By Colin Martin

Throughout history, few pieces of writing have been able to echo through time in such a way as Abraham Lincoln’s 1864 letter to the Widow Bixby. Since 1776, almost every American generation can claim a number of surviving relatives who are able to attest to the pain that accompanies losing a loved one on the battlefield. As the conflict that claimed the highest number of American casualties in the nation’s history, the Civil War often held the mother of a fallen soldier as the most impacted of his kin. While the passage of years helps to heal physical wounds, a mother’s pain caused by losing a child at war will never cease. Bearing this in mind, it is not difficult to understand why President Lincoln might have taken a few moments to pen a message of sympathy to a mother who was dealing with this anguish.

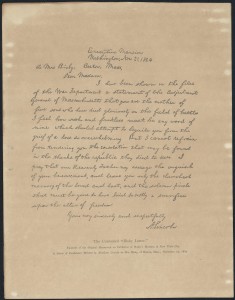

On 24 or 25 November 1864, a note dated Nov. 21 was hand-delivered by General William Schouler to Lydia Bixby, a resident of Boston’s South End [1]. It was a simple letter of condolence. It contained only four sentences, but appeared to have been composed by a man who was familiar with the agony that Lydia was enduring at the time. The letter acknowledged that the author had personally been notified of the deaths of five of Bixby’s sons as they fought for the North. The creator of the memo continued by admitting that, while nothing could be expressed in an attempt to “beguile” Bixby’s agony, her boys had not perished in vain. In closing, the author begged that God ease her sorrow and leave her “only the cherished memory of the loved and lost,” [2] and that Mrs. Bixby may take solace in the fact that her sons had given their lives for the great cause of Freedom. The paper was signed at the bottom, A. LINCOLN.

Facsimile of the original Bixby Letter  Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Abe Lincoln was no stranger when it came to dealing with the loss of children. Within the fifteen years preceding the date on the letter, Lincoln had buried two of his own sons. In 1850, Edward Lincoln died at the early age of three, and Lincoln’s third son, William, succumbed to typhoid fever only twelve years later [3]. In addition to being shaken by the premature deaths of half of his children, Lincoln was also unfortunate enough to experience first-hand how a mother copes with the loss of a child. In February of 1862, he watched as the First Lady slipped into severe depression and “refused to be comforted” after William’s passing [Ibid]. Mary Todd Lincoln dealt with her despair by visiting spiritual mediums in the Washington area, and eventually went so far as to hold séances in the White House in an attempt to reach the spirit of eleven-year-old Willie. Ward Hill Lamon, a friend of Lincoln from his pre-White House days, opined that the president himself did not appear to place much stock in this sort of spiritualism, although he was willing to sacrifice his professional image for the sake of his “gullible wife.” [4]

In addition to dealing with personal tragedy, Lincoln was plagued by the predicament his country was experiencing. By 1864, the weight of the ongoing conflict within the United States had settled heavily on his shoulders. The significant but bloody battlefield advances made by the Union army at ever increasing costs of life, coupled with his standing for reelection in the face of growing public and political opposition, did nothing to lessen the burden carried by the sixteenth president [5]. Despite this overwhelming pressure of national significance, Lincoln remained quite sensitive to the plight of his fellow Americans. One of the president’s most-trusted bodyguards, William Crook (formerly of the Washington Police Force), recalled a scene he witnessed in early 1865 while traveling through the capital city with the president. As the presidential detail coincidentally crossed paths with a wounded and weary Union veteran, recently released from a hospital and still wearing his blue uniform, Lincoln paused to take a seat beside the freshly discharged soldier. Startled, Crook observed as the President of the United States casually made a personal appointment to meet with the man at the White House on the following day in order to cover his concerns [6]. This was the same president who, only months before, had received word from Massachusetts governor John Andrew of a widowed Bostonian whose sons had died while fighting for the Union.

In the midst of presiding over a nation at war with itself, Lincoln could not have had the time to individually answer all of the mail addressed to him at the White House. His trusted aide, John Hay, claimed that the president “did not read one [letter] in fifty that he received,” [7] and that Lincoln only personally answered roughly one piece of mail per day. Given these circumstances, many historians, professional and amateur alike, consider it very likely that John Hay was the actual source of the letter sent to Lydia Bixby. It is argued that with ample time spent around the president, Hay, a seasoned journalist and “gifted literary mimic,” [8] would have been familiar with the proper vernacular to employ in a letter of sympathy. According to Michael Burlingame’s research, while combing through several of Hay’s writings, the term beguile frequently appears in various forms, as Hay describes his dealings with Democrats, writes to possible love interests, and depicts the dietary habits of the infantry [Ibid]. Hay also reputedly claimed to have written the letter to the widow at various times throughout his life, as was put forth by his personal secretary, Spencer Eddy. Additionally, other contemporaries, including Nicholas Murray Butler of Columbia University, admitted to having learned this from sources close to Hay [Ibid]. To the contrary, however: F. Lauriston Bullard, Pulitzer Prize recipient and advocate for Lincoln’s authorship of the letter, states that although he seemed to swagger before his peers over the matter, oddly, Hay never told his own family that he wrote the famous Bixby letter [9]. Another Lincoln historian agrees with Bullard. William E. Barton personally interviewed Hays’ children and reported that none of them had ever heard their father speak of his involvement with the Bixby letter [Ibid].

In an article written for the American Heritage Society in 2006, Jason Emerson revisits some long-forgotten correspondence of Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s oldest son. As the Bixby letter controversy exploded on the media scene in the early twentieth century, many northeastern newspapers approached Lincoln about the authenticity of his father’s letter. Robert Lincoln recounted to an Abraham Lincoln biographer, Isaac Markens, that while the president often kept hand-copied versions of mail sent on his behalf, he usually never retained copies of letters he personally composed [10]. As there is no known authentic copy of the original Bixby letter, this last account by Robert Lincoln lends credence to the argument for Lincoln’s authorship. Robert Lincoln recorded having asked his good friend, Secretary of State John Hay, whether he knew of the origins of the famous note. Hay had denied having any uncommon knowledge of the letter or its authorship . This confession of ignorance by Abraham Lincoln’s secretary to the son of the man he served effectively undermines Hay’s previous claims as the letter’s author [Ibid]. In arguing for Lincoln’s case, the final blow often delivered to Hay proponents is the historical fact that a state governor requested the President to write to the mother of the Bixby boys after word of their deaths. Considering Lincoln’s familiarity with the loss of children and the anguish endured by a grieving mother, his willingness to engage the average American citizen, and his “deep respect for life in general,” [Ibid] it is probable that Abraham Lincoln was the actual author of his letter.

An examination of the original letter to the Widow Bixby could very possibly clear up any uncertainty as to the true source of words. Unfortunately for posterity, such an examination will most likely never be possible. According to her grandchildren, not long after Mrs. Bixby took possession of the letter from General Schouler, she destroyed it. History has come to identify Lydia Bixby as a cheat, the supposed manager of “a house of ill repute,” and as a copperhead [11]. In addition to allegations of her Confederate sympathizing, Lydia’s reputation was further tarnished when it was eventually uncovered that three of her sons were not listed as war fatalities. Two of her sons were reported as deserters, one of whom was taken prisoner and later defected to the Confederacy. The remaining surviving Bixby received an honorable discharge at the end of hostilities [12]. These eye-opening developments, dumped on a grieving and sympathetic American public, eventually turned the flow of communal support against Lydia Bixby [13].

The Widow Lydia Bixby  Courtesy of R.J. Norton

Courtesy of R.J. Norton

Regardless of her beliefs or loyalties, Mrs. Bixby remained a mother whose boys were in a combat zone far from home. Due to the complications brought on by unreliable period communication, hasty and limited record keeping, and the overall fog of war, any word received concerning combat casualties could have been considered definite. It remains unknown when Bixby became informed of the reality of her sons’ fates. Lydia should not be blamed for destroying a piece of paper reminding her of the recent, if incorrect, news of the untimely deaths of her children.

There are a number of significant variables contained in the history of Lincoln’s letter to the Widow Bixby, including the widow’s allegiance, the honor of her sons, and even the man who penned the letter. To some, the holes existing in this story may cause the note’s overall effect to be diminished. On the other hand, almost fourscore years after the original manuscript was composed, the author’s words seemed eerily addressed to Tom and Alleta Sullivan of Waterloo, Iowa. It was January of 1943, and they had just been informed of the fates of their sons. All five Sullivan brothers perished in the sinking of the U.S.S. Juneau [14]. In spite of the controversy and scholarly debate that has erupted over the topic of Lincoln’s note, what is important to realize about the Bixby letter, and continues to remain relevant to this day, is that for more than one hundred and fifty years, this beautifully crafted message, comprised of only four carefully written sentences, has helped to comfort and console the countless loved ones left behind by fallen servicemen and women. The man who wrote this letter, in the dark hours of late 1864, must have known that he was writing these words not only for Mrs. Bixby of Boston, but for countless American families of his time and for the relatives of the loved and lost for centuries yet to come.

[1] Judith Giesberg. “In Defense of Boston’s Widow Bixby – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. November 28, 2014. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2014/11/28/defense-boston-widow-bixby/1iiMKXLf27SEr8toEhRy8N/story.html.

[2] “Abraham Lincoln to Mrs. Lydia Bixby, November 21, 1864.” Abraham Lincoln to Mrs. Lydia Bixby, November 21, 1864. July 2, 2013. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/40453.

[3] “The Death and Funeral of Willie Lincoln.” The Death and Funeral of Willie Lincoln. January 1, 2015. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/education/williedeath.htm.

[4] Joe Nickell. “Paranormal Lincoln.” The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. June 1, 1999. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.csicop.org/si/show/paranormal_lincoln/.

[5] Nathan Kalmoe. “The Fall of Atlanta and Lincoln’s Reelection: ‘Game-changer’ or Campaign Myth?” Washington Post. September 2, 2014. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2014/09/02/the-fall-of-atlanta-and-lincolns-reelection-game-changer-or-campaign-myth/.

[6] “Employees and Staff: William Henry Crook (1839-1915).” Mr. Lincoln’s White House. January 1, 2015. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/inside.asp?ID=55&subjectID=2.

[7] Jason Emerson. “America’s Most Famous Letter.” American Heritage. March 1, 2006. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.americanheritage.com/content/america’s-most-famous-letter?page=show.

[8] Michael Burlingame. “New Light on the Bixby Letter.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. January 1, 1995. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0016.107/–new-light-on-the-bixby-letter?rgn=main;view=fulltext.

[9] Michael Burlingame. “New Light on the Bixby Letter.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. January 1, 1995. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0016.107/–new-light-on-the-bixby-letter?rgn=main;view=fulltext.

[10] Jason Emerson. “America’s Most Famous Letter.” American Heritage. March 1, 2006. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.americanheritage.com/content/america’s-most-famous-letter?page=show.

[11] Judith Giesberg. “In Defense of Boston’s Widow Bixby – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. November 28, 2014. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2014/11/28/defense-boston-widow-bixby/1iiMKXLf27SEr8toEhRy8N/story.html.

[12] Michael Burlingame. “New Light on the Bixby Letter.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. January 1, 1995. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0016.107/–new-light-on-the-bixby-letter?rgn=main;view=fulltext.

[13] Judith Giesberg. “In Defense of Boston’s Widow Bixby – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. November 28, 2014. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2014/11/28/defense-boston-widow-bixby/1iiMKXLf27SEr8toEhRy8N/story.html.

[14] C. Douglas Sterner. “The Sullivan Brothers.” Home of Heroes. January 1, 2014. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.homeofheroes.com/brotherhood/sullivans.html.

Leave a Reply