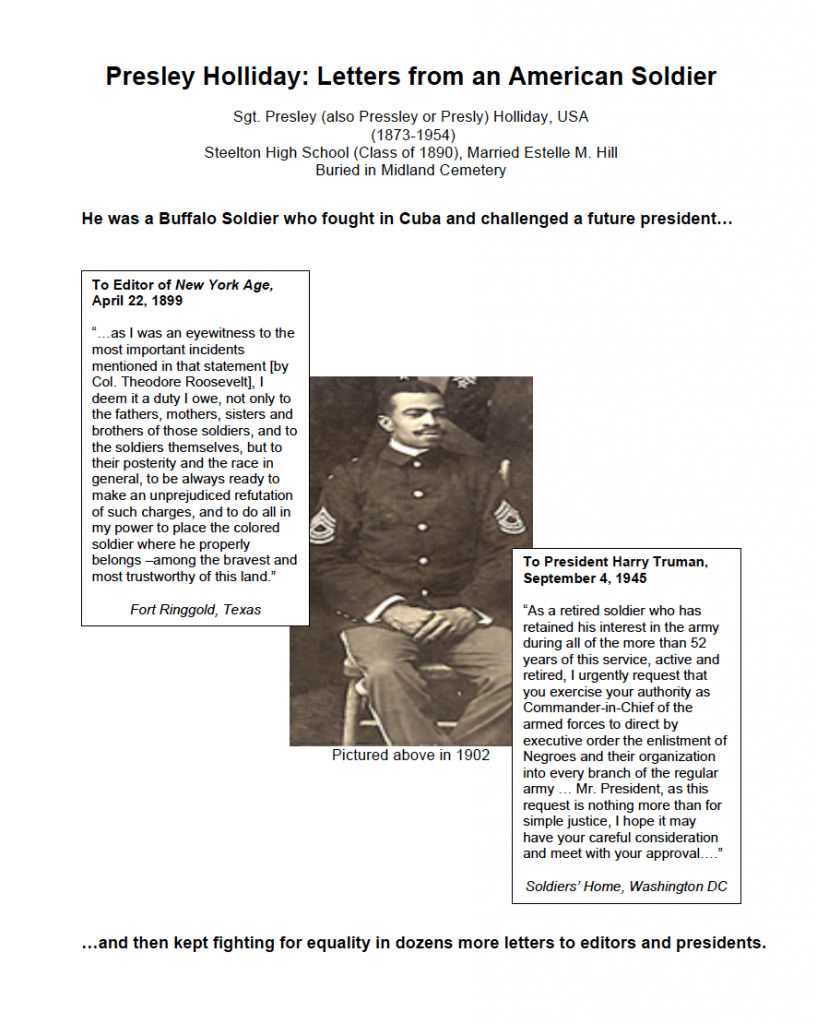

Other Key Players, Witnesses or Examples

- Richard Harding Davis

- Elihu Root

KEY TERMS: War of 1898 // Open Door Notes (1899-1900)

War of 1898

“What was once called the Spanish-American War was the pivotal event of a pivotal decade, bringing the ‘large policy’ to fruition and marking the United States as a world power. Few events in U.S. history have been encrusted in myth and indeed trivialized. The very title is a misnomer, of course, since it omits Cuba and the Philippines, both key players in the conflict. Despite four decades of ‘revisionist’ scholarship, popular writing continues to attribute the war to a sensationalist ‘yellow press,’ which allegedly whipped into martial frenzy an ignorant public that in turn drove weak leaders into an unnecessary war. The war itself has been reduced to comic opera, its consequences dismissed as an aberration. Such treatment undermines the notion of war by design, allowing Americans to cling to the idea of their own noble purposes and sparing them responsibility for a war they came to see as unnecessary and imperialist results they came to regard as unsavory. Such interpretations also ignore the extent to which the war and its consequences represented a logical culmination of major trends in nineteenth-century U.S. foreign policy. It was less a case of the United States coming upon greatness almost inadvertently than of it pursuing its destiny deliberately and purposefully.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, p. 399

Discussion Questions

- Explain the origins of the “large policy” and identify some of the key figures in its formation.

- Would you make any distinctions between the American “large policy” of the 1890s and European-style imperialism of that same era?

Open Door Notes (1899-1900)

“The Open Door Notes have produced as much mythology as anything in the history of U.S. foreign relations. Although he knew better, Hay encouraged and happily accepted popular praise for America’s bold and altruistic defense of China from the rapacious powers. These contemporary accolades evolved into the enduring myth that the United States in a singular act of beneficence at a critical point in China’s history saved it from further plunder by the European powers and Japan. More recently, historians have found in the Open Door Notes a driving force behind much of twentieth-century U.S. foreign policy. Scholar-diplomat George F. Kennan dismissed them as typical of the idealism and legalism that he insisted had characterized the American approach to diplomacy, a meaningless statement in defense of a dubious cause –the independence of China– which had the baneful effect of inflating in the eyes of American s the importance of their interests in China and their ability to dictate events there. Historian William Appleman Williams and the so-called Wisconsin School have portrayed the notes as an aggressive first move to capture the China market that laid the foundation for U.S. policy in much of the world in the twentieth century.” (George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, pp. 333-4)

Discussion Questions

- Herring uses the Open Door episode as way to further delineate major schools of thought about American diplomatic traditions. Earlier in the semester, Walter Russell Mead tried something similar. Can you summarize the different interpretive approaches on your own by this point?

- Among American diplomats and secretaries of state, John Hay usually ranks quite high. How you would characterize his accomplishments? Do recent shifts in American attitudes about imperialism and race diminish the standing of statesmen like Hay (or figures like Theodore Roosevelt) in your eyes?

Student-produced map of the Boxer Rebellion (Julianne Greco)

19th-Century Imperialism –By the Numbers

Between 1870 and 1900, Britain added more than four million square miles to its imperial holdings, France more than three and a half million, and Germany one million. The new rush for empire further destabilized an already unsettled world. –Herring, 268

- During this same period, the US added approximately 500,000 square miles of annexed territory (Guam, Hawaii, Philippines, Puerto Rico); including Alaska (1867) raises the figure above 1 million square miles

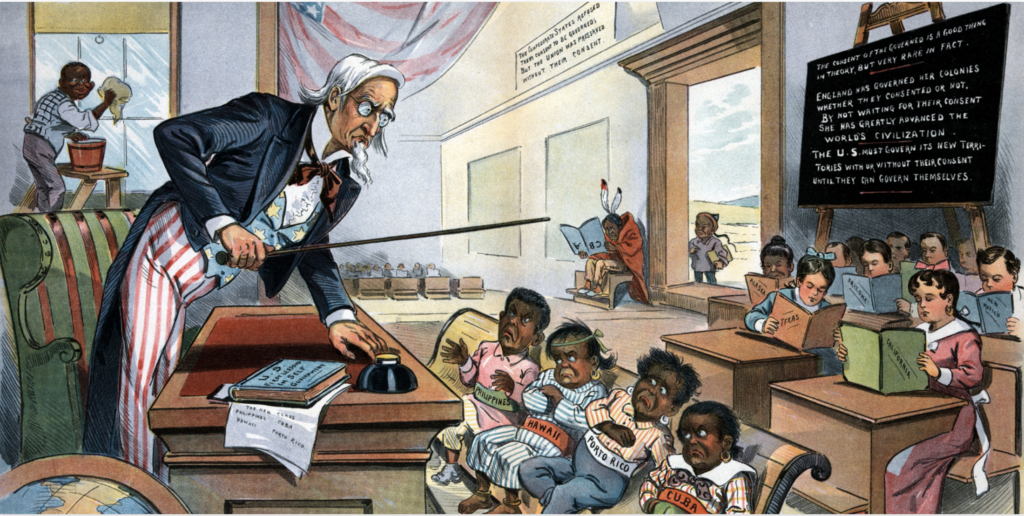

Image Gateway

For more information on this famous 1899 cartoon (“School Begins”) by Louis Dalrymple for Puck magazine, see Brian Shott’s essay in David Prior’s edited collection on Reconstruction and Empire (2022)

Who were the imperial soldiers?

NOTE –Anti-Imperialists above (clockwise from upper left: Andrew Carnegie, William James, William Jennings Bryan, and “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman